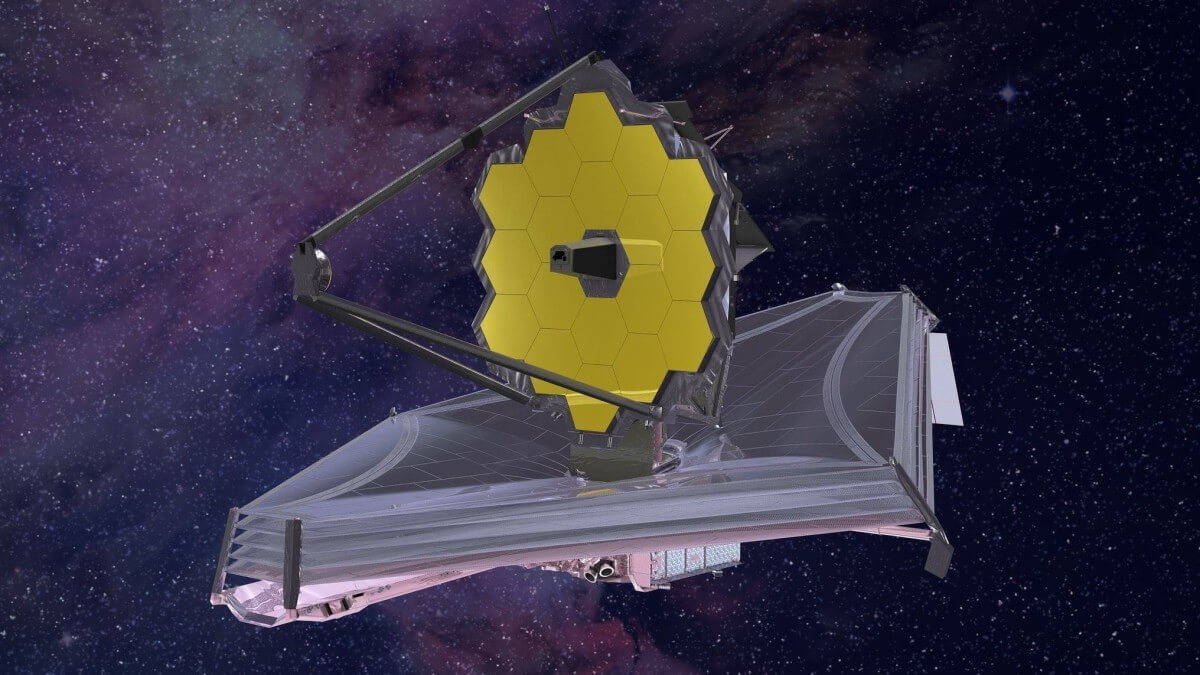

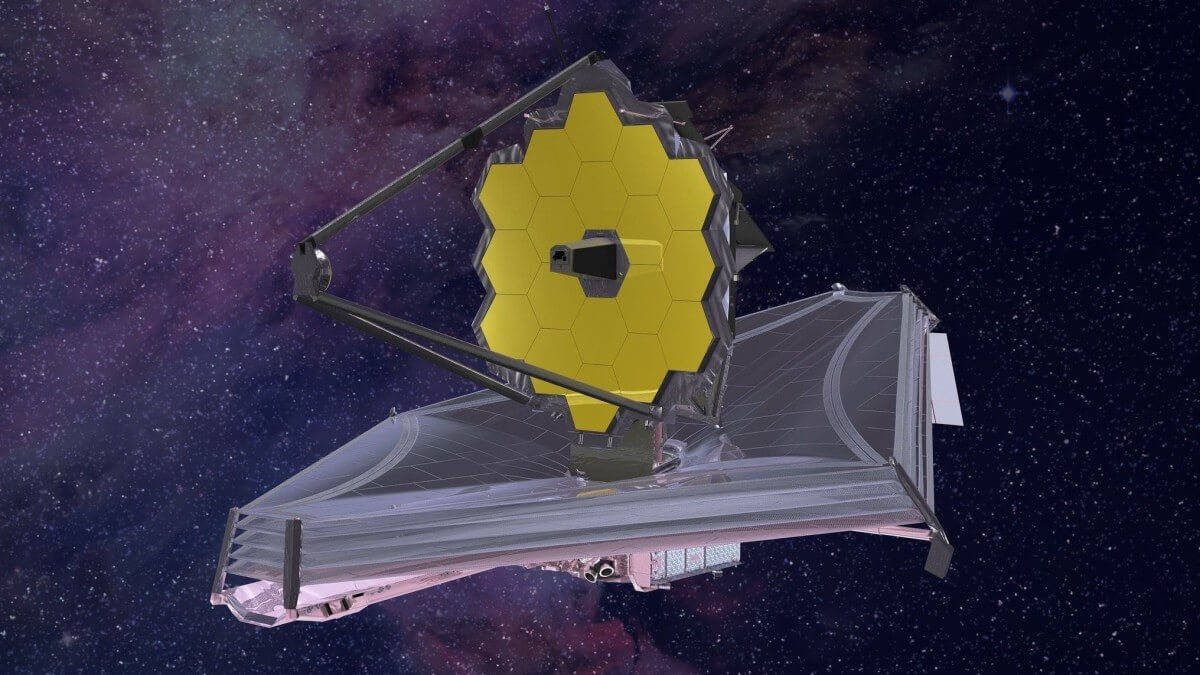

Lifted into orbit back in (December of 2021) the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) spent its first months in orbit calibrating its instruments while the world’s astronomers eagerly waited. Well JWST has been in operation for a little over a year now and NASA has taken the opportunity to release some of the more spectacular images sent back by the space telescope.

