There are two kinds of paleontologists in the world, field explorers who discover sites where new and exciting fossils are found, and labouratory analysts who use the fossils that are unearthed to understand the big picture of life in the past. Today’s post is about two sites where new discoveries are being made along with a new study, based on evidence from fossil sites around the world, that tackles the question of why some creatures, such as our mammalian ancestors, survived the asteroid strike 66 million years ago killed all the dinosaurs. As usual I’ll begin with the oldest story in geological time and go forward from there.

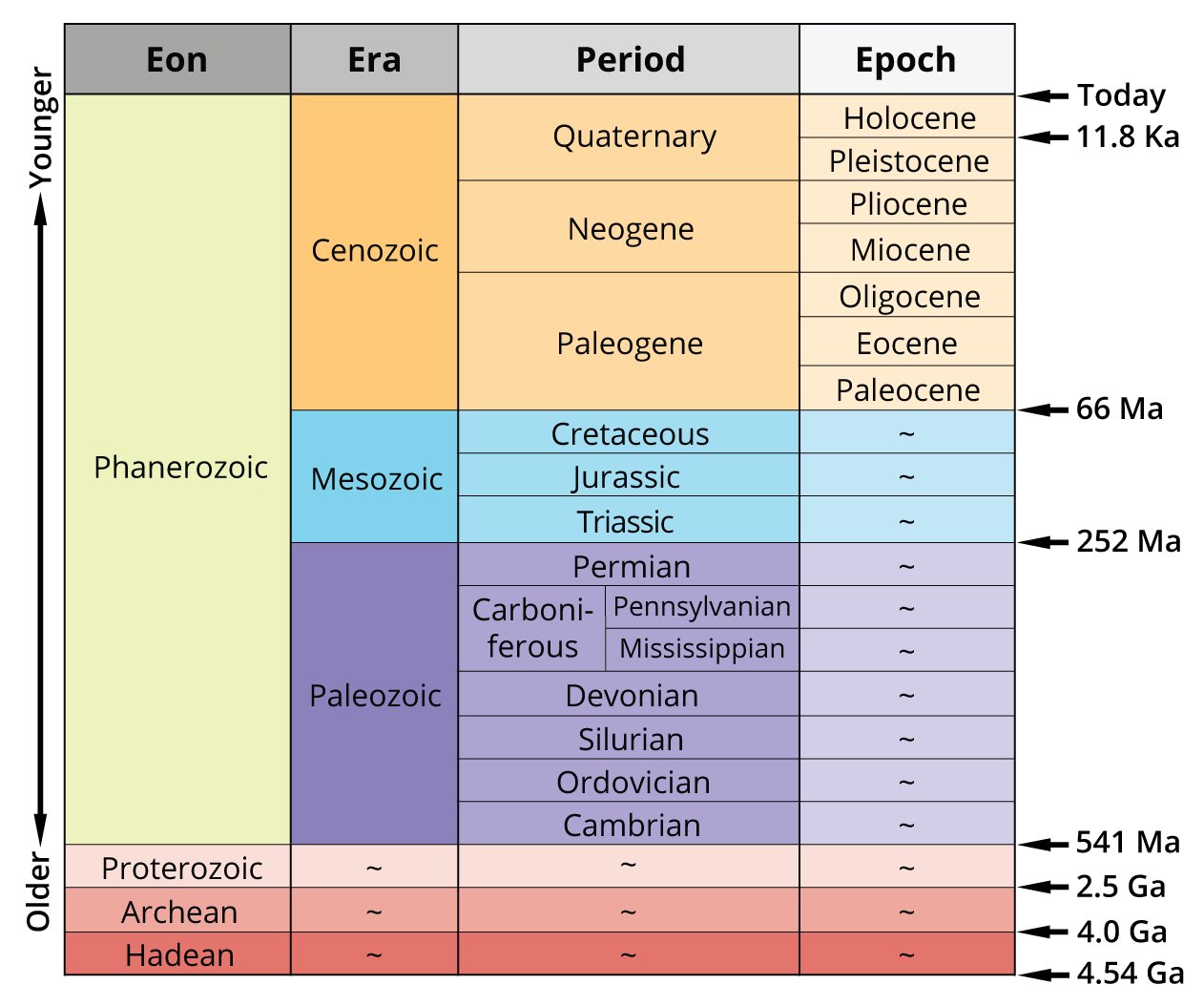

Paleontologists have categorized the history of life here on Earth into a large number of ‘periods’ some of which are better known that the others. The Cambrian period is known for being the first period with large numbers of species who possessed ‘hard parts ‘ that can fossilize. The Devonian period is known as the ‘age of fishes’ where vertebrate animals with bony skeletons began to dominate the oceans, and by the end of the period the land. The Jurassic and Cretaceous periods are both known for the many familiar dinosaur species that lived during them.

The Ordovician period isn’t that well known. Coming right after the Cambrian the animals that lived about 470 million years ago (mya) aren’t really that much different from their Cambrian ancestors. I have quite a few Ordovician specimens in my collection and they are mostly bivalved brachiopods along with a few trilobites and some other invertebrates like corals.

