There have been some important fossil discoveries lately that span nearly the entire time period of multi-cellular life on Earth. I think I’ll start with the earliest and work my way forward in time.

We usually think of complex social behavior as being a recent development in the history of life. After all we have the most complex societies of any species and we’re one of the youngest of Earth’s creatures, right?

Well it is worth remembering that some insects like ants have been living together in complex hives for around 200 million years and we now know that many species of dinosaurs traveled in herds for protection. So obviously some forms of social behavior predate human beings by quite a long time.

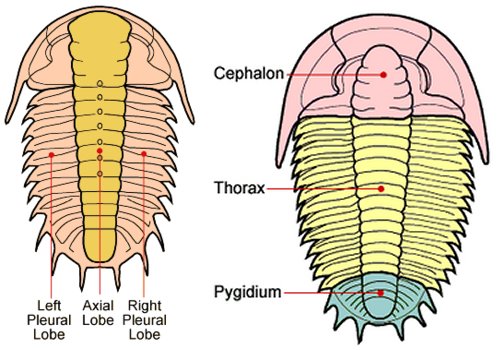

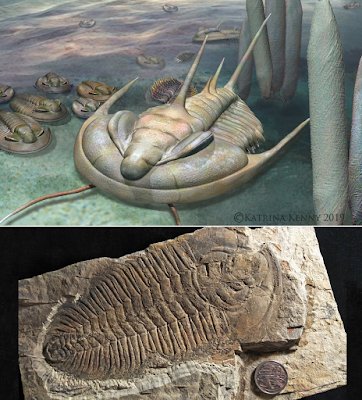

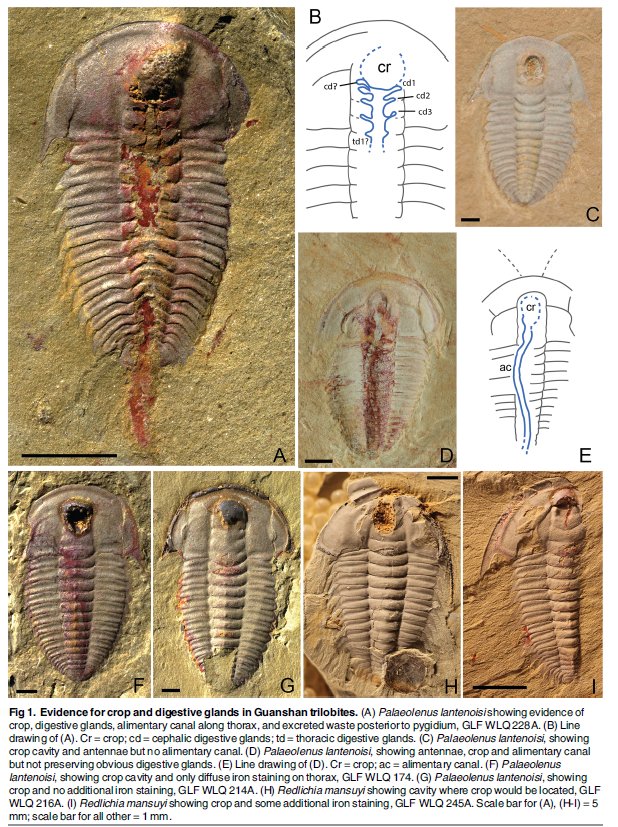

Now a new series of fossils from Morocco is providing evidence that social behavior existed as far back as the lower Ordovician period, about 480 million years ago. The fossils shown a large number of individuals of the trilobite species Ampyx priscus arranged in a line with the front end of their bodies all pointing in the same direction. The clear indication is that these creatures were moving together in a very orderly line, a behavior requiring considerable neural and sensory ability.

The reason why these trilobites were moving together in a line will probably never be known for certain but the fact is that arthropod species like spiny lobsters, ants and even caterpillars are known to behave in a very similar fashion today. These trilobites provide another example of how old doesn’t necessarily imply simple or primitive.

