We all learned about sunspots back in high school. You know those dark patches on the Sun’s surface that are actually magnetic storms the size of our entire planet or even larger. And you may recall that sunspots have an eleven year cycle starting with a minimum where few if any sunspots occur, growing to a maximum where the Sun’s face looks like it’s broken out in acne and then back to a minimum eleven years later. (That figure of eleven years by the way is approximate. The actual length of a solar cycle often varies by one or two years either way.) Finally, if you were interested you may have also heard that since sunspots are magnetic in nature they come in pairs with one being a north magnetic pole and the other a south magnetic pole.

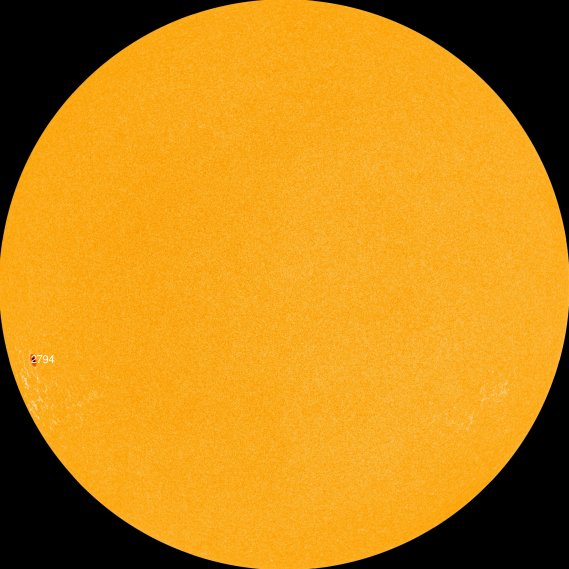

Earlier this year the Sun went 200 consecutive days without a single sunspot showing on its visible face, and that was on top of a very small number of sunspots last year so obviously that period was a very deep minimum. Over the last four months or so however things have definitely started to pick up with a small number of fairly strong sunspots developing on the Sun’s surface.

