If you think about it the science of Paleontology is all about beginnings and endings. New species, new types of life forms evolve, survive for a time and then become extinct. Knowing when a species arises and when it dies out is as important for understanding its place in the history of life as is knowing what kind of creature it was.

In this post I will be discussing two recent studies that illustrate a beginning and an ending not just for a single species but for many thousands of different types of animals. As always I’ll begin with the oldest story and work my way forward in time.

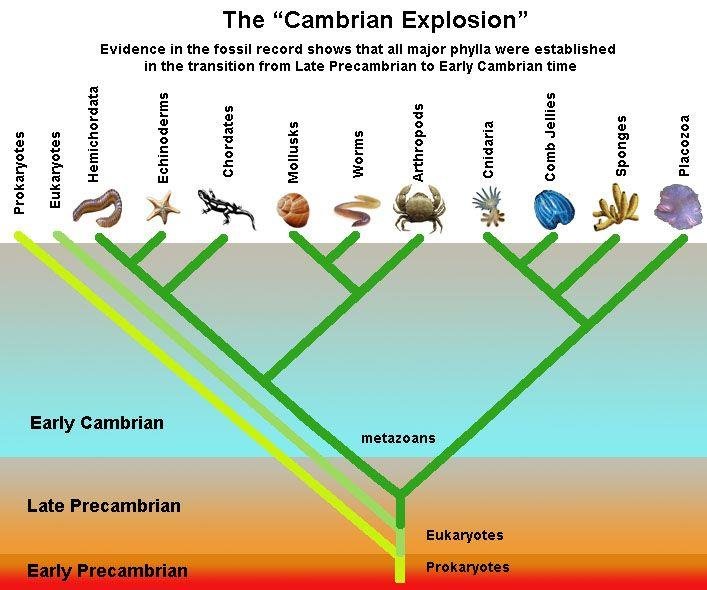

I have several times mentioned the Cambrian Period as being that time in the history of life when animals developed ‘hard parts’, that is shells, exoskeletons or internal skeletons. To paleontologists this advance makes a world of difference because ‘hard parts’ fossilize much more often than does soft tissue. (In my collection I have thousands of shells, a couple hundred exoskeletons along with a handful of bones and teeth but only a very few traces of soft tissue.)

Because of this we have a much better idea of the evolution of life from the Cambrian Period onward than we have for the time before the Cambrian, known as the pre-Cambrian, the time before life had ‘hard parts’. In fact, for nearly a century there was no universally accepted evidence for life of any kind before the ‘Cambrian Explosion’ when dozens of different kinds of animals suddenly appeared. Charles Darwin even considered this abrupt appearance of arthropods, mollusks, brachiopods, worms, sponges and corals to be the greatest problem with his theory of natural selection.

So, if in the Cambrian period we already have arthropods, molluscs, and etc then a lot of evolution must already have happened in the pre-Cambrian and honestly paleontologists have had a very difficult time trying to work it out. Now a recent discovery in the outback of Australia, at the Nilpena Ediacara National Park will hopefully shine some light into the pre-Cambrian darkness.

