I don’t often discuss fossil plants very often in these posts, which is a mistake on my part because without plants using photosynthesis to convert sunlight into food there would be no life here on Earth. In this post I will be reporting on a very important plant fossil, one that pushes the age of a whole order of vital food plants back into the age of the Dinosaurs. With that in mind I will reverse my usual procedure of starting with the oldest fossils and going forward in time so that I can make Palaeophytocrene chicoensis the top story for this post.

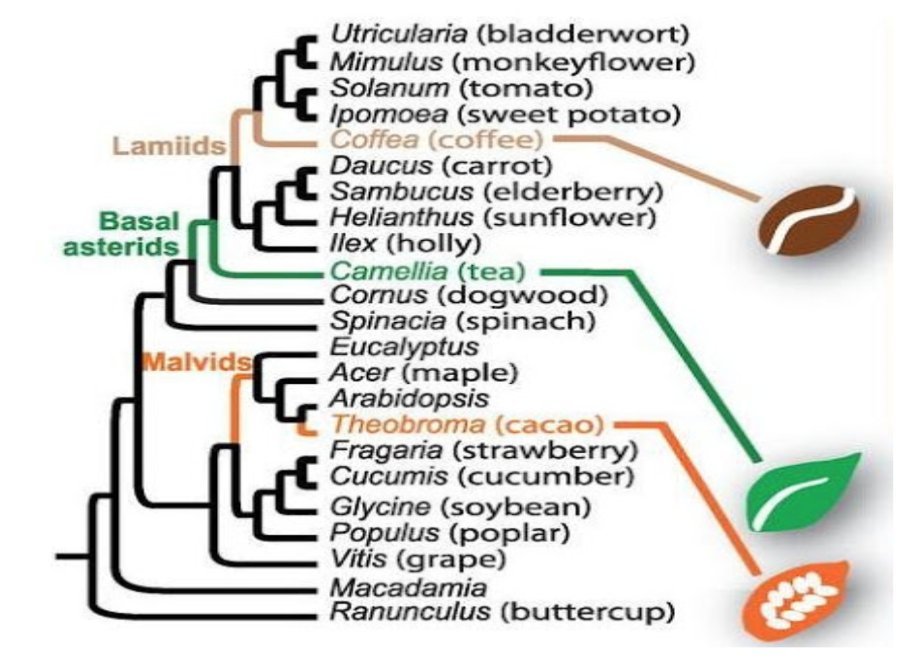

Everyone pretty much knows that there are three basic types of land plants; in order of when they first evolved there are the ferns, the conifers or evergreens and finally the flowering plants that are the type most familiar to us today. One order of the flowering plants are the Lamiids, a group of some 40,000 species and includes some well known and very important crop species such as the potato, tomato and coffee. The chief characteristics that the Lamiids share are a woody, vine-like structure that allow them to naturally inhabit rainforest type environments.

In the fossil record the Lamiids are a fairly diverse group that appears shortly after the mass extinction that ended the time of the dinosaurs. In fact the group is so diverse so shortly after the extinction that paleobotanists have long speculated that the Lamiids must have first evolved during the cretaceous period, the last period when dinosaurs still ruled. The smoking gun of an unmistakable Lamiid fossil from the cretaceous could not be found however.

Until now, for Brian Atkinson, assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Kansas has, after seven years of searching, succeeded in finding a Lamiid fossil from the cretaceous. The fossil has been given the name Palaeophytocrene chicoensis, the species name coming from the Chico Formation of cretaceous age about 80 million years ago in north-central California near Sacramento.

Professor Atkinson didn’t discover his Lamiid fossil in the ground however. As often happens Atkinson found the specimen lying unrecognized in a collection of fossils, in this case the collection of the Sierra College Museum of Natural History. The fossil was one of a number of specimens that were originally unearthed during the construction of a housing project near Granite bay in Sacramento during the 1990s by Richard Hilton and Patrick Antuzzi of Sierra College.

The instant that Professor Atkinson saw the fossil fruit Professor he was certain that it was the fruit of a Lamiid of the family lcacinaceae but like every good scientist the professor made a thorough examination using the latest technology. Based on his findings Atkinson finally assigned the specimen to the genus Palaeophytocrene, members of which are well known from the period shortly after the extinction.

The discovery of Palaeophytocrene chicoensis is important not only because of what it can tell us about the evolution of the Lamiids but also because of what we can learn from it about the way that ancient forests changed from being dominated by conifers to consisting mostly of flowering plants, one of the most critical ecological changes in the history of life. Palaeophytocrene chicoensis is yet another example, not just of how a single fossil can teach us so much but of how the ability to recognize something important, something other people don’t see, often leads to major discoveries that can change the world of science.

