Did you watch it, the first test launch of Space X’s huge Starship launch system that is? Several YouTube channels streamed the entire flight, after all this was the first full test launch of the biggest, most powerful rocket ever built. The test was certainly exciting, but then failed tests are usually more exciting than successful ones.

As I watched that first test on April 20th, it seemed for a while as if everything was going pretty well but then, about a minute into the flight the announcer declared that 28 of Starship’s 33 first stage engines were still firing. That of course made me wonder what had happened to the other five engines. Then, about a minute later it became obvious that the rocket was beginning to tumble out of control and a little more than three minutes into the flight the engineers were forced to self destruct Starship in order to prevent it flying completely out of control and doing any damage to something on the ground.

That didn’t prevent all of the damage at the launch site however. Those five engines that failed first must have exploded right at ignition, based upon all of the debris that was hurled as much as 20 meters away from the launch pad. The pad itself sustained the most damage including a large crater directly beneath it. So extensive is the damage to Starship’s launch facilities that it will take several months to repair them before another Starship test launch can take place. On the other hand, Space X certainly doesn’t want to attempt another launch before they’ve figured out what went wrong on the first one, and that may take longer than repairing the damage that occurred.

Now every engineer knows that failures happen, especially on first tests. I’ve certainly had my share. Space X CEO Elon Musk knows that and did not expect 100% success. Before the test flight he declared that if the giant rocket only ascended past the launch tower he would consider it a partial success. Designing and developing a huge rocket like Starship takes a lot of time and effort and testing, it’s only a matter of time before they get it right.

Much worse is when you’ve done all the design and testing and something goes wrong with the completed product, especially when that product is on its way to the planet Jupiter and there’s absolutely no way to send someone to repair it. That could have been the fate of the European Space Agency’s (ESA’s) JUICE space probe. I discussed the JUICE mission back in February, see my post of 25 February 2023 , as a mission to explore three of Jupiter’s large, Galilean moons in order to determine if there are oceans of liquid water beneath their icy surfaces. The JUpiter ICy moons Explorer or JUICE spaceprobe was launched on April 14th from the ESA’s launch facility in Kourou in French Guiana aboard an Ariane 5 rocket. JUICE’s launch was successful, and within hours the probe was on its way to Jupiter and talking to ground control.

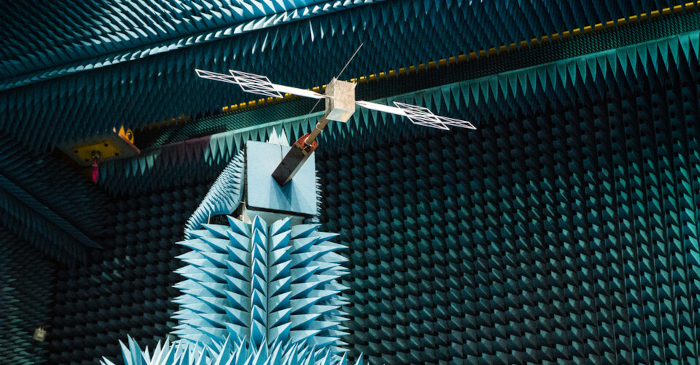

As the probe began to deploy its solar panels and instruments however a problem arose with the antenna for JUICE’s Radar for Icy Moons Exploration (RIME), the instrument that it was hoped would peer beneath the icy surface of the moons to confirm the existence of those oceans. Based on images sent back by the spacecraft the antenna had only unfurled to about one third of its full 16 meter length.

The theory was that a release pin had gotten stuck preventing the antenna from completely deploying. The engineers at the ESA hoped that by using the probe’s course correction engines they may to able to shake the pin loose but they took their time to study the problem. Since JUICE would not reach Jupiter until 2031 the engineers knew that they had plenty of time to consider the problem and come up with a clever trick to fix the antenna.

Turns out they knew what they were doing. After several attempts to fix the problem, each attempt showing a little improvement, the problem was solved when the engineers fired a ‘Non-Explosive Actuator’. The antenna immediately unfurled to it’s proper length.

On the other hand sometimes equipment and systems can be so well designed and built that they far exceed their original design goals. Arguably the two best examples of such extraordinary engineering are the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 space probes.

