Many times in these posts I’ve discussed how at least 95% of the fossils that paleontologists, and amateurs collect are really just the hard parts of ancient animals, the bones and shells for the most part. The soft parts, the muscles, the inner organs, the skins are rarely preserved. Now to be sure paleontologists have become very good at figuring out what an extinct animal looked like, and how it lived from just the hard parts. Still whenever they find some trace of soft anatomy it’s a treasured discovery

Obviously some remains of the soft anatomy of an extinct animal is necessary to really understand it, without the impressions of feathers those fossils of archaeopteryx would just look like a small dinosaur. That’s why paleontologists get so excited whenever they come across a particularly important fossil with the soft parts preserved.

In this post I’ll be discussing two recent examples of how preserved soft parts are teaching paleontologists important facts about past life. As always I’ll talk about the oldest fossil first and move forward in time.

Arthropods are the most numerous and diverse form of animal life in our world today and have been pretty much since the first animals appeared over 500 million years ago. Think about it, all of the insects, spiders, and millipedes not to mention lobsters and crabs and barnacles are arthropods. The basic plan of a segmented body with jointed legs and an exoskeleton is without doubt the most successful way to build an animal.

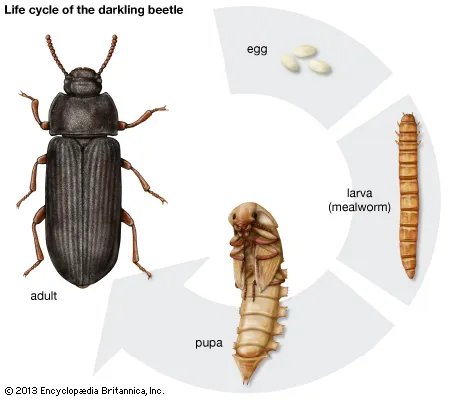

Yet despite all of the arthropod fossils that have been collected we still have a great deal to learn both about how arthropods evolved and how they grew at various times in the past. One thing to remember about arthropods is that very often their young don’t resemble the adults at all, think caterpillar and butterfly. Most arthropods go through various stages of growth as an egg, a larva, and pupae before becoming mature adults. Since larval stages of arthropod species can look very different from adults it is quite possible to mistakenly think that they are different species.

