Trying to understand the evolution of life on Earth is a bit like trying to figure out the picture on a jigsaw puzzle when you only have a dozen or so of the puzzle’s pieces. Obviously only a very few of the animals who ever lived have made fossils and of the few that have it’s usually only the hard part of the animal that fossilizes, bones and teeth for vertebrates, shells or exoskeletons for invertebrates. It’s a good question, how many species of animals with no hard parts existed in the past about whom we known absolutely nothing?

The first multi-cellular animals, from about 600 million years ago, had no hard parts, and the very few impressions of them that paleontologists have found are so different from today’s species that it is hard to tell just what kind of animal they are. Known as the Ediacaran biota they have been described as quilt like, frond like or even balloon like in structure and whether or not they bare any relationship to the animals of today is a subject of hot debate. See images below.

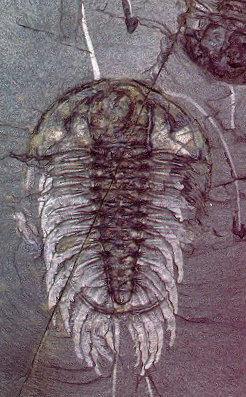

Then, less than 60 million years later during the Cambrian period a very different assemblage of animals appeared as if from nowhere. These animals, best known from the famous Burgess shale fossils, are in most cases recognizable members of the modern major taxonomic groupings. The questions then arise, how did all these different groups arise at the same time, and what is their relation, if any, to the earlier Ediacaran animals.

A recent discovery may provide the first definite link between an Ediacaran creature and a modern group of animals. As is happening more and more in paleontology the discovery wasn’t made by digging up a new fossil in the field but rather by looking at a fossil found years ago with a new instrument.

Tara Selly is a research assistant professor at the Department of Geological Sciences of the University of Missouri who was learning how to examine specimens using the university’s new X-ray microscope. For practice she grabbed a handy fossil, one that happened to come from Nye County in southern Nevada.

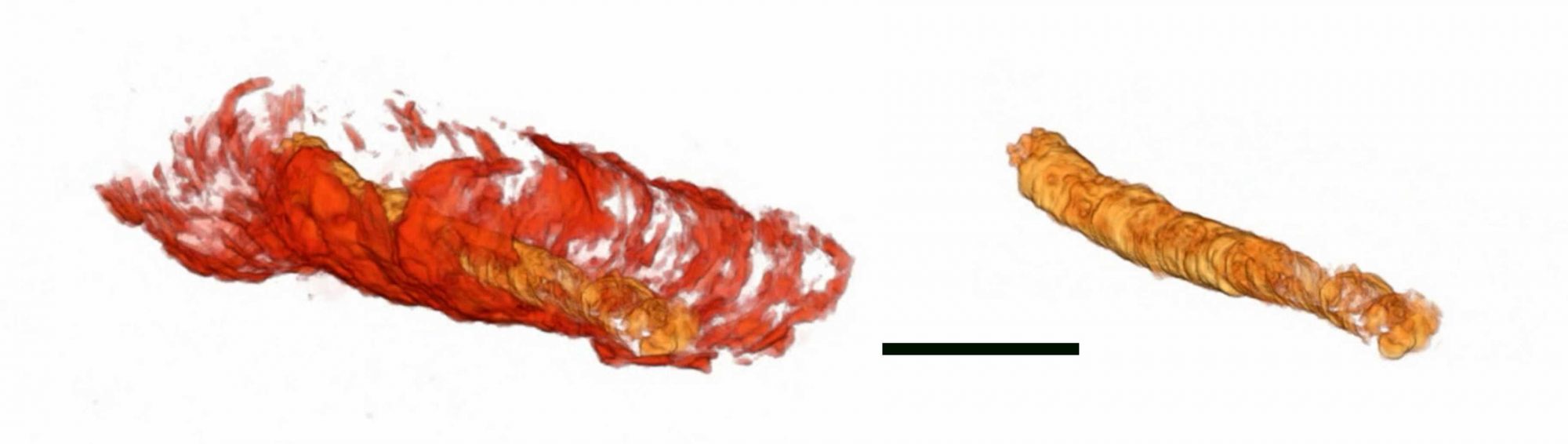

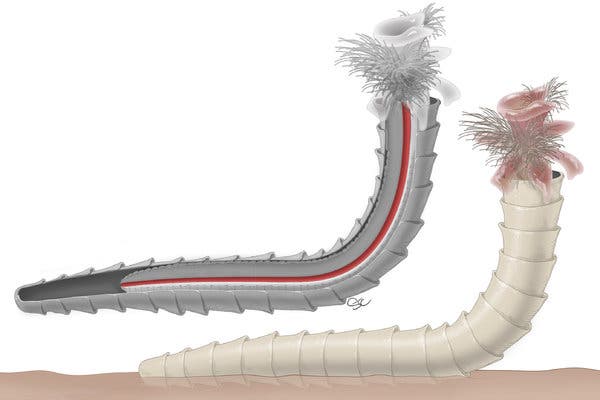

The fossil she chose was of a creature known as a cloudinomorph that dated to the end of the Ediacaran period, about 550 million years ago. Fossil cloudinomorphs are basically little tubes made of the material calcium carbonate and paleontologists have argued for years over whether the animal inside the tube was a relative of a coral medusa (technically an Anthozoan) or a tubeworm (Polychaete).

When Doctor Selly looked at her cloudinomorph with the X-ray microscope she immediately saw a feature that was invisible under normal light, a tube running all the way through the fossil from one end to the other. If, as seemed likely, this tube was the intestine of the cloudinomorph that would immediate eliminate the possibility of the animals being related to a coral. You see corals and jellyfish have only one opening to their digestive system, which serves as both a mouth and an anus.

“A tube would tell us that it’s probably a worm,” according to James Schiffbauer the lead author of the study. “We can now say that their anatomical structure appears much more worm-like than coral-like.” If that is true is would establish the first firm link between an animal from the Ediacaran period and a modern group.

In any case this is also the first evidence of any kind of complex internal structure, an internal organ of some kind inside an animal from the Ediacaran. That alone is important because it tells us that at least some of these early creatures were more than just balloons or quilts of undifferentiated cells. We may only have a few pieces of the jigsaw puzzle of life’s history but perhaps; thanks to Doctors Selly and Schiffbauer we may have just found a very important one.