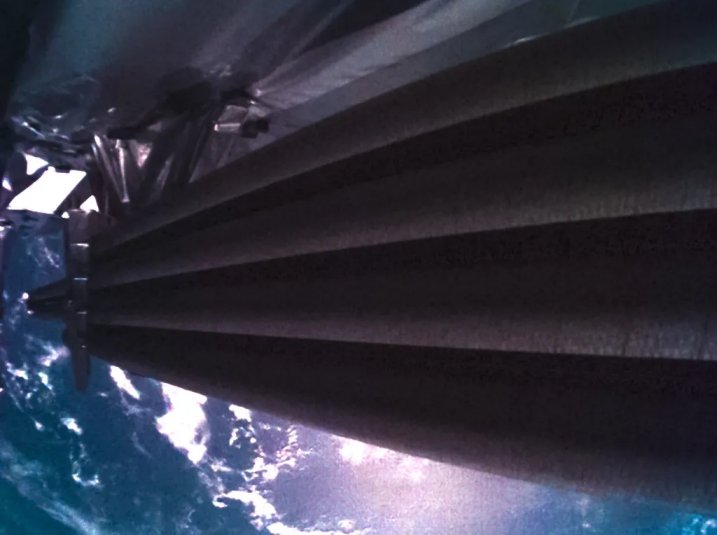

First launched back in 1977, the Voyager spacecraft were designed to conduct flybys of the four gas giant planets in the outer solar system; Voyager 2 is still the only spacecraft to visit Uranus and Neptune. Once their original missions were completed however the two probes just kept working, sending back to Earth measurements of conditions in the outer solar system.

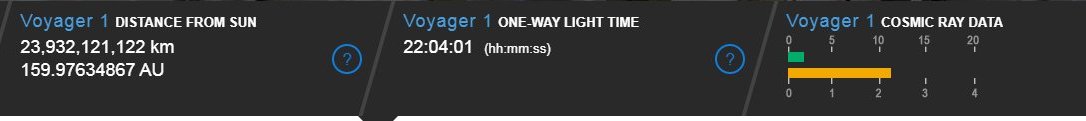

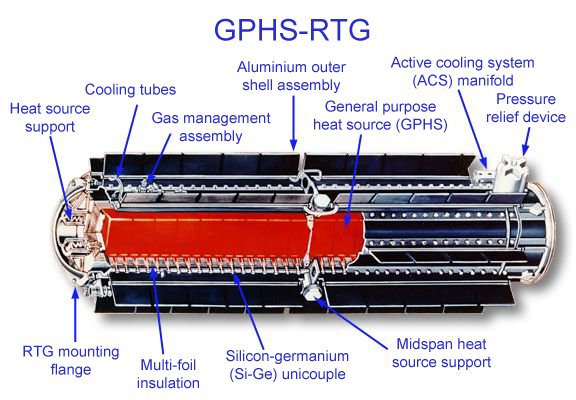

And they are still working, forty-five years after launch both Voyager spacecraft have now entered interstellar space and are still sending back data, the first in situ observations we have of conditions between the stars. Still, nothing lasts forever and slowly but surely the energy provided to each Voyager by its three Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs) is decreasing. Someday the two Voyager probes will no longer have enough energy to radio their observations back to us and they will be lost forever. At launch the RTGs supplied each Voyager with 70 watts of power but the 88 year half life of the radioactive Plutonium has caused that output to decrease by around 30%.

In order to keep each spacecraft functioning for this long the engineers at the Jet Propulsion Labouratory (JPL) have been turning off all unnecessary equipment such as the cameras and heaters to save power. The power loss on Voyager 2 had become so great that it was thought that by the end of the year one of the probe’s five remaining instruments would have to be shut off, with the loss of all that priceless data.

Fortunately those engineers at JPL are some of the best in the world and they came up with a clever idea. The Voyager power system contains a device known as a voltage regulator that’s intended to eliminate spikes and surges in the power coming from the RTGs. With the drop in power from the RTGs there’s now much less danger of that happening and if they shut off the regulator they’d save enough power to keep Voyager 2 running as is with five remaining instruments until at least 2026, almost exactly 50 years after its launch.

The Voyager spacecraft have discovered so much, taught us so much about our solar system and now the galaxy beyond and thanks to the engineers at JPL they can continue to do so, more than 30 years longer than anyone ever expected them to.