First a bit of a reminder, JWST operates as most large astronomical telescopes do by taking long exposure digital images of whatever astronomical object it is studying. Most of those ‘deep space’ objects are actually very dim and the only way to get good images is to open up the telescope’s camera and allow the light to gather photon by photon over a long period of time. The images are then computer enhanced to bring out the details the astronomers are interested in. In other words the pictures released by NASA are not what you would see if you actually looked into a telescope at the same object.

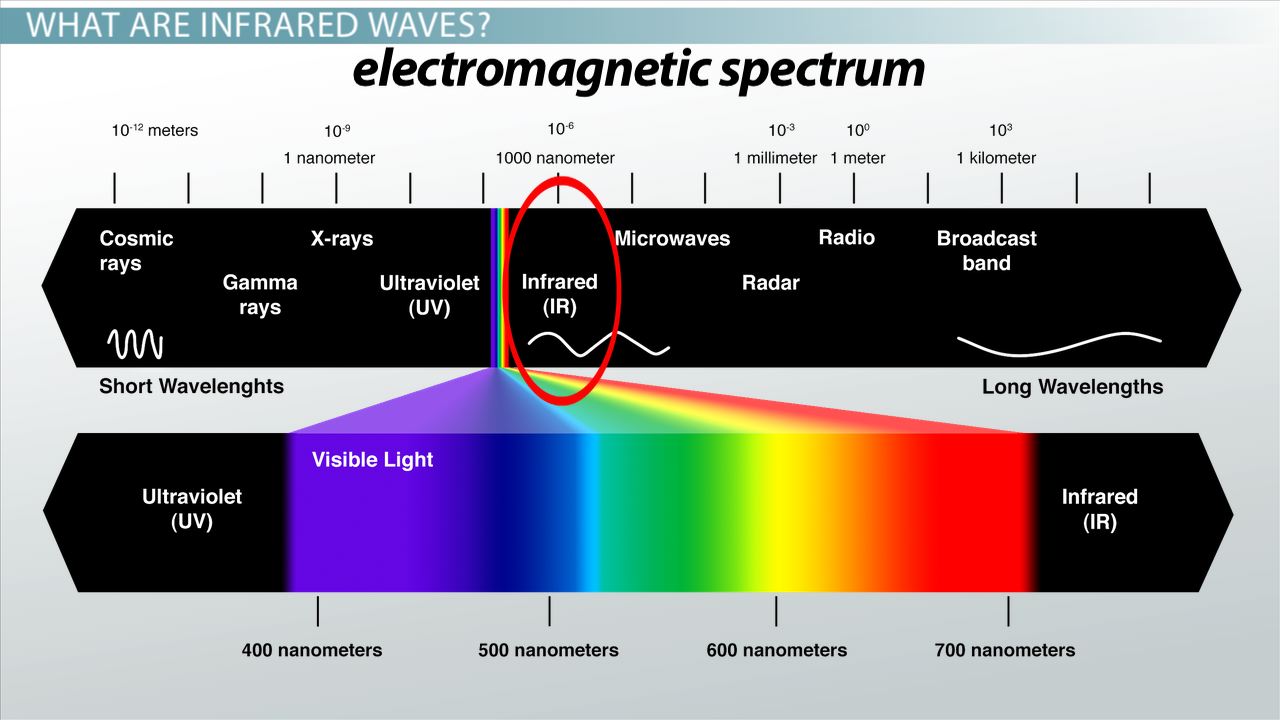

Another big difference between JWST and other telescopes, even the Hubble Space Telescope is that JWST views objects primarily in the infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. This allows JWST to see details that are completely invisible to our eyes. That is the reason that JWST had to be placed more than a million kilometers from the Earth because the infrared light coming from both the Sun and the Earth would blind it if it weren’t protected. Again the digital images taken by the JWST in the infrared are then converted by a computer into visible images for astronomers, and the rest of us to see.