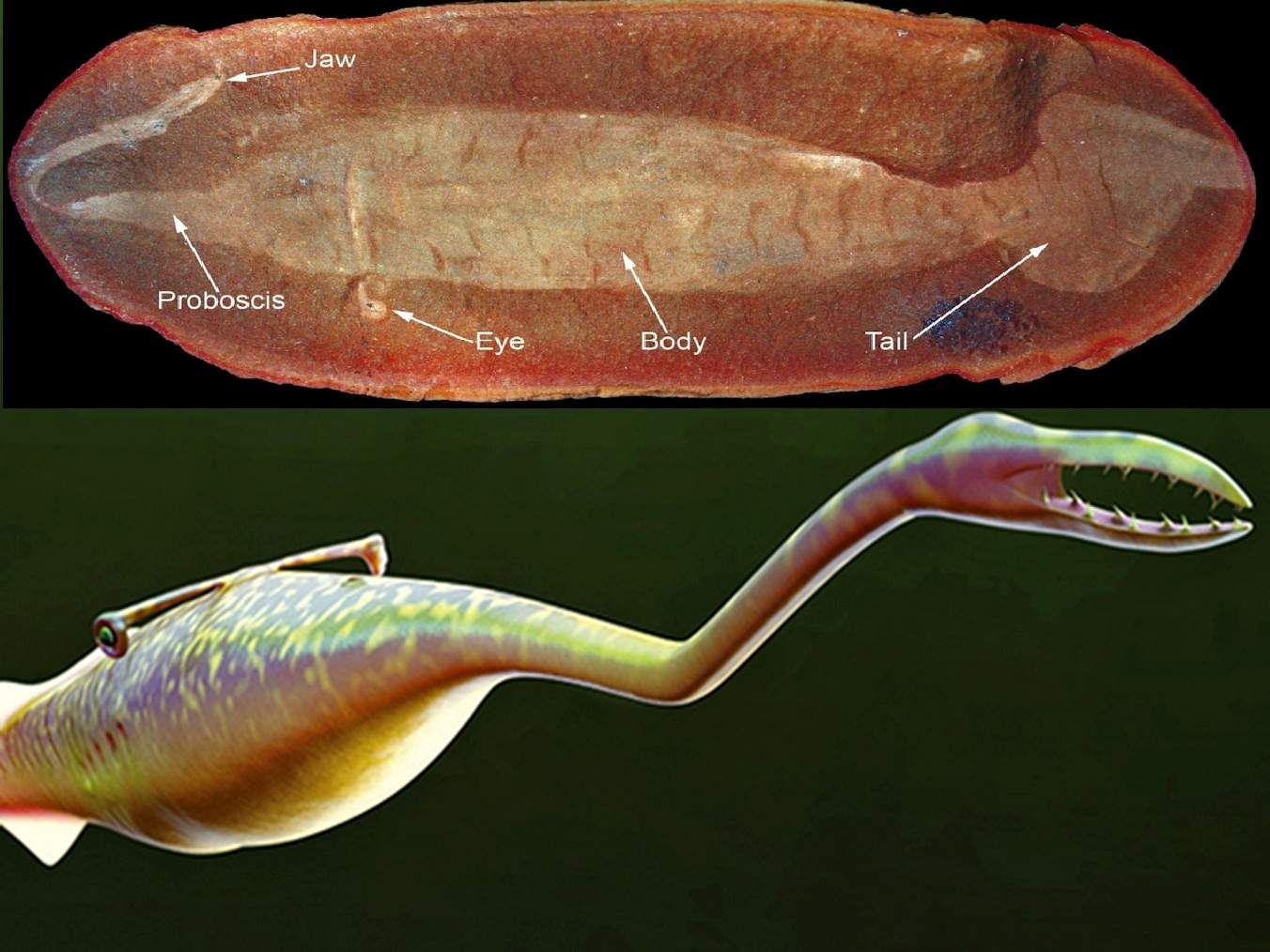

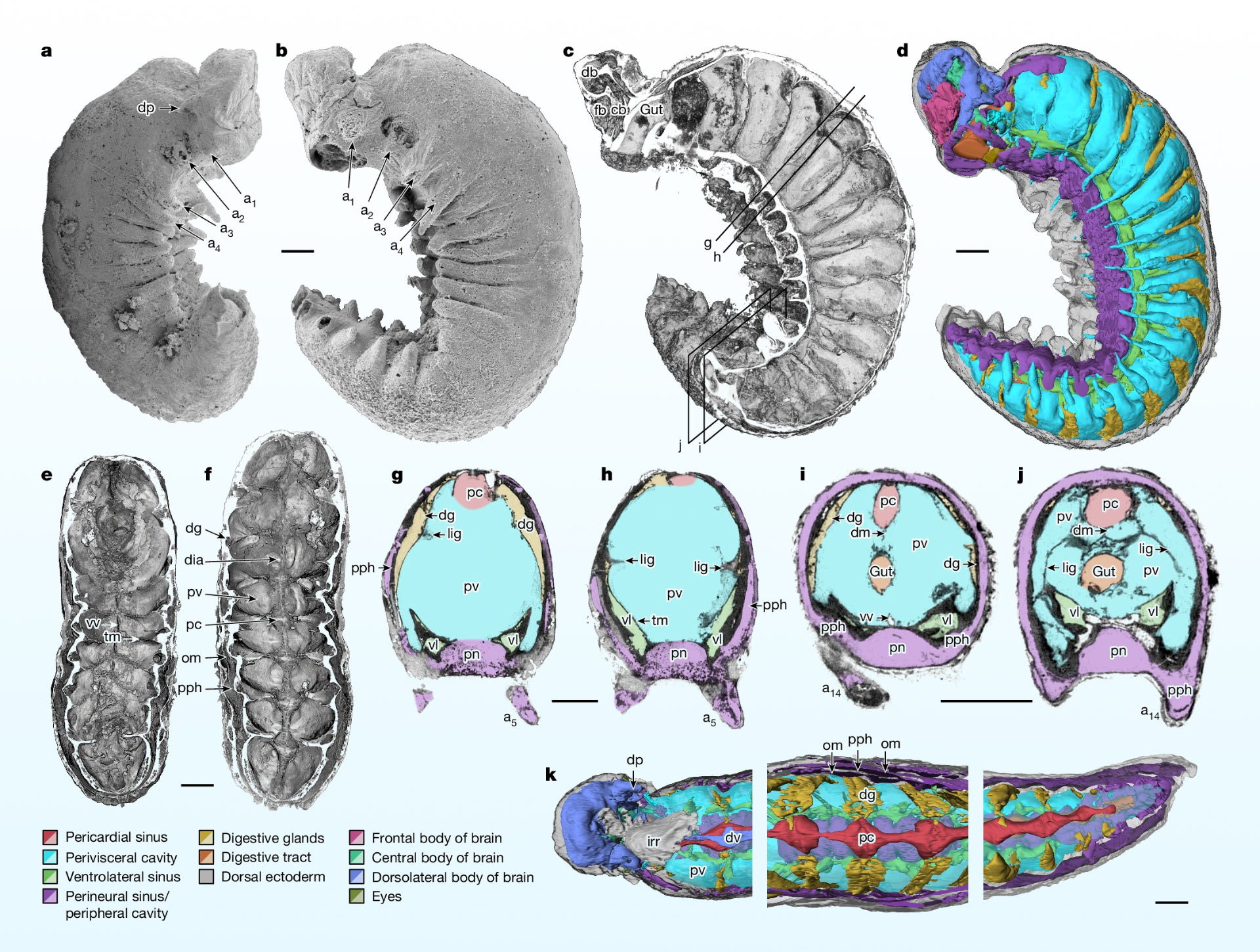

That’s why finds such as the 520 million year old specimen of Youti yuanshi are so remarkable. The small fossil, less than 4mm in length, somehow not only preserves virtually all of the soft parts of the larva’s anatomy but, unlike most arthropod fossils which are squashed flat, the specimen maintained its three dimensional shape. This enabled the researchers to reconstruct the internal arrangement of the animals organs. Not only muscle tissue but digestive organs were preserved along with traces of the circulatory system and even the presence of a ‘protocerebrum’, in other words a brain.

The specimen was found in the Yu’anshan formation in the Chinese province of Yunnan and has been described by paleontologists at Durham University and the University of Strathclyde in the UK along with Yunnan University in China. Best of all perhaps, at 520 million years old the specimen of Youti yuanshi comes from the Cambrian period, that time in Earth’s history when animal life was diversifying rapidly and the major groups of animal were becoming clearly defined. Because of this the specimen of Youti yuanshi can also tell us a great deal about the early evolution of what is perhaps the most important group of animals.

