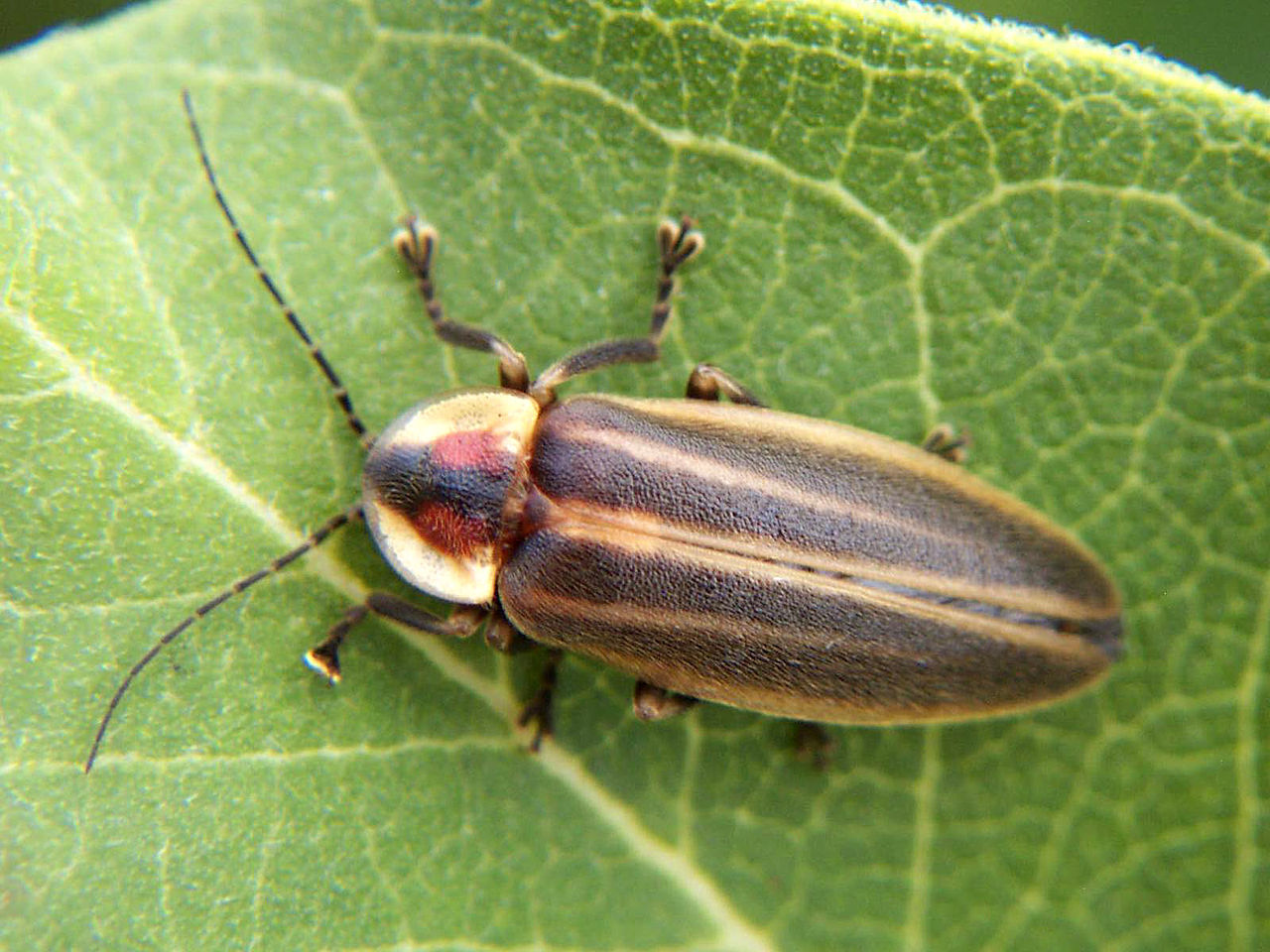

Last night, after I had switched off the light in my bedroom and before I could get into bed I saw a small, brief glow of light only about a meter in front of my face. A firefly, Photuris lucicrescens, had somehow gotten into my bedroom.

Now I’ve a lot of experience in handling fireflies going back about sixty years now so I quickly, and carefully caught the little guy and released him back outside where at least a dozen of his friends were waiting for him. But it got me to wondering, why was I so nice to a firefly when any other bug or spider that gets in my house I’ll just swat or squish.

It’s bioluminescence, that small glow that gives fireflies their name that makes them pretty to us. Catching fireflies on a warm summer’s night is a game no child can resist but even as a child I would always let the creature go after playing with it for a few minutes. The fact that a living creature, a small insect can generate light within its body mystifies and delights us.