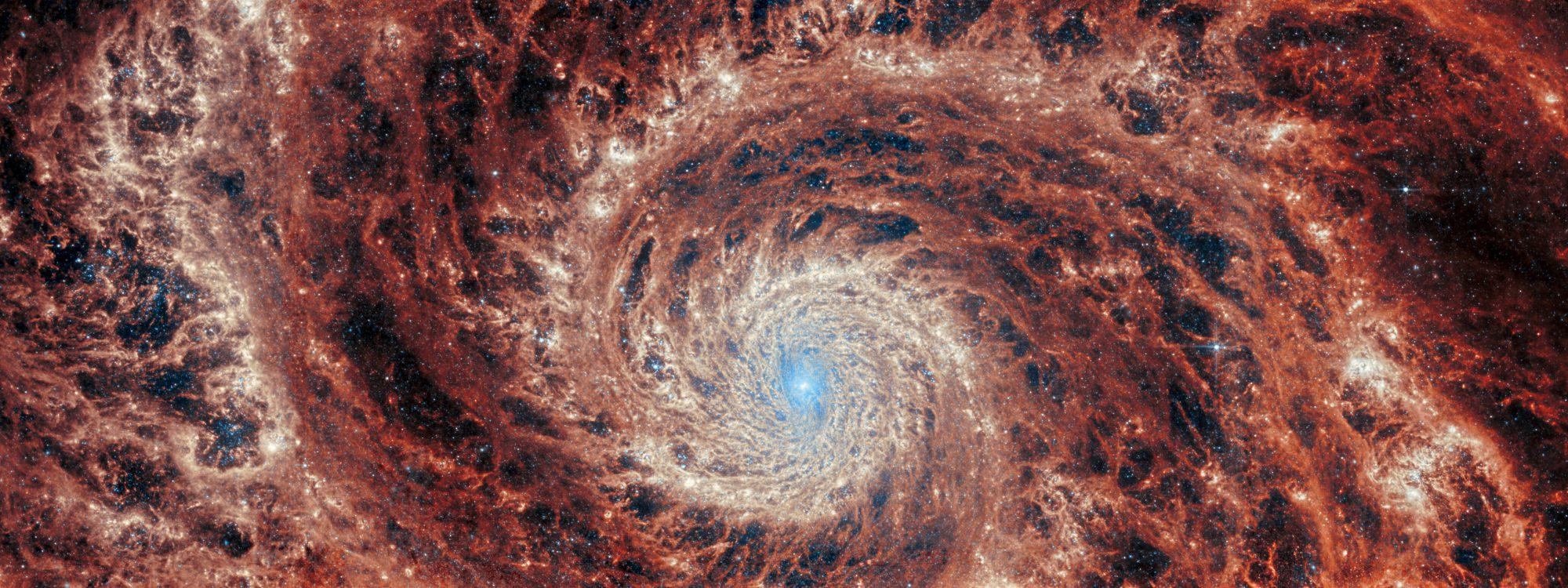

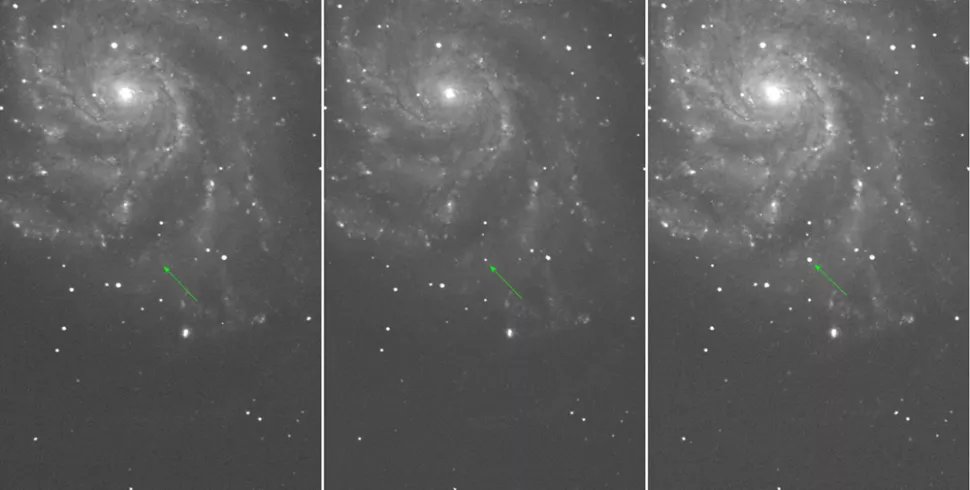

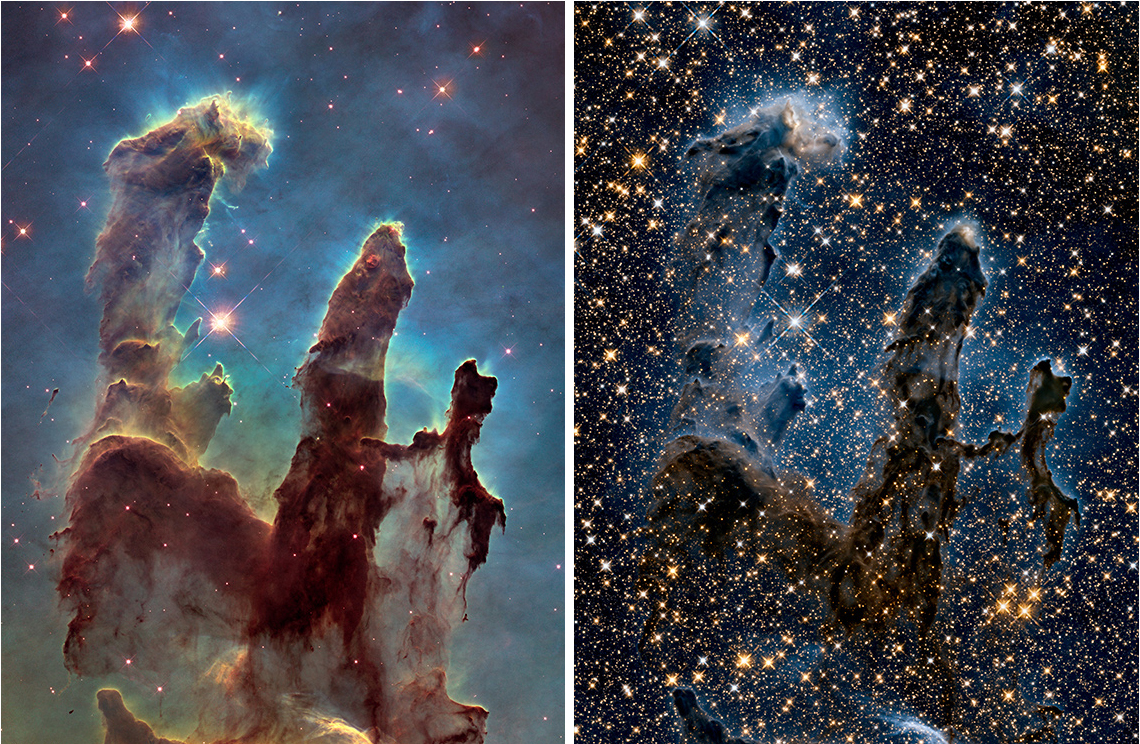

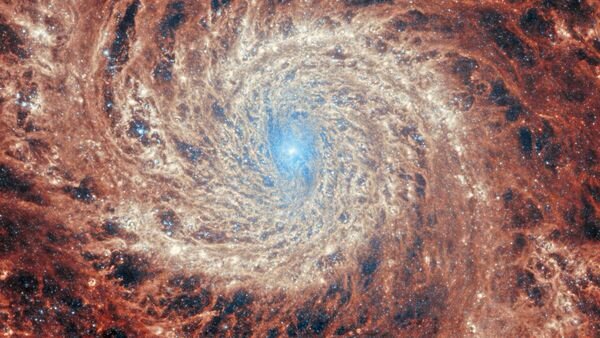

The first set of images released from the JWST team at (John Hopkins Physics Lab) was of the well known ‘Whirlpool Galaxy’ often referred to as Messier 51 or just M51. At a distance of 27 million light years from Earth this galaxy is a favourite target of amateur astronomers not far from the Big Dipper in the sky. While M51 is a typical spiral galaxy it happens to be facing our galaxy almost head on so that our view of its spiral arms is simply magnificent. A very beautiful image of M51 was taken by Hubble a dozen years ago and astronomers have been itching to get a view with JWST ever since.

Now they’ve done just that and the image is beyond expectations. One of the reasons JWST operates in the infrared is that infrared light can pass through the gas and dust that tends to blur the details in the spiral arms of galaxies like M51 in visible light. That means that JWST sees deeper into the galaxy, imaging structure never seen before. The same is also true of the small dwarf galaxy NGC 5195 located at the end of M51’s ‘tail’ and whose gravitational field is actually responsible for much of the structure of the Whirlpool’s spiral arms. Images such as JWST’s of the Whirlpool not only are beautiful but they give astrophysicists a lot of data to use in their efforts to understand how galaxies are structured and how they change with time.