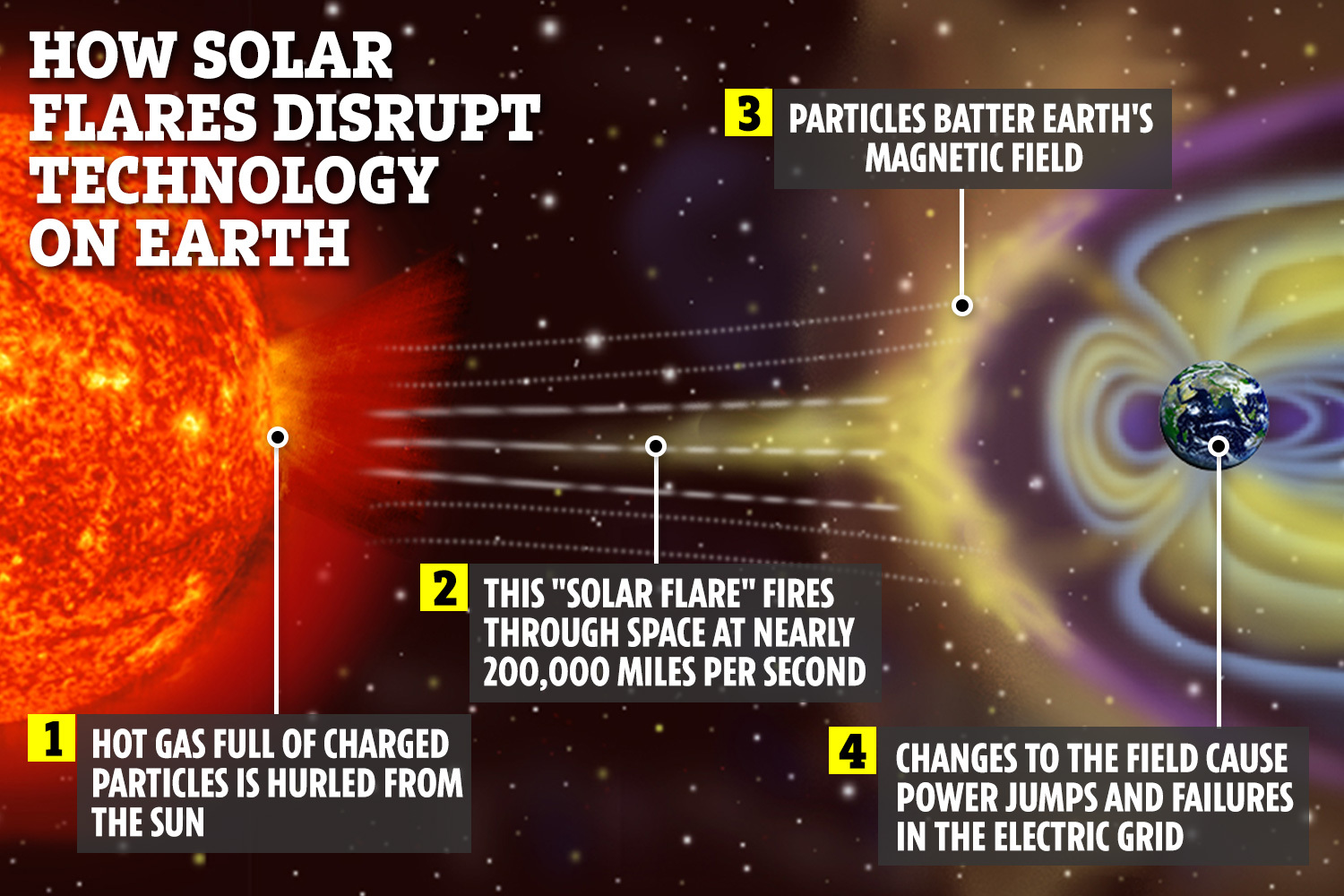

This increase in solar activity marks the beginning of solar cycle number 25, which since a solar cycle is about eleven years means scientists have been keeping track of sunspots for 260-270 years! The question now is whether the upcoming solar maximum, expected in 2025, will be another weak one as the last two have been, or will there be a dramatic increase in the number and strength of sunspots during the next maximum. The answer is important to our modern technological civilization because more solar activity means more solar flares blasting out powerful Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs). These CMEs can collide with the Earth as powerful electrical disturbances that interfere with satellites in orbit, power grids here on the ground and radio transmissions around the world.

The official estimate coming from NASA and NOAA is that Cycle 25 will be a relatively weak one similar to the last two. However a team of solar scientists from the University of Warwick and the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) are using a new theory of solar activity to predict that the upcoming solar cycle will be one of the most powerful ever recorded.

The new theory pays attention to those sunspot cycles that are either longer or shorter than average and maps them against a 22 year long cycle. What they found was that a long solar cycle, such as cycle 23 which lasted 13 years, is followed by a weak sunspot cycle while a short cycle, cycle 24 was not only weak but also quite short at a little less than ten years, gets followed by a strong, active sunspot cycle.

The new theory already seems to be gaining evidence because cycle 25 is off to a strong start. In addition to several large sunspots there have been two powerful solar flares, one of which on December 7th sent a CME headed straight at Earth. The CME arrived here on the 9th producing auroras that were more powerful, and came further south than any in recent years.

And solar astronomers now have newer, better more sensitive instruments with which to observe the forthcoming Solar Cycle. One of these is the Parker Solar Probe that is currently in an orbit around the Sun that is slowly getting closer and closer and which will come as close as 6 million kilometers in the year 2025. I wrote about the Parker probe in my posts of 12Feb20, 18Dec19, 3Nov18 and 5Sept18 but today I’d like to discuss the National Science Foundation’s brand new Inouye Solar Telescope.

Now nearing completion as the world’s largest solar telescope, the Inouye is named for Hawaiian Senator Daniel J. Inouye, who was a strong supporter of the Mona Kea observatory on the island of Maui, the big island in the Hawaiian chain. Possessing a primary mirror 4 meters in diameter and with the latest advanced optics the Inouye will increase by a factor of 2.5 our resolution of Solar images showing previously unseen details that the theoreticians can use to check against their models.

With that improved resolution it is expected that the Inouye will be able to see structures as small as 20 km across on the Sun’s surface. Since it is designed to capture and observe the light of the Sun the Inouye also has some equipment not normally found in a telescope, specifically a cooling system to keep the energy gathered from the Sun from overheating the entire system.

With advanced equipment like the Inouye Solar Telescope and the new theories developed by Solar astrophysicists Sunspot Cycle 25 promises to be an exciting one. Hopefully over the next few years many new discoveries will be made as we seek to learn the secrets of our nearest star.