I’ve come across three stories recently that illustrate nicely not only the wide diversity of life here on Earth but how much more there is for us to learn about it!

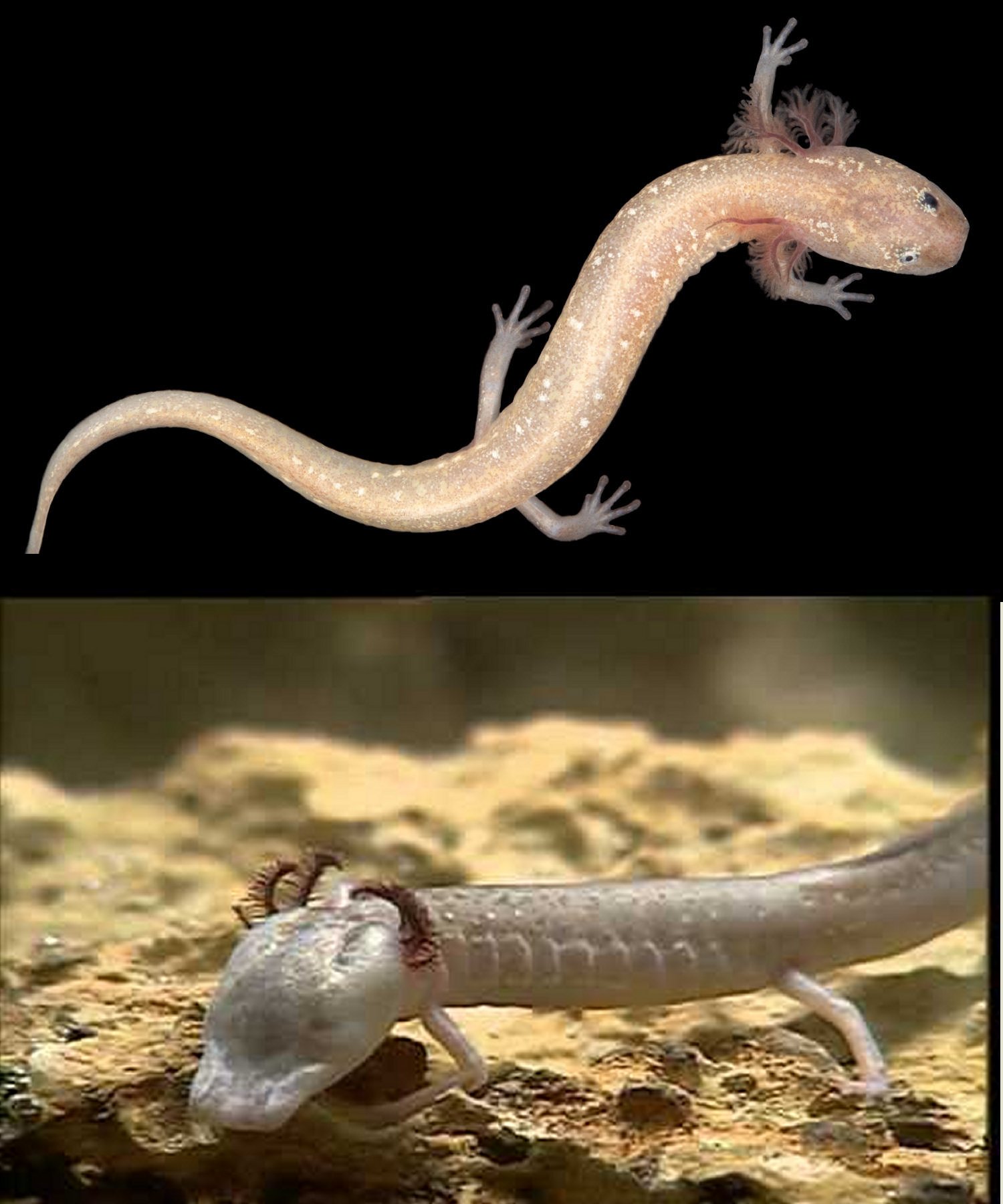

I’ll start with what is probably the most familiar type of animal, and location, salamanders in Texas. A team of naturalists led by Tom Devitt, an environmental scientist with the City of Austin’s watershed protection department, has recently discovered three new species of salamander.

Now most of Texas is dry and rocky, not the sort of environment you think of when you consider amphibians. However running through the south central portion of the state is the Pedernales River and the porous limestone bedrock of that region is crisscrossed with a network of caves and flooded channels known as the Edwards-Trinity aquifer system.