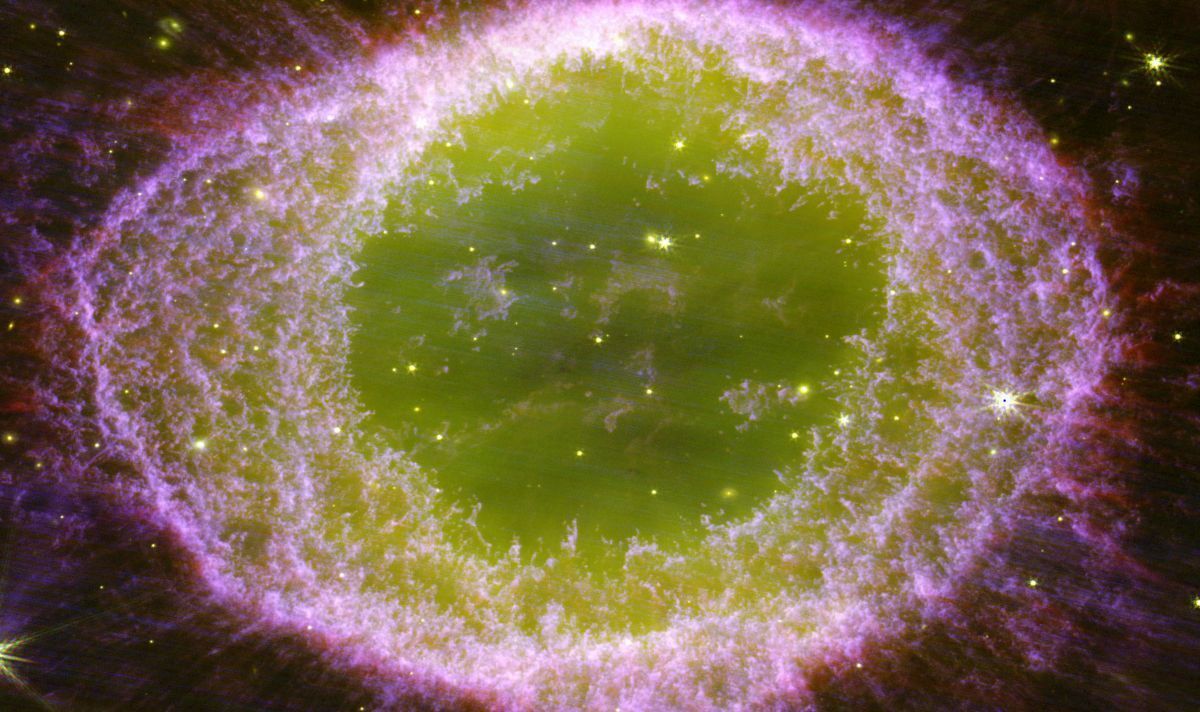

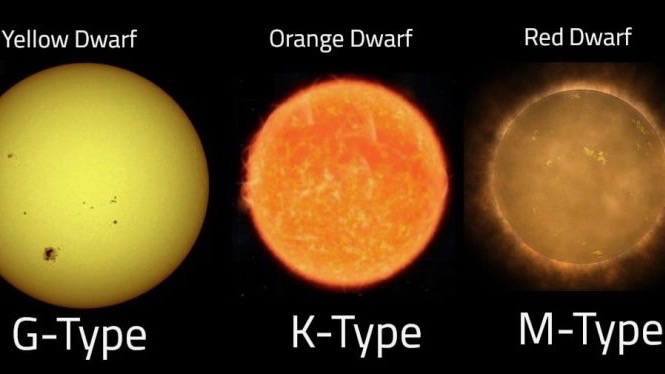

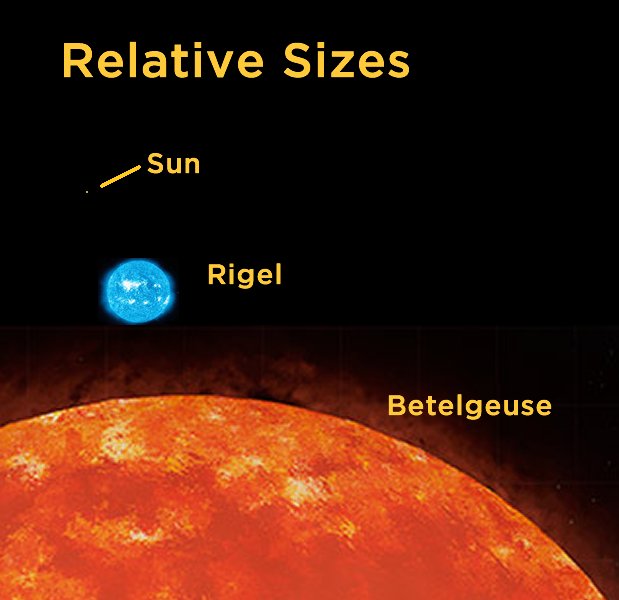

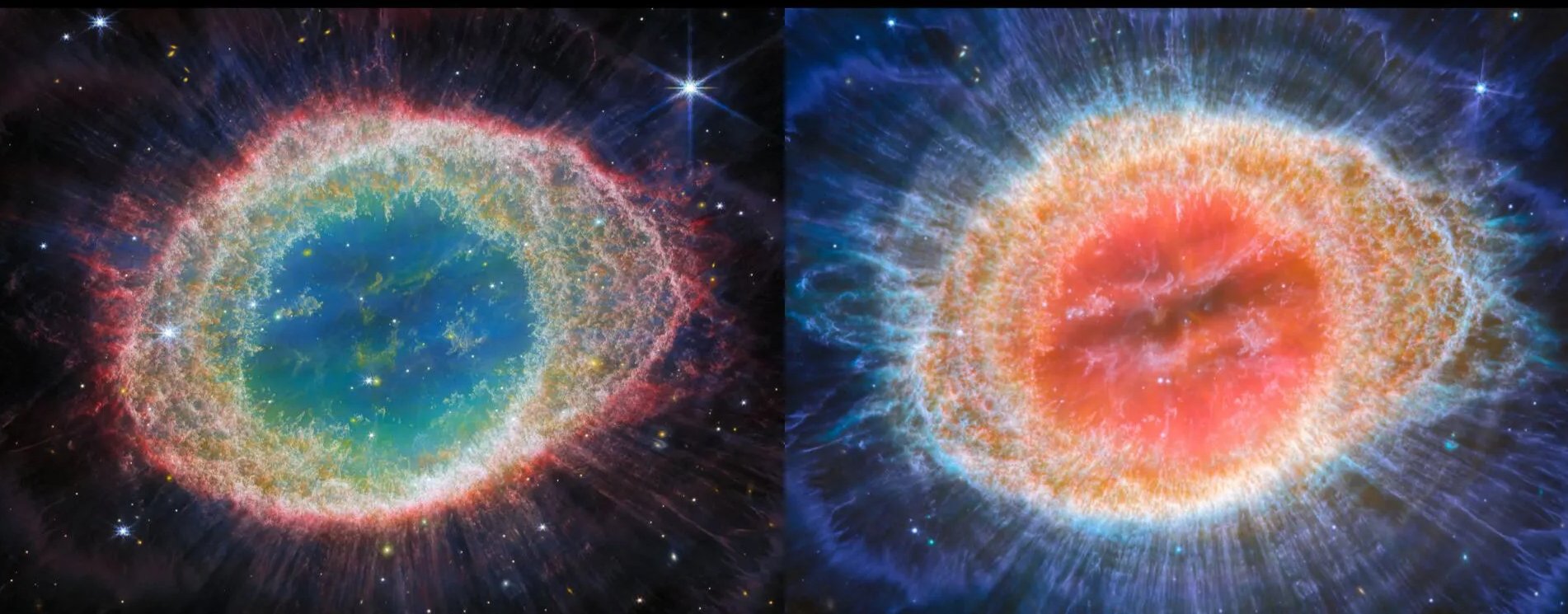

The next astronomical object that the JWST team released images of was a lot closer to home, a mere 2,600 light years away. The Ring Nebula or M57 as it is known is located in the night sky near the bright star Vega and is in many ways a glimpse into the future fate of our own Sun. The star at the center of the ring was once about the same mass as our Sun but about a billion years ago it used up all of its hydrogen fuel and began to burn helium. In order to do that the star’s core had to get smaller and hotter which caused its outer regions to puff up making the star a ‘Red Giant’.