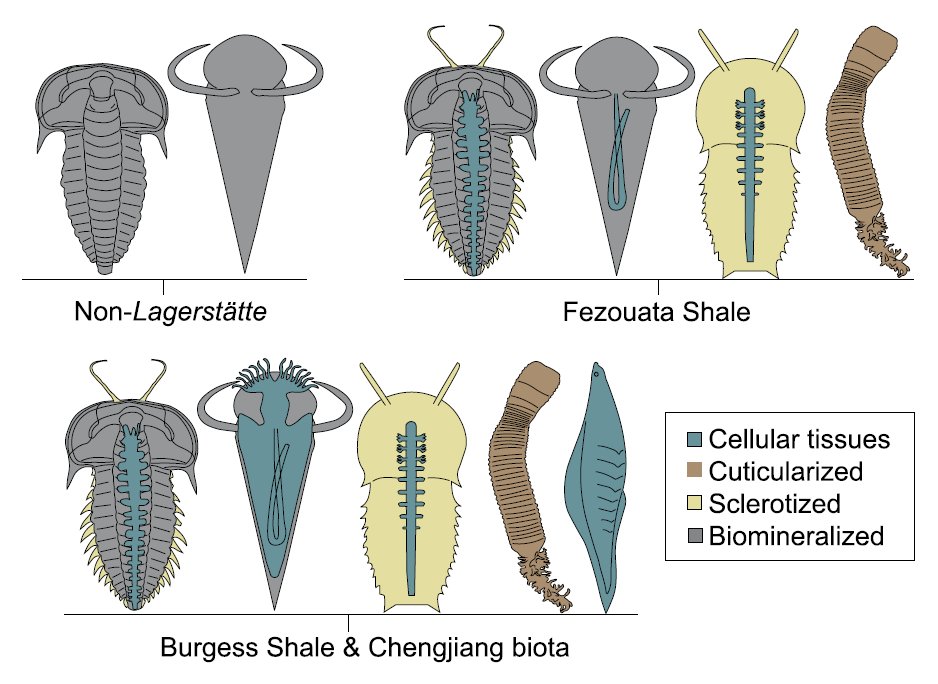

Now a newly discovered fossil site in Morocco may help to increase interest in the Ordovician period by highlighting the diversity of large arthropods that existed 470 mya. The site is a part of the Fezouata shale that outcrops from the Atlas Mountains and which has recently been designated as one of the 100 most important geological sites in the world.

The Fezouata shale as a whole is well known for the exquisite condition of its specimens, with the soft parts of the animals often as well preserved as their hard shells. However most of the specimens in the Fezouata consist of creatures that lived and crawled on the shallow sea floor. Until recently very few specimens of free swimming or nektonic animals had been found. The new site, which is being excavated by paleontologists from the University of Lausanne and the University of Lyon, does precisely that, providing specimens of dozens of new species of arthropod that swam freely, some of which are as much as 2m in size.

It is thought that the new site may be different from the already known Fezouata sites because the carcasses of larger animals where transported to deeper water by underwater landslides. Regardless the new site opens yet another window into a relatively unknown time in the history of life on Earth.

Another such window is the Berlin Ichthyosaur State Park in the state of Nevada. Unlike the Fezouata site in Morocco, which contains specimens of dozens of different species, the Berlin site is very much dominated by specimens of the bus sized ichthyosaur species Shonisaurus popularis.