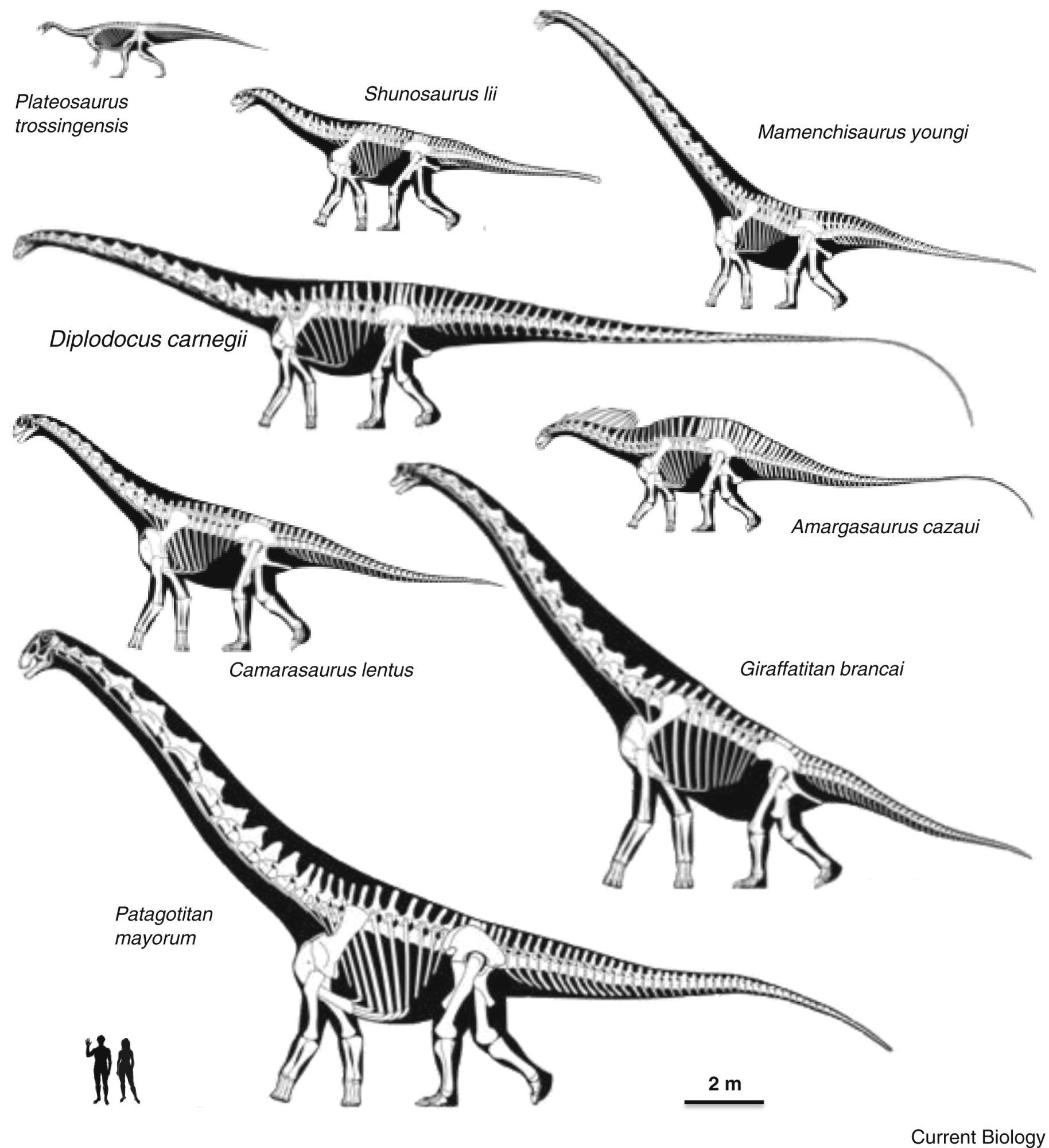

Let’s skip ahead now a couple of hundred million years to the age of the dinosaurs, in particular those long necked, long tailed sauropod dinosaurs that were the largest animals to ever walk the Earth. Now everyone knows that the sauropods were plant eaters, herbivores. Just looking at their massive, kinda awkward bodies and you can tell they weren’t predators chasing down or ambushing their prey. At the same time sauropods don’t possess any kind of offensive weapons like sharp teeth or claws that a predator would need.

The biggest land animals today, the elephants are herbivores, to grow so big an animal just has to eat and eat and eat, and that usually means plants, again that indicates that sauropods were plant eaters. One more thing, the teeth of sauropod dinosaurs are peg shaped, good for nipping off plant material but not good for tearing flesh.

Surprisingly however, there has never been any direct, conclusive evidence that sauropods are in fact herbivores. No fossilized fecal material or stomach material, technically known as coprolites or cololites, that are unquestionably associated with a sauropod specimen has ever been found. Until now!