Bioluminescence occurs in a wide range of living things both aquatic and terrestrial. Everything from bacteria and fungi to molluscs, arthropods and even species of vertebrates have shown bioluminescence. Although many creatures, like the firefly produce their light using their own metabolism there are other animals, such as the deep-sea anglerfish, who obtain their light by growing bioluminescent bacteria within their bodies. Bioluminescence is so spread out, here and there across so many different kinds of living things, at least 11 different animal phyla and several of fungi and plants that biologists are convinced that the ability of a living thing to produce light has evolved independently more than 40 times in the history of life.

Because there is such a wide diversity of living things that produce bioluminescence the early study of the phenomenon concentrated on individual species rather than examining it as a single subject. While both Aristotle and Pliny the Elder discussed the glow produced by damp, dead wood it wasn’t until centuries later that Robert Boyle showed that the gas oxygen played a major role in producing the light. And even then it took more than another hundred years, until 1854, that Johann Florian Heller finally discovered that it was actually a fungus growing in and consuming the wood that was producing the light.

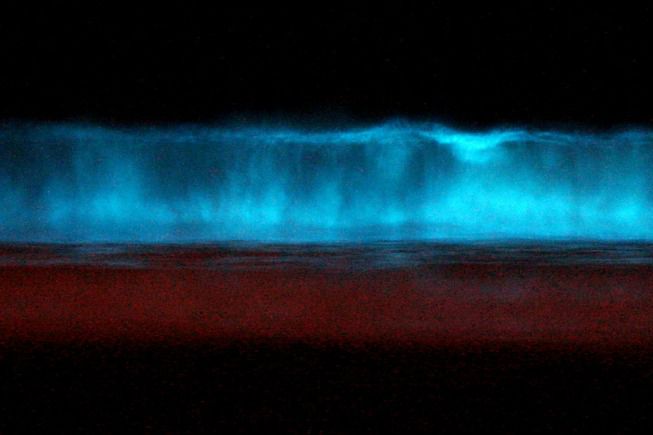

At about the same time Charles Darwin suggested that the bioluminescence often seen in the tropical ocean capping crests of waves and illuminating the wakes of ships was due to ‘minute crustacea’, one of the few times he was wrong in his hypothesis. The greenish light that is produced in disturbed ocean waters is in fact caused by several species of dinoflagellates in the plankton.

It is really only since the mid 20th century that the chemical processes that generate bioluminescence have been adequately described. Simply put the chemical reaction involves an organic pigment referred to as the luciferin, which is induced to emit light by an enzyme called the luciferase. Problem is that there are so many different chemicals that living things use as their luciferin and luciferase that the only thing that can be said about the reactions in general is the use of oxygen as the source of energy. The fact that so many different chemical reactions can produce bioluminescence is undoubtedly one of the reasons that the ability has evolved independently so many times.

And with so many different kinds of living things using bioluminescence it’s hardly surprising that they use it in a wide variety of different ways. It is well known that the fireflies in my backyard use their glowing tails as a means of attracting a mate; it’s only the male who does the blinking by the way. Deep-sea anglerfish on the other hand use their bioluminescence as a lure to draw smaller fish in close so that they can then eat’em.

Those are two of the more straightforward uses of bioluminescence; some others are not so obvious. For example the glowing of fungi in damp, dead wood that Aristotle noticed. It is thought by some naturalists that the glow might cause insects or animals to come and investigate, the fungi then is able to spread some of its spores onto the animal’s skin, feathers or fur. Those spores may then be able to pass on to other dead, damp pieces of wood allowing the fungi to propagate.

Many species of cephalopods, squid and octopi use bioluminescence as a defensive measure. Whenever they feel threatened they will squirt out a cloud of bioluminescent material that startles and blinds the attacker allowing the cephalopod to escape, sort of the exact opposite of the black ink used by other cephalopods for the same reason.

Since we humans have always been intrigued by bioluminescence it’s not surprising that genetic researchers have been playing around with the genes responsible. As far back as 1986 the firefly gene that produced its version of luciferin was successfully implanted into tobacco plants. Currently there is a considerable amount of research underway to see if bioluminescent bacteria can actually be used to manufacture a form of living light bulb. Such a light bulb would not require electricity to generate light but as you might guess the greatest difficulty at present is the low light intensity, the low amount of energy in other words.

Whether or not any of these experiments manage to develop something that is practical, something of commercial value is questionable at the moment. Still bioluminescence has always fascinated us, so much so that scientists will keep on studying it, if only for a bit of fun.