Then, less than a million years ago the star started to run out of helium so again its core got smaller and hotter, so much so that its outer regions were ejected from the star into interstellar space. This material was mostly ejected from the star’s equatorial region so it formed a ring around the original star, the Ring Nebula.

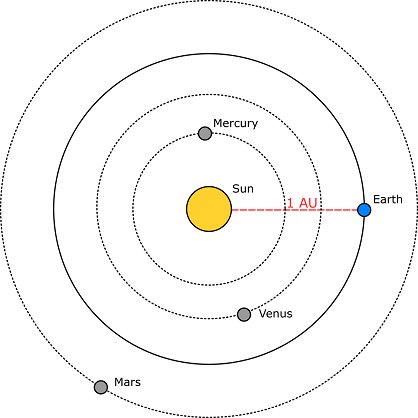

Since the ring itself is made up of gas and dust JWST’s ability to see in the infrared makes it the perfect instrument with which to study M57. The images taken by JWST show an enormous amount to detail that was never seen before including about 20,000 dense clumps of matter and a halo of 10 concentric arcs with 400 spikes. JWST also discovered that the central star causing the ring is not alone, it has two smaller companion stars, one about 35 astronomical units (AU) from the central star, an astronomical unit is Earth’s distance from our Sun, and the other more distant at 14,400 AU.