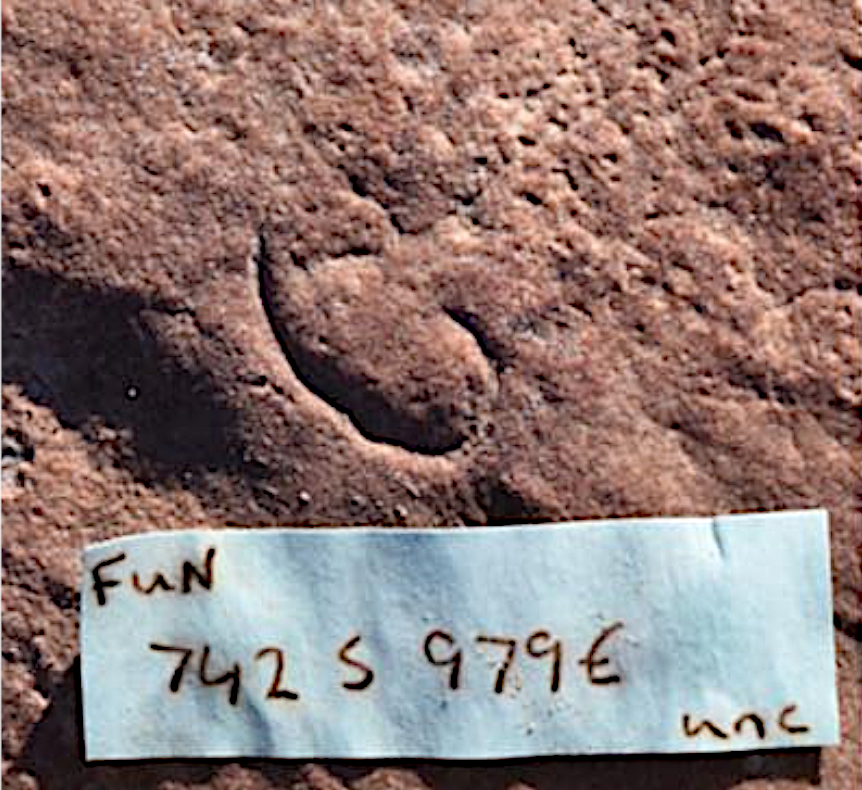

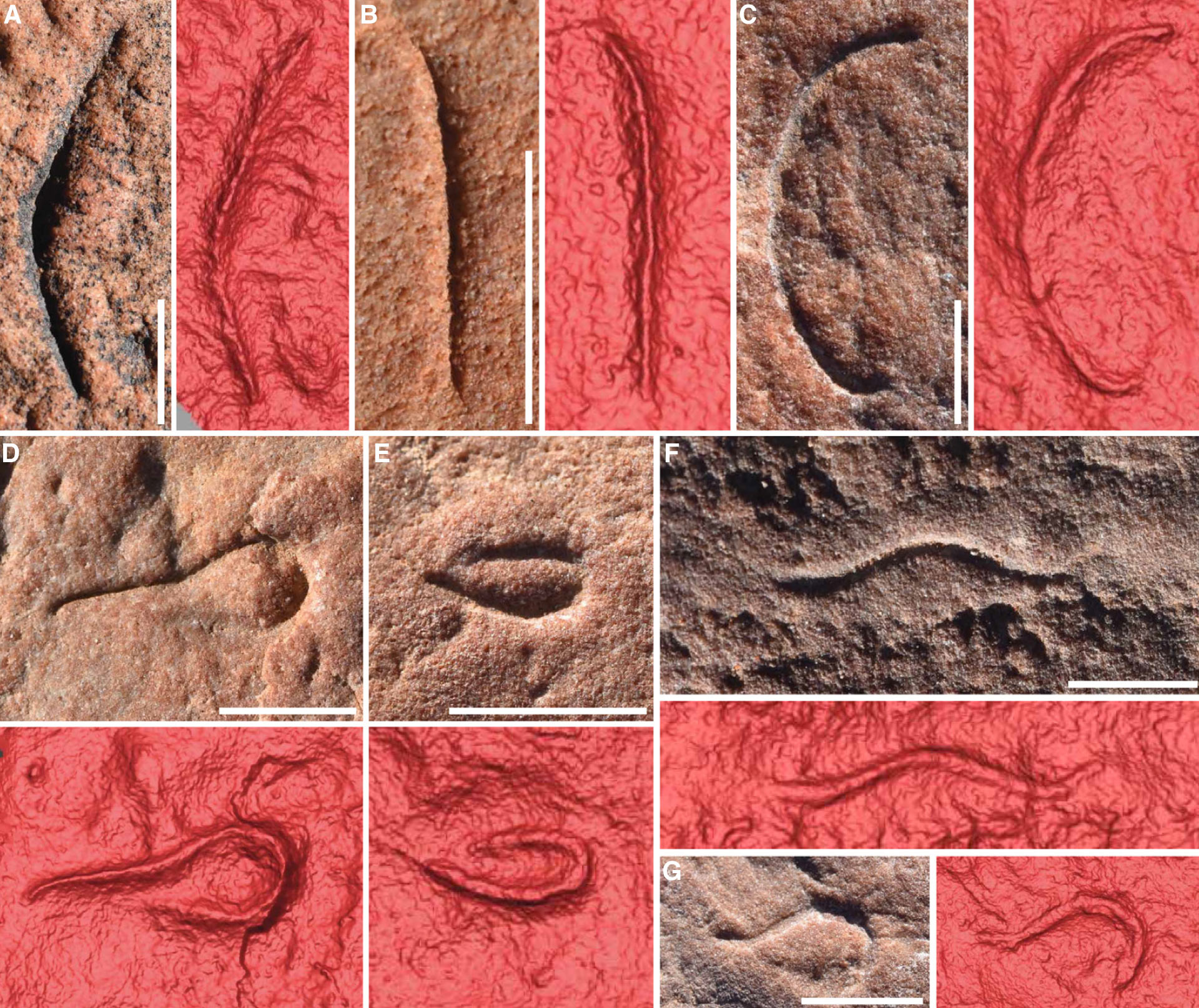

The fossil itself isn’t much to look at, a tiny worm-like animal no more than 2cm in length, see images below. However details of the fossil, which has been given the name Uncus dzaugisi, show that it belongs to the super-phyla known as Ecdysozoan, a grouping of many animal types such as the arthropods, nematodes, tardigradas and priapulida.

What all of these different phyla have in common is a recognizable body length to width ratio that indicates mobility in a definite forward direction, a hard cuticle covering made of organic material, in other words an exo-skeleton not a shell, as well as organs for internal fertilization. Nearly half of all known species, both living and in the fossil record share these qualities. That’s what makes Uncus dzaugisi such an exciting find, it is the earliest fossil specimen ever found that shows clear evidence of all of those characteristics, proving that the Ecdysozoan did exist in pre-Cambrian times.

Australia’s Nilpena Ediacara National Park has long been known as the location where the first pre-Cambrian fossils were discovered. Over one hundred different genera of creatures have been identified there thanks to the fine-grained sandstone that preserves details of the soft tissue. However, few of those animals bear any resemblance to the more familiar Cambrian species that followed. So paleontology has two big questions to answer, how did the creatures of the Cambrian evolve in the pre-Cambrian, and what happened to the majority of the creatures that lived during the pre-Cambrian. The answers to those questions can only be found by discovering more fossils like Uncus dzaugisi.

