This is the second installment of what I plan as a series of articles leading up to the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 and humanity’s first landing on the Moon. In these articles I will reminisce about some of the most important milestones on the journey that led to Apollo 11, some of the best known events in the Space Race.

In the first installment I discussed how the Soviet Union had surprised the USA by successfully launching the first artificial satellite just months before America had planned on doing so. Then when America’s Vanguard satellite blew up on the launch pad