We’re all familiar with the group behavior of animals. Whether it be a big herd of Bison, a large flock of birds or a huge school of fish we’ve all wondered how so many individuals without the ability to talk to one another can coordinate their movements so precisely that the group can sometimes seem like a single living thing.

Scientists have been studying this phenomenon for a very long time, even the ancient Greeks thought about the problem. We’ve succeeded in learning a great deal in the past few decades but some of the mystery still remains.

There are several reasons why a large group of animals, almost always of the same species and often of the same size and age, would come together to form a herd, flock or school, henceforth I’m just going to call it a group if you don’t mind. Increased success in both foraging and finding a mate are two reasons but predator avoidance is probably the chief reason.

You see first of all being in a large group means that there are just more eyes keeping watch for predators so there’s much less chance of bring surprised by one. Then, when a predator does attack having a score or more prey scatter in every direction overloads the predator’s senses, confusing it so that it is more likely to miss completely.

So once a large number of animals decide to become a group how do they actually do it. Well back in 1986 a biologist named Craig Reynolds was able to model much of group behavior by assuming the animals in the group obey three simple rules.

- Move in the same direction as your neighbor.

- Remain close to your neighbors.

- To avoid collisions don’t get too close to your neighbors.

Just what close and too close mean depends on the species and remember these rules have been imprinted onto the individuals by evolution. In other words they’re not thinking about it they just feel happier with some company but also a little room as well.

O’k, so now everybody’s moving in a group, so who now decides in which direction the group is going to go? Well since many of the species that form large groups are migratory on a large scale everybody instinctively knows the general direction to go! It’s spring so everybody knows that they’re supposed to go north, or the leaves are falling so aren’t we all supposed to fly south.

Of course that doesn’t help when it’s dinnertime and hopefully somebody knows where to find some food around here. In that case the more experienced members of the group seem to take charge and lead the way to food sources that the group used on the last migration, some such resources have been used for thousands of migrations. There is also a controversial idea that it is the hungrier members of the group who take charge after a long days travel.

Once a few members of the group start to head in a certain direction the others employ a simple quorum rule to ‘follow the leader’ until everybody is heading the same way. Usually this decision making process results in the correct choice for the group but occasionally it can cascade into exactly the wrong choice, we’ve all heard of beached whales and lemmings after all.

These decision making processes are called collective intelligence and in many ways it is the speed with which the group coordinates its actions that seems almost magical. Such speed obviously requires each individual to have fairly accurate idea of where at least its nearest neighbors are.

Vision of course is an important means of knowing where everybody else is. Now however a team of researchers at New York University’s Courant Institute of Mathematical Science has published a paper detailing that for fish and birds the ability to sense the wake left behind by the leaders also plays an vital role. “Air or water flows naturally generated during flight or swimming can prevent collisions and separations, allowing even individuals with different flapping motions to travel together.” According to Joel Newbolt, lead author of the study.

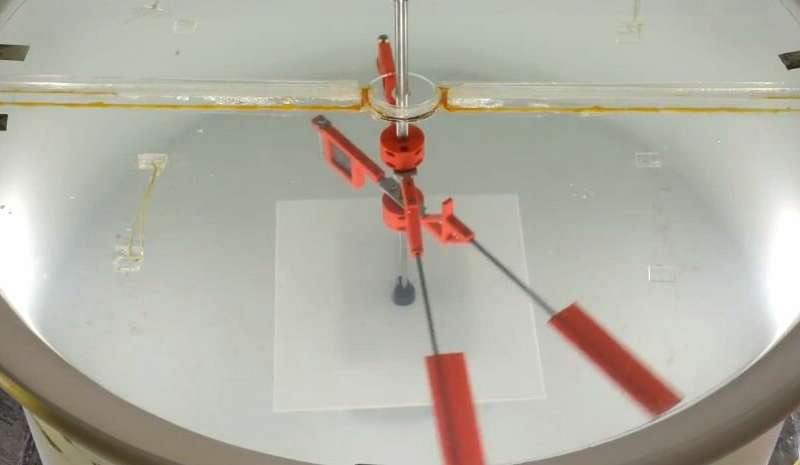

The study used a robotic ‘school’ of two hydrofoils that flap up and down and swim forward, see image below.

What they found was that the trailing flap could most efficiently swim along if it ‘surfed’ in the wake of the lead flap, maintaining just the right distance between them. This is similar to the way geese fly in a Vee formation so that trailing birds get a boost from the air currents produced by the birds ahead of them only now the wake is being used to keep the right distance between individuals.

We still have a lot to learn when it comes to the phenomenon of collective intelligence in herding animals but we are making progress in our understanding of how some species have evolved to act together for the good of everybody. If only we humans could learn that lesson!