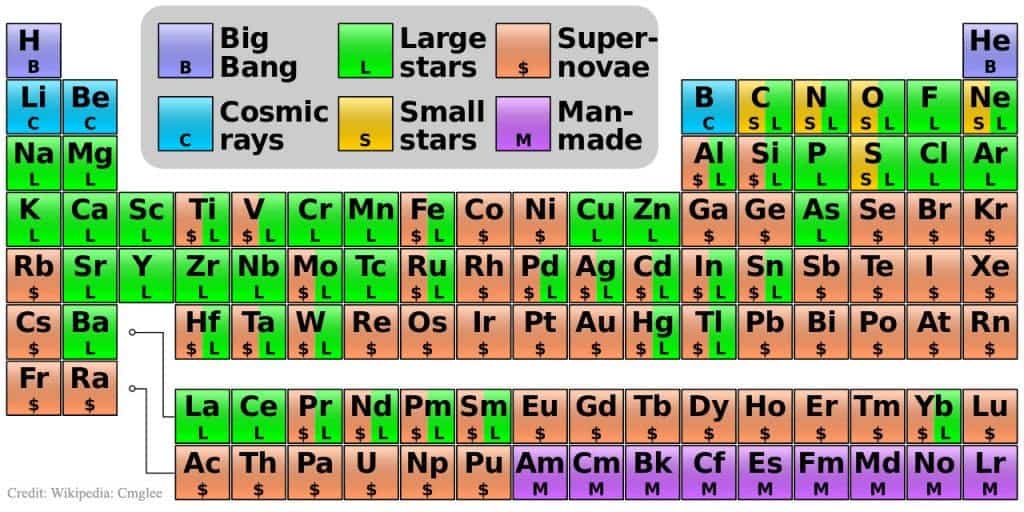

Like the images of the Whirlpool galaxy astrophysicists will have plenty to keep them busy analyzing what JWST has found at the Ring Nebula. Nebulas like the ring are not only important because they show our Sun’s future but also because the material ejected from such nebula is how heavier elements like Oxygen, Carbon, Nitrogen and Silicon get spread around the galaxy so that they can form planets like our Earth.