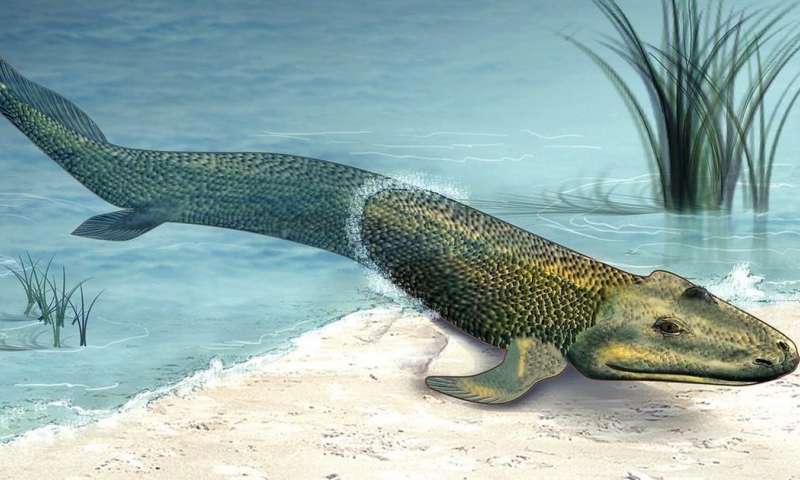

One of the critical events in the history of life on this planet has to be the moment when the first vertebrate animal, a fish, climbed out of the water and gingerly set foot on the land. All land dwelling bony animals, all amphibians, reptiles, including the dinosaurs, birds and mammals, including you and I are beholden to that ancient creature.

So it’s not surprising that paleontologists are keenly interested in learning as much as they can about those early land vertebrates. The recent discovery of a new species of tetrapod, that is a four-limbed animal, gives an insight into what kind of creature may have been the first to make that historic step. Discovered in the Sosnogorsk formation along the banks of the Izhma River in the former Soviet Republic of Komi the animal has been dated to about 372 million years ago during the Devonian Period.

Named Parmastega aelidae the animal is a strange mixture of both fish and land animal characteristics. For example the placement of its eyes on the top of a flat skull clearly indicates an animal that is watching what is going on above the waterline. At the same time however the animal’s shoulder girdle is made of partially cartilaginous bones, making those bones too weak to be able to support a land animal. So P aelidae may have been a water animal whose prey lived out of the water. A modern example would be a crocodile and indeed the long snout filled with sharp teeth of P aelidae strongly resembles that of a crocodile.

The discovery of such fossils as P aelidae gives us further knowledge in our quest to understand how our ancestors evolved to become the dominant kind of life on land.

Another critical moment in the history of life on Earth surely came after the asteroid collision that led to the extinction of the dinosaurs along with 75% of all species of life. The questions of how quickly did life recover from that disaster, and what kind of animals became dominant now that the dinosaurs were gone are key to our understanding the natural world today? Paleontologists know that in order to answer these questions they need to find fossil sites from the time immediately after the asteroid strike.

Just such a fossil site was recently discovered by paleontologists Tyler Lyson and Ian Miller of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science just outside the nearby city of Colorado Springs. The location, known as Corral Bluff is yielding a treasure trove of fossils from a time less than a million years after the asteroid strike. The finds include over 1,000 mammal fossils from 16 different species along with reptiles, birds and 6,000 plant fossils. The most important finds discovered by the researchers consisted of dozens of delicate mammalian skulls.

While the fossils are still being studied a few conclusions can be reached. During the reign of the dinosaurs mammals remained small, rare and nocturnal creatures no larger than a squirrel, about one kilogram maximum. The fossils obtained from Corral Bluff however show that is less than a million after the dinosaurs were gone mammals had already greatly increased in both size and number with one of the species discovered estimated as having a mass more than 50 kg.

The fossils from Corral Bluffs give witness to how quickly the mammals were evolving to fill up the ecological niches left vacant by the extinction of the dinosaurs. At the same time the paleontologists are making other discoveries as well, among them the remains of the earliest known legume, a pea plant that might very well have provided high protein food for some of the growing population of mammals.

The history of life on Earth is both long and complex but paleontologists don’t mind that at all. It just mean that there are many more fascinating discoveries waiting to be made.