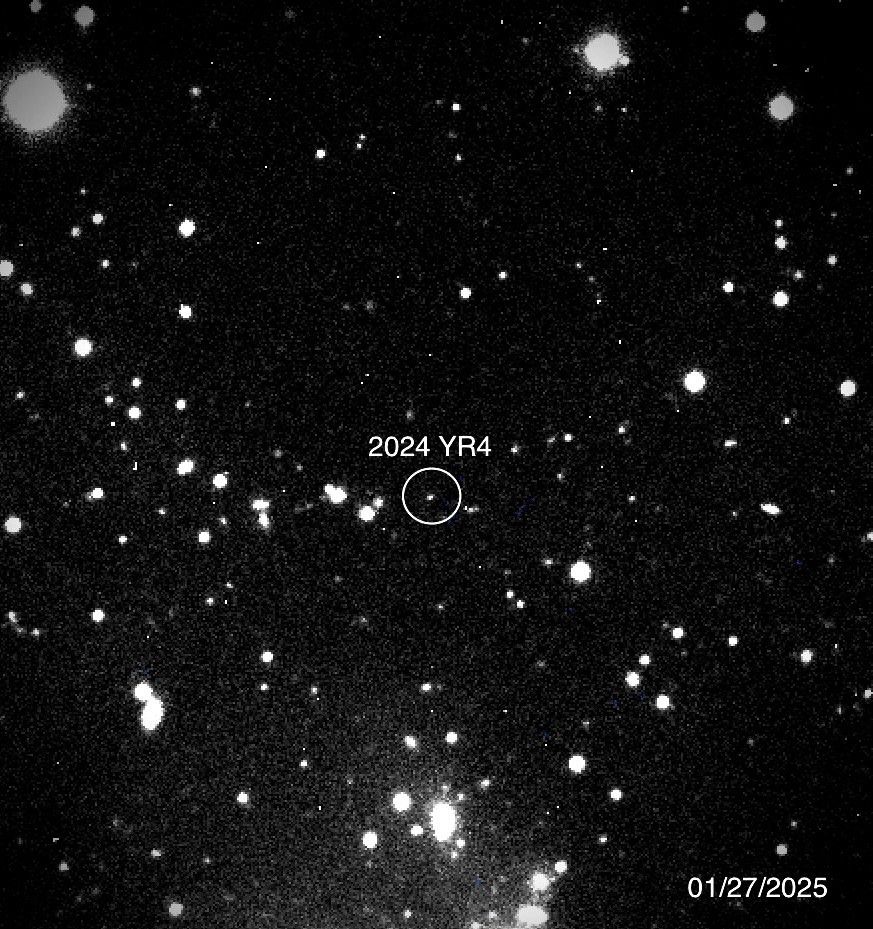

If Uncus dzaugisi represents the beginning for of the many species of the Ecdysozoan then the extinction of the dinosaurs must represent the best-known ending for thousands of species. For the last fifty years the prevailing theory about what caused the mass extinction 66 million years ago has been that an asteroid some ten kilometers in diameter struck our planet in the Yucatan peninsula. That collision not only killed every living thing for thousands of kilometers but it also ejected billions of Tonnes of material into the atmosphere blocking out the Sun’s light for several years and spreading the destruction worldwide. The evidence for this cosmic catastrophe can be found as a thin layer of debris spread around the world.