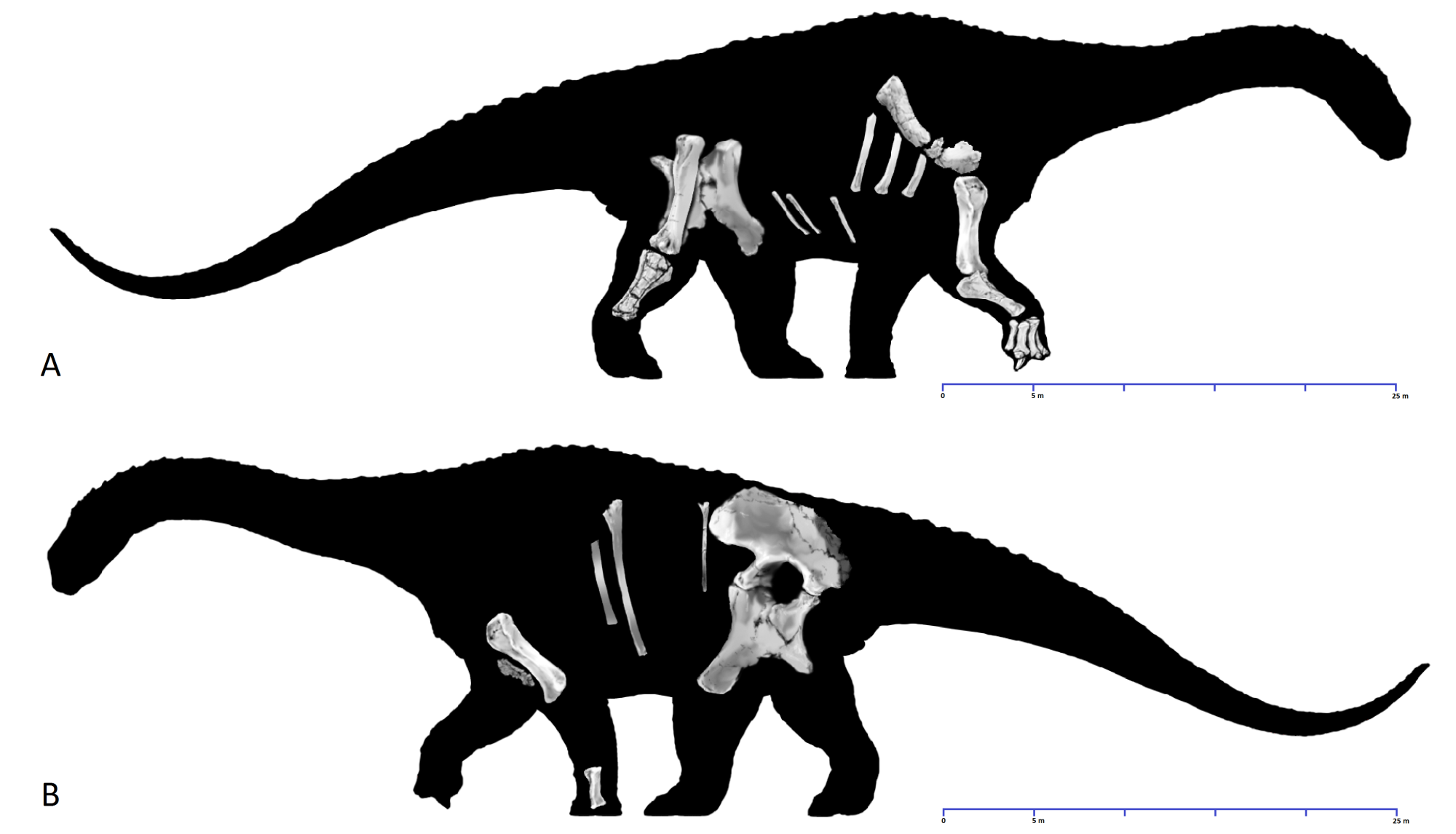

Recently a specimen of the sauropod Diamantinasaurus matildae was excavated from the Winton formation in Queensland, Australia. Dated to between 94 and 101 million years ago the animal was a ten-meter long juvenile. As the researchers from Curtin University and the University of Melbourne, both in Australia, were removing the animal’s bones they came across a mass of fossilized plant material right where the animal’s stomach would be.

Wanting to be absolutely certain the paleontologists carefully examined the area around the plant material and found impressions of skin both above and below the plant fossils, the material was indeed the contents of the animal’s stomach when it had died. Using the latest technology the paleontologists were even able to determine the types of plants D matildae had been eating before it died, while tall conifers seemed to predominate there was still evidence of recently evolved flowering plants, which at that period would have grown closer to the ground.

One thing that was clear from examining the cololites was that the plant material had been barely chewed, unlike the stomach contents of a modern cow that continuously chews its cud in order to break down the tough plant fibers. It appears that this sauropod at least simply bit off large amounts of leaves and then swallowed them.

Presumably, once in the sauropod’s stomach gut bacteria would have gone to work reducing the plant fibers to a digestible mass. In other words the stomach of this sauropod was something like a fermenting vat for beer or whiskey. Now this is just one specimen of the many species of sauropod dinosaur, just one data point, so other sauropods may have chewed more. Still we have finally unearthed conclusive evidence that sauropods were plant eaters, and we now know something of just how they ate and digested their food.

There are still many questions about the history of life on this planet, but with every discovery we learn a little bit more. The fun is in the discovery and learning.