I have already mentioned the invasive species Spotted Lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula to give them their scientific name, several times in these posts, see post of 8 July 2020. A native of Southeast Asia L delicatula feeds by sucking the sap of fruit trees and vines and is considered a minor agricultural pest in its home region.

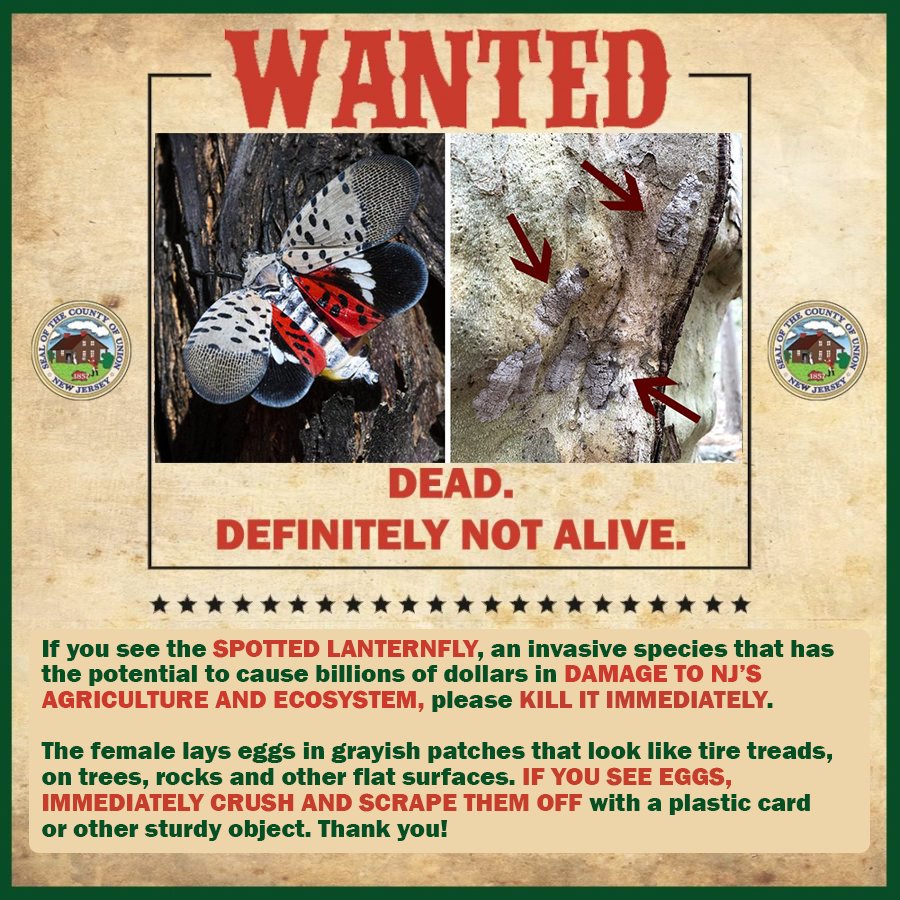

The spotted lanternfly was first discovered in Berks county Pennsylvania in 2014 and in just a few years has spread across Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware and into portions of New York, Connecticut, Maryland, Virginia and Ohio. Wherever they have appeared the pests have caused considerable damage to vineyards and orchards. So great has been the economic damage that State Departments of Agriculture in infested areas have been issuing advisories to kill the lanternflies in any way necessary.

I first saw a few spotted lanternflies in my backyard and neighborhood back in 2019 and at that time was more curious than concerned. Last year in 2020 however there were thousands of them in all over my yard and in various places on every block within walking distance of my home. I killed as many as I could last year but all my efforts hardly made a dent in their numbers. At the time I was convinced that this year could only be worse.

2020 certainly started out bad. The wild grapevines and other bushes in my backyard were heavily infested by early May and all of the spots in my area of Philadelphia where I had seen them last year were also teeming with nymphs. The population explosion didn’t last however, by the middle of June the numbers of spotted lanternflies had definitely declined and now, at the beginning of September the pests have become very difficult to find at all.

Not only that but their behavior has changed as well. Last year, and early this spring in the morning you could see a large number of spotted lanternflies sitting out on leaves in the bright sunshine to warm themselves in the Sun before going back to the branches to feed. Now however, if you want to find any at all you have to look deep in the foliage, several layers of leaves down. L delicatula seems to have become shy as their numbers have declined.

So what’s going on? Something is killing the lanternflies, but what? Is it some disease or fungal infection that is killing them? Or maybe it’s us, is the spraying with insecticide and all the other means we’ve used to control them doing the job?

Nah! The spotted lanternflies I examined lately show no sign of disease, they look as healthy as ever. And some areas that were heavily infested with lanternflies are now virtually clear despite no human doing anything about them.

It looks like what is actually happening is that predators, insect eating birds and other insects have discovered that spotted lanternflies taste good and are worth going after. Scientists at the Academy of Natural Sciences here in Philadelphia think that Preying Mantis’ in particular are feeding on the lanternflies. In fact if you Google images of spotted lanternflies and preying mantis’ you can see a large number of different pictures of a mantis chomping down on a lanternfly. And if predators are the cause of the collapse of lanternfly numbers that would also explain why the remaining flies are now in hiding.

Even if true this doesn’t mean that the problem is over and spotted lanternflies are now under control however. So far it’s only the counties of Berks, Bucks, Montgomery and Philadelphia in Pennsylvania that have seen a major decline in lanternfly numbers. But these are the very counties that have been infested with lanternflies the longest. Other areas, like south Jersey, Maryland, Virginia and New York where the Lanternflies only arrived a year to two ago are still seeing a population explosion. It seems then that it takes the insect eating predators of an area two or three years to recognize the lanternflies as prey and begin eating them in large enough numbers to control the population.

If this theory works out to be true then spotted lanternflies may end up being something like a tsunami, a big wave that causes a lot of damage but eventually recedes. Spotted Lanternflies may show up in small numbers in an area one year, then have a massive population increase for the next 2-3 years only to have predators attack and collapse their numbers afterward.

Other invasive, destructive insects have already followed this scenario. Both Gypsy Moths and Japanese Beetles caused a lot of damage here in the Mid-Atlantic States several decades ago but now their populations are so small that it’s rare to see one. Nature it seems, has a way of regulating itself, of fixing the screw-ups we cause.

There is a limit to even nature’s restorative powers however.