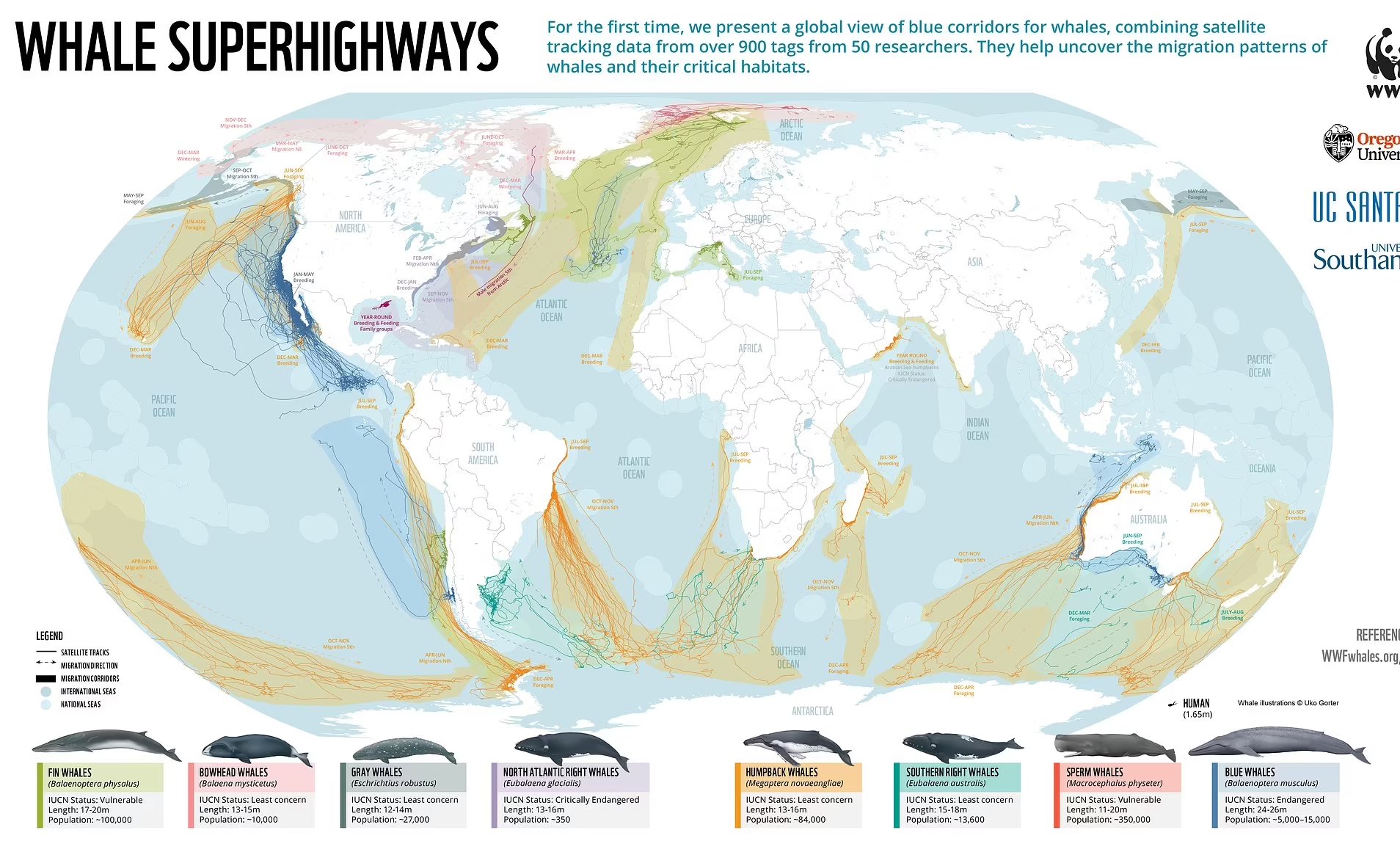

Living during the age of dinosaurs, ichthyosaurs were aquatic reptiles that seem to have filled the same ecological niche as dolphins, porpoises and whales do in the oceans today. In a recent issue of Current Biology a team of researchers from the University of Utah, the Smithsonian Institute, Vanderbilt University, The University of Nevada at Reno, the University of Texas at Austin, along with Vrije Universiteit in Brussels and Oxford University in the UK, have published a new paper that suggests that Shonisaurus popularis may have resembled whales in more ways than just size and shape.

In our modern seas several species of whales are known to migrate thousands of miles in order to give birth in relatively predator free, protected areas of the oceans. The researchers think that the Berlin site may have served the same function for the ichthyosaurs who ruled the seas back when dinosaurs ruled the land.

As I said above the fossils at the Berlin Ichthyosaur park are almost exclusively Shonisaurus popularis, there’s little sign of anything that the ichthyosaurs could feed upon, or feed upon them. The fossils also consist primarily of fully grown adults and newborns, no juveniles.

For a long time it was thought that the Berlin site may represent an ancient beaching, where a group of Shonisaurus popularis got confused and swam up onto a beach that they could not escape from, much as dolphins and porpoises do today. However a chemical study of the rock around the fossils shows no sign of any toxin that could have led to such a beaching. And a 3D analysis of the positions of the fossils indicates that the animals did not all die at the same time but rather over hundreds, if not thousands of years. In other words, occasional deaths happening at a place where large numbers of the animals gathered on a yearly basis.

So did ichthyosaurs, the whales of the age of dinosaurs also migrate across the oceans of their day to aquatic nurseries where they could give birth in relative safety? The Berlin site certainly suggests that they did and if so that would show that, when living creatures face the same problem they often evolve the same solution, even when separated by millions of years.

Finally another large scale study by paleontologists at the University of Oulu in Finland, the Universities of Leon and Vigo in Spain along with the University of Edinburgh in Scotland have tackled the question of why it was that the dinosaurs went extinct while some species of mammals, birds along with crocodiles and turtles managed to survive. The team of paleontologists carried out their investigation using the data obtained from hundred of different papers on environmental conditions at the end of the cretaceous period published over the last decades.

According to the study the answer may be, paradoxically that the dinosaurs were too dominate, too well fitted to the environment as it existed just before the asteroid struck. By adapting so completely to their world the dinosaurs had pushed the other creatures to the margins where they had to do whatever they could to survive.

That may have served the dinosaurs well before the asteroid struck, but in the environmental upheaval that followed they couldn’t adapt in time, while the small little rat like mammals managed to get by on whatever they could find. In other words the dinosaurs were so good at what they did that they couldn’t learn to do anything else while the mammals and birds had already learned to do many things making them better able to adapt to the new conditions.

A lesson perhaps for today with our, human induced, rapidly changing environment?