Paleontology is in a very real sense the study of origins, of beginnings. Paleontologists study the history of life in order to discover when and how different kinds of living creatures came into being. This month I’d like to discuss two such origin stories. In one case the discovery of the earliest known Pterosaur, those flying reptiles who shared the ancient Earth with the dinosaurs but first some new discoveries about the very beginnings of all the animals on Earth, including you and me!

Today pretty much everybody knows that more than a billion years ago the first living creatures here on Earth were tiny, microscopic single-celled organisms like bacteria and amoeba. Sometime in the distant past some of these single celled creatures learned to live together in groups like those in a sponge. In time, although still many millions of years ago, some of the cells began to perform one function, like digesting food while other cells performed other functions like motion or grabbing food.

Groups like this, where different cells concentrated on different functions to the mutual benefit of all the cells were the first multi-cellular organisms. It is from these creatures that all of the living things see every day have evolved.

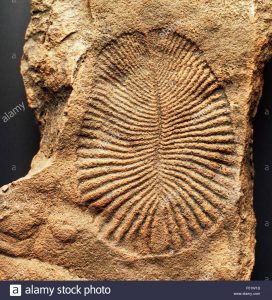

The earliest fossils we have of multi-cellular life are collectively known as the Ediacaran Biota because they were first discovered in the Ediacara region of Australia. Since their first discovery Ediacaran fossils have been found throughout the world and have been dated to between 635 and 541 million years ago.

Because these creatures lived before the evolution of hard parts like bones or bark or shell they do not fossilize well and can be very difficult to study. In some cases paleontologists cannot even tell whether a specimen is a plant or an animal. The images below show several different types of Ediacaran creatures.

A new study published in the journal ‘Paleontology’ seeks to clear away some of the mystery in the Ediacaran Biota and definitively identify the earliest known animal. The study, co-authored by Jennifer F. Hoyal Cuthill of Cambridge University and the Tokyo Institute of Technology, boy I wouldn’t want her commute between jobs, and Jian Han of the Shaanxi Key Laboratory of early life at Northwest University in Xi’an China has provided an evolutionary link between several species in the Ediacaran period to a later species of animal in the Cambrian period (540-485 Million years ago).

The animals in question certainly look more like plants; see artist’s impression below. Known collective as the Petalonamae because of their petal like branches only close examination of the anatomic details in the fossil remains show that the animals are in fact more highly evolved relatives of the sponges. The image below shows a fossil from the Ediacaran period on the right while the fossil that belongs to the Cambrian is on the left.

The results of the study by Doctors Cuthill and Han reveal some of the details of how the animal kingdom itself came into being. A rather important chapter in the history of life.

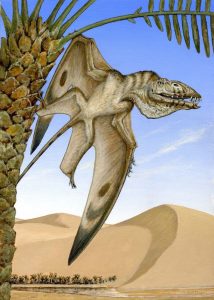

Another chapter in the history of life deals with those flying reptiles, the pterosaurs who filled the sky during the time of the dinosaurs. Now a new species has been identified in fossils unearthed in the state of Utah. At an estimated age of 210 million years old the new pterosaur is some 65 million years older than the previous oldest known flying reptile.

The new species has been named Caelestiventus hanseni by its discoverer Professor Brooks Britt of Brigham Young University. While the specimen was not yet fully grown it already had a wingspan of a meter and a half. The images below show first the almost perfectly preserved skull of C. hanseni and below that an artist’s impression of what the pterosaur might have looked like.

Thanks to the work of dedicated researchers like Doctors Cuthill, Han and Professor Britt we are slowly, bit by bit filling in the missing pages to the story of life on Earth.