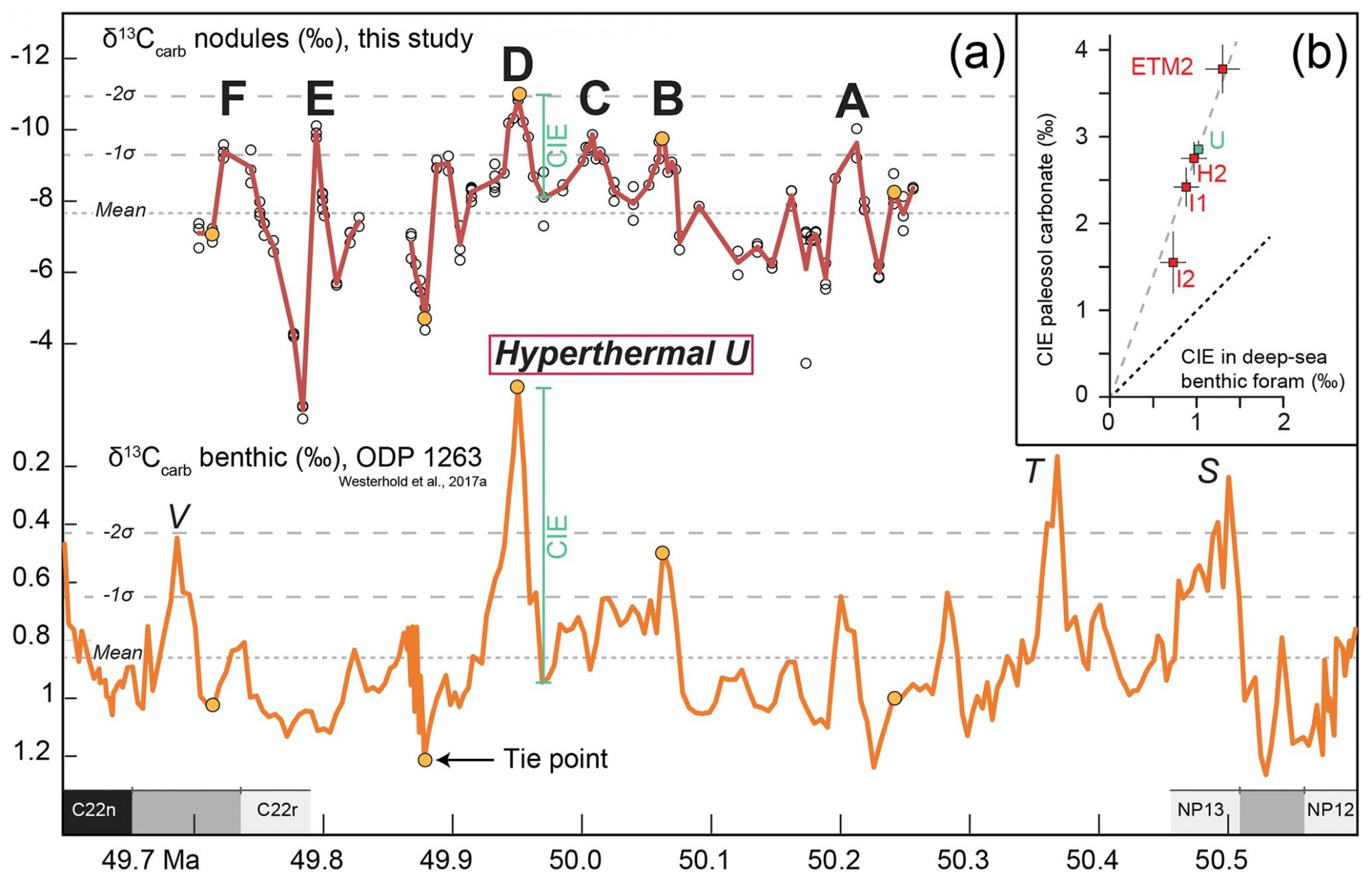

Giant insects are usually something out of a grade B movie from the 1950s. In reality Ants of the genus Titanomyrma may not have been as large as the ants in 1954’s ‘Them’ but with a length of as much as 10cm and a wingspan of 15cm they were certainly among the largest of their kind. Titanomyrma lived some 50 million years ago and specimens have been found in both Western Europe, England and Germany, and also in western North America, which is something of a puzzle to paleontologists. How did a genus of ant, big ones but still ants, get across the Atlantic ocean in order to populate both continents? At that time there was still a land bridge connecting Europe and North America but it was in the cold Artic, not the sort of environment ants prefer.