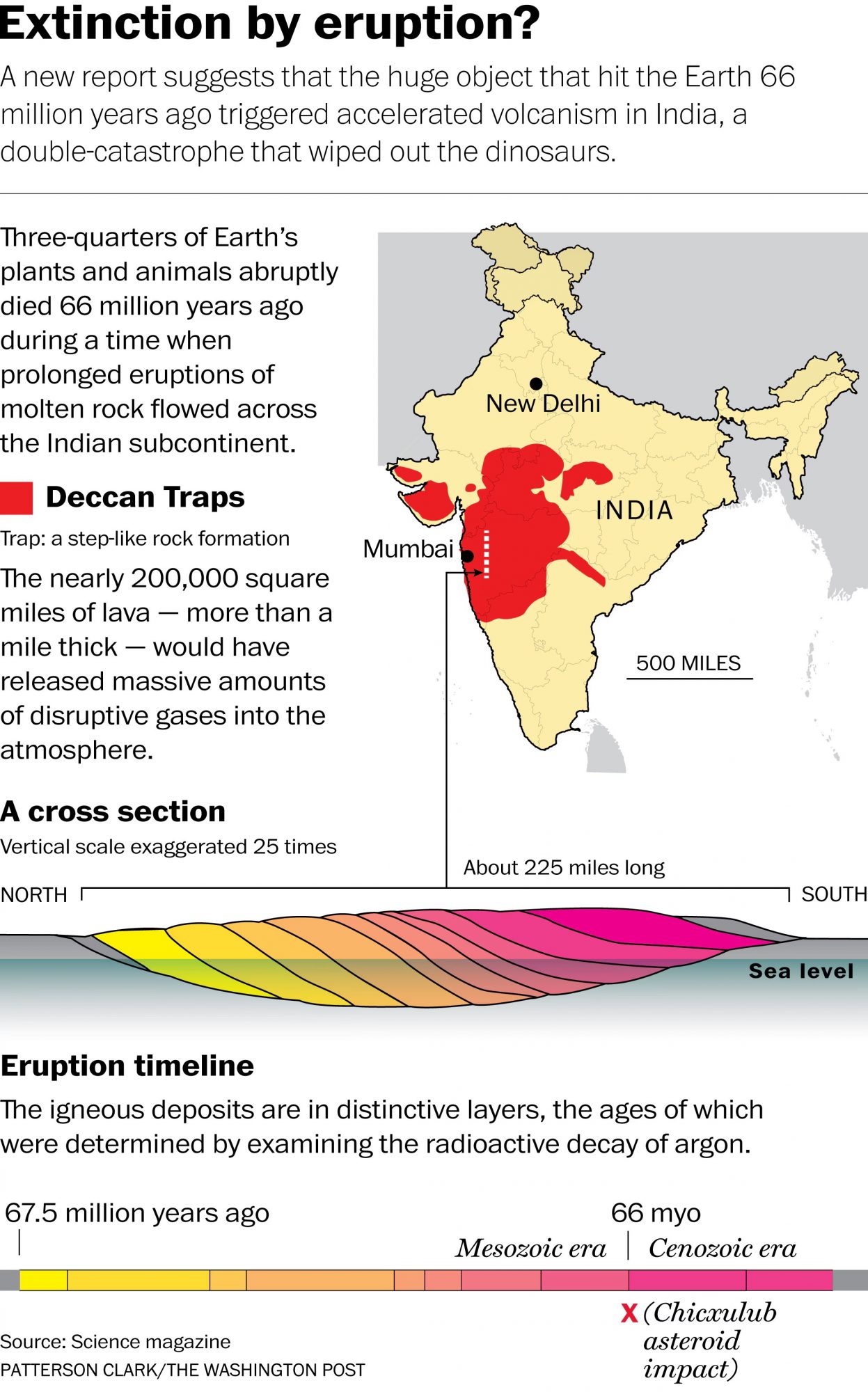

Not all geologists and paleontologists have been convinced however. You see the debris from a massive volcanic eruption looks pretty much the same as that from a collision with an asteroid. In fact it is pretty well established that the mass extinction at the end of the Permian period 250 million years ago was caused by thousands of years of extensive volcanic eruptions in what is now Siberia. Many scientists suggested that, while the asteroid strike undoubtedly did occur, volcanic activity may have contributed to, if not actually caused the extinction of the dinosaurs.

In fact there is considerable evidence for just such volcanism on the Indian sub-continent that has been estimated to be at almost the same time as the asteroid strike. So for the last decade or so the questions have been, how close in time were the two cataclysms, and how extensive was the destruction caused by the Indian volcanoes.

Now a new paper from paleo-climatologists at Utrecht University and the University of Manchester has eliminated volcanoes as a possible cause for the dinosaur extinction. What the researchers did was to examine samples from multiple levels in fossilized peat bogs found in the western United States in order to develop a detailed timeline of global temperatures in the millennia both prior to and after the asteroid strike.

As reported in their paper, which was published in the journal Science Advances, the volcanic activity in India occurred approximately 30,000 years before the asteroid. While the effect of the gasses from the volcanoes did cause the planet’s temperature to drop by some 5ºC by 10,000 years later the Earth’s temperature had returned to its value from before the eruptions. That was fully 20,000 years before the asteroid would strike. The paleontologists therefore concluded that the volcanic activity in India had minimal if any effect on the extinction of the dinosaurs.

This means that the data gathered by the researchers in Utrecht and Manchester pretty much seals the deal, the dinosaurs, and many other species were driven to extinction when a piece of the sky fell upon the ground. Of course, if it weren’t for that asteroid, we wouldn’t be here. It was just a stroke of luck that our ancestors survived while the dinosaurs all died.

Maybe we won’t be so lucky next time.