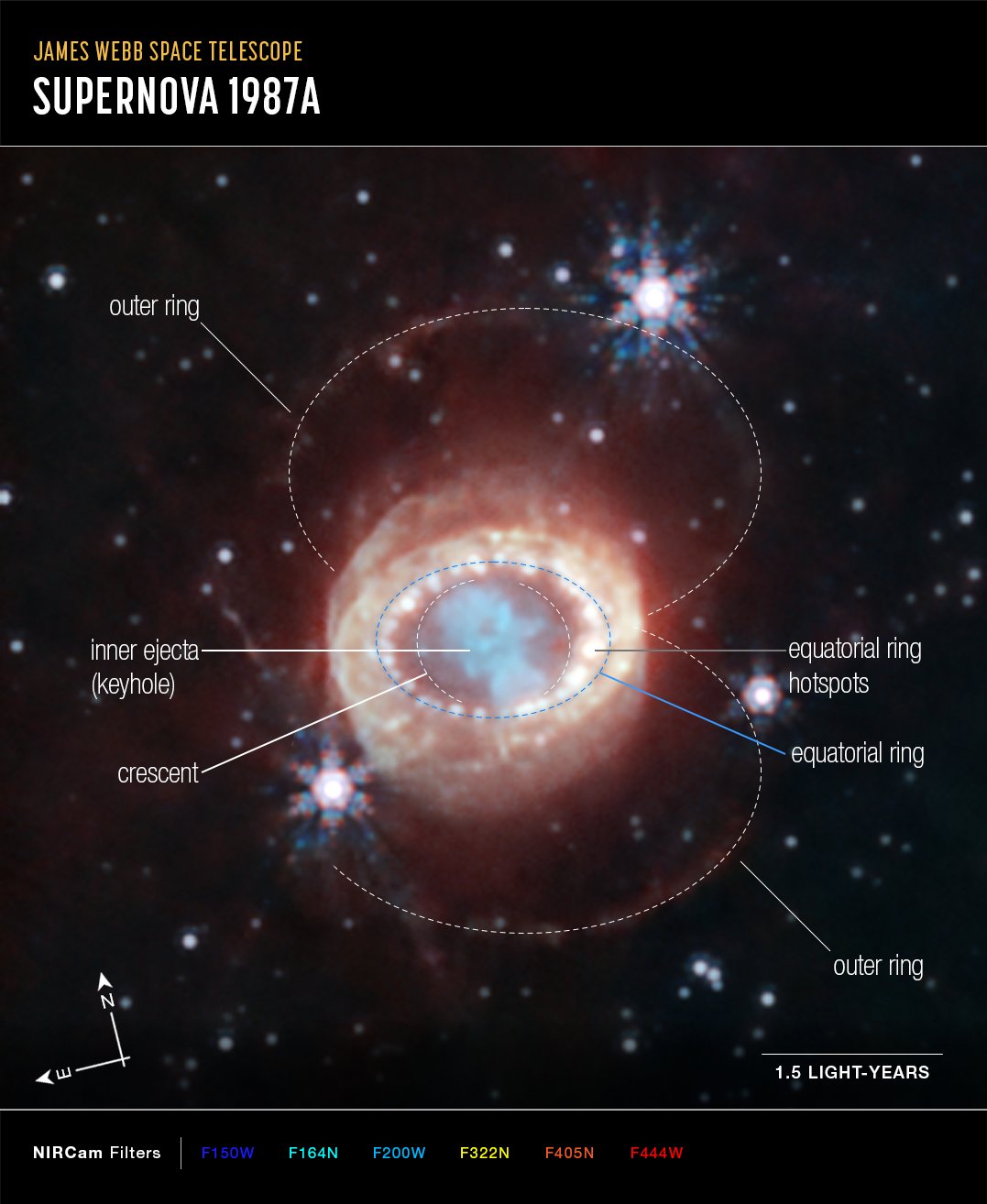

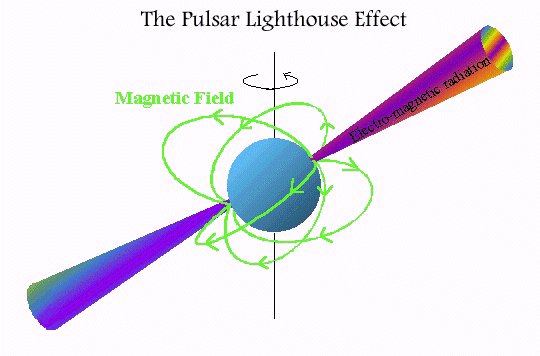

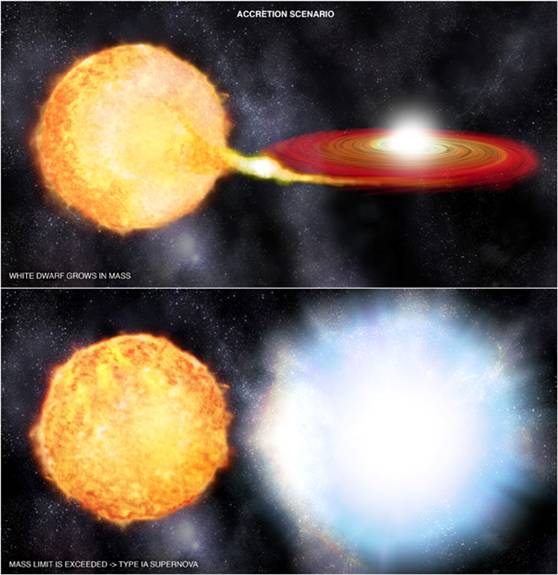

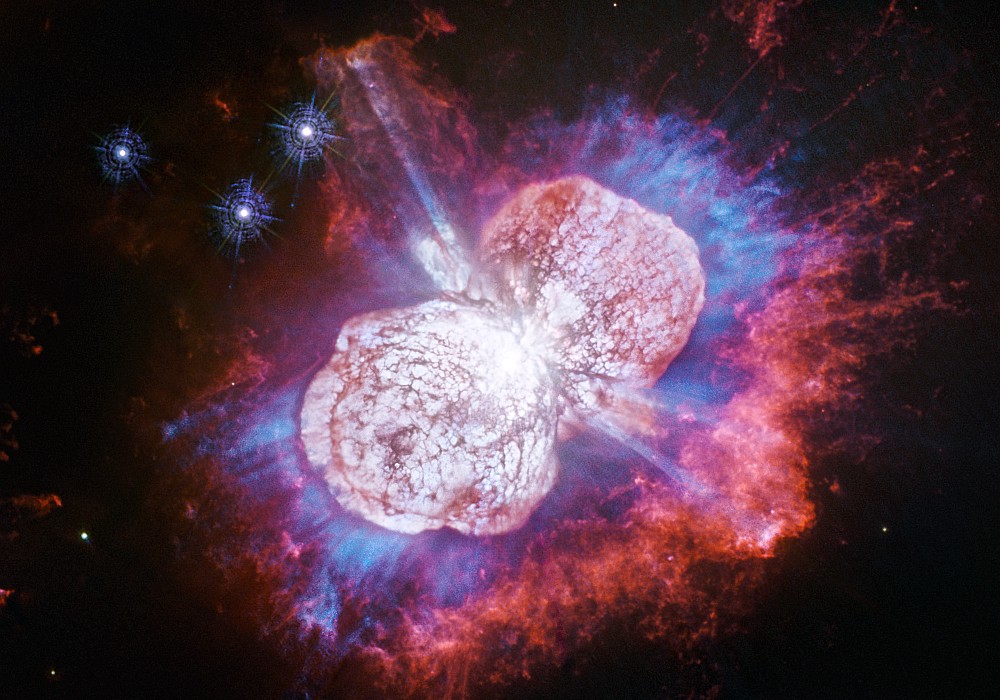

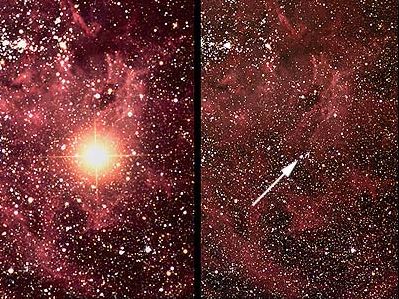

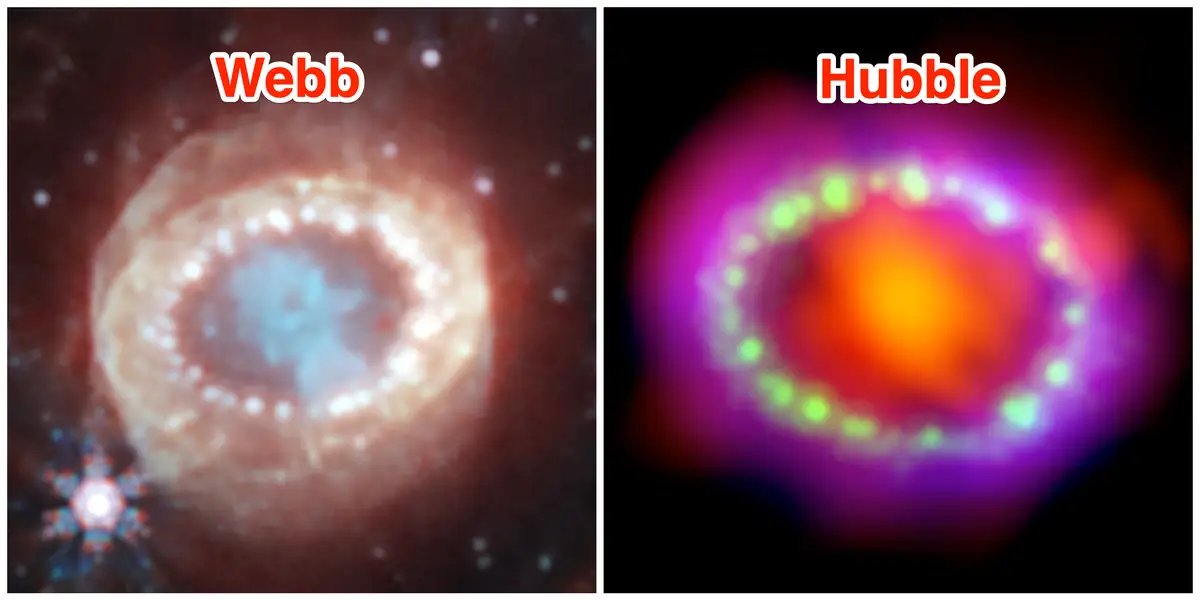

The final set of images taken by JWST are of Supernova 1987A (SN1987A), the closest supernova to Earth in the last 400 years and the only supernova to date for which we have a picture of the star taken before it blew up. Supernova are rare events that only happen when a huge star, at least 20 times the mass of our Sun has used up all of the nuclear fuel available to it. When that happens the star’s core collapses into a neutron star or even a black hole. The rest of the star explodes in one of the most powerful events in the Universe.

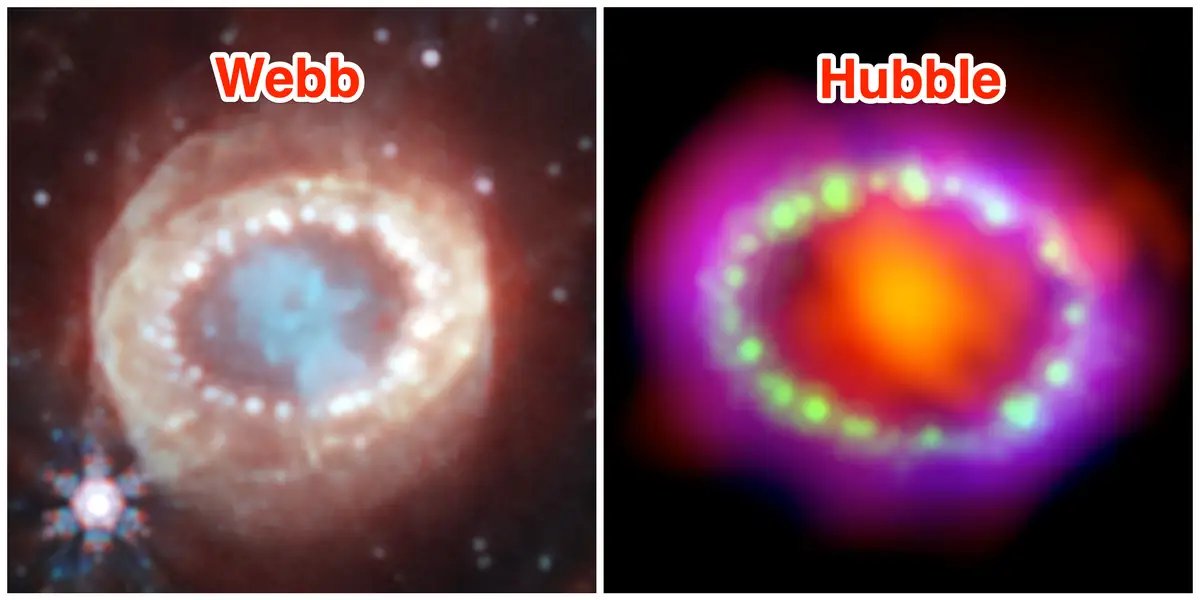

Obviously studying supernovas is a lot of fun but the problem is that they are so rare that detailed data is hard to get, most of the supernovas observed by astronomers are in galaxies billions of light years away. That’s why astronomers were so anxious for JWST to observe SN1987A. The Hubble space telescope had been observing the supernova for years and had watched as the shock wave from the explosion caught up to and slammed into material ejected from the star before it went nova.

The images from JWST show that collision in even greater detail with a cluster of material that looks like a string of pearls. The JWST will continue to observe the dynamic changes around SN1987A while also searching for the neutron star that must have formed in the explosion but which so far has eluded detection.

The images released by the team (at Johns Hopkins) are just the beginning of the marvels that astronomers hope JWST will reveal in the years to come. Just as Hubble altered and illuminated our view of the Universe JWST is sure to do the same.