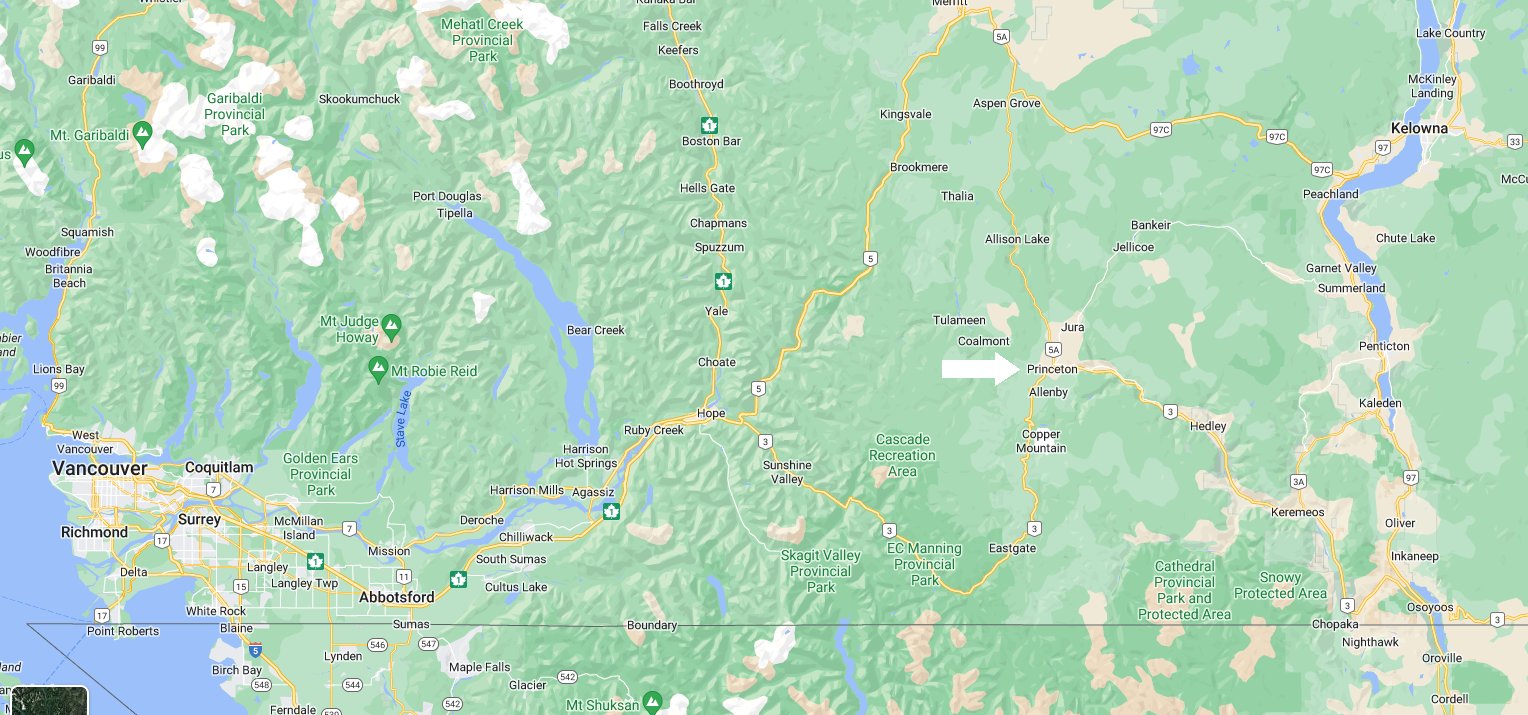

Now a new fossil specimen of a queen ant of the genus Titanomyrma has been unearthed outside the town of Princeton in British Columbia in Canada by an amateur fossil collector named Beverly Burlingame and is now being kept at the local museum. This specimen is the first of its kind ever found in Canada and the fact that Titanomyrma was found so far north is forcing researchers to consider the possibility that the ants did actually migrate through the polar regions.

It might not have been so cold however, nowadays we’re used to the idea of climate change and in particular a reduction in size of the polar ice caps due to a global temperature rise. The idea that brief periods of ‘Hyperthermals’ as they’re called could have allowed Titanomyrma to cross the Artic region is gaining evidence; indeed the fossil queen herself is now some of that evidence.

That’s how science works, specimens and evidence generate puzzles. More evidence then not only allows the puzzle to be solved but gives a more accurate, fuller picture of the whole system of which that puzzle was just a small part.