This system is the home of a wide variety of subterranean aquatic species. Many of these creatures are the descendants of ocean living creatures that inhabited the region in the cretaceous period when Texas lay at the bottom of a vast inland sea that stretched as far as the Canadian border. See map below.

Like many types of cave dwelling animals the salamanders discovered by the naturalists are very pale in colouration, lack eyes and possess flattened heads. Searching the twists and turns of these caves and channels isn’t easy so it understandable that these three small animals could have remained unknown for so long. Indeed it is quite likely that other species are still there waiting to be found.

The creature in our second story is probably not as familiar to most people as salamanders are. They are known as Hagfish and are one of the most primitive forms of vertebrates. Hagfish are such ancient creatures that their skeletons aren’t even made of bone but like sharks and rays they are composed of cartilage. Unlike sharks however, hagfish don’t even possess jaws but instead rely on a raspy tongue to scrape away at their food.

Hagfish are best known for possessing a remarkable defense mechanism that protects them from large predatory fish like sharks. Any creature that tries to take a bite out of a hagfish gets a little ball of mucus in their mouths that in less than a second expands about 10,000 times in volume, choking the hagfish’s attacker and allowing the hagfish to escape!

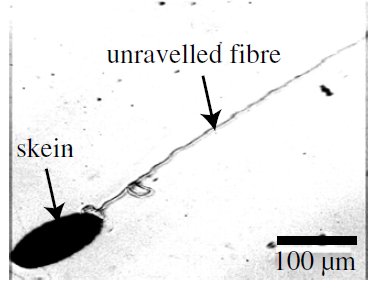

Scientists have been interested in the hagfish’s mucus for a long time, any material that can expand so much so quickly will certainly attract a good deal of attention. What scientists learned was that the most active part of the mucus is a very large number, many thousands of tightly coiled threads called skeins. See image below.

An individual skein measures only about 100 μm in diameter but once the thread is unraveled it can measure as much as 10cm in length, which accounts for the great increase in size of the mucus. See image below. Despite all that scientists had learned however the speed with which the threads unraveled remained unexplained. Speculation was that some unknown chemical reaction was responsible.

Now however Gaurav Chaudhary and Randy H. Ewoldt at the University of Illinois’ department of Mechanical Science and Engineering along with Jean-Luc Thiffeault at the University of Wisconsin’ department of Mathematics have determined that the hydrodynamic motion of the water itself is sufficient to uncoil the skein without the need of any chemicals.

Doctors Chaudhary and Ewoldt began by undertaking a detailed and precise examination of how the skein unravels while Doctor Thiffeault concentrated on the mathematics of the interactions between the uncoiling skein and the agitation of the water. Computer simulations indicate that nothing more than turbulence can result in the full expansion of the mucus.

Understanding the mechanics of a material that can expand thousands of times in volume could be of great importance in many engineering problems. The future will show if the hagfish’ defense mechanism can be reproduced and applied by human engineers.

My final story deals with a very common, yet small and largely unfamiliar creature formally known as Chaetognaths (The word means Bristle Jaw) but more commonly referred to as Arrow Worms. See image below. Living in environments ranging from brackish water to the floor of the ocean depths Chaetognaths comprise some 120 living species of predatory worm ranging in size from 2 to 120 mm.

Biologists have long been puzzled by Chaetognaths, unable to decide exactly where on the tree of life their small branch lies. Traditionally arrow worms had been placed near the flatworms, segmented worms and molluscs but in fact there was even debate as to which supergroup of animals the Chaetognaths belonged, the protostomes or the deuterostomes.

Now both protostomes and the deuterostomes share a common body plan with a single intestinal system running through them. The difference lies in which opening forms first, in protostomes the mouth forms before the anus while in deuterostomes it is the anus that forms first. Vertebrates are protostomes by the way while insects are deuterostomes.

To clear up the mystery a group of biologists from around the world led by Ferdinand Marle’taz of the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) Molecular Genetics Unit have completed a detailed studied of ten species of arrow worm and compared them to other animals.

The results of the study clearly showed that Chaetognaths belonged with in protostomes but were not closely related to the other worms or molluscs. The closest relatives to arrow worms appear to be the tiny, often microscopic freshwater animals known as rotifers. See image below.

While the study by Doctor Marle’taz and his colleagues appears to have resolved some of the mystery of arrow worms there remain plenty of other questions to be answered as we learn more and more about the other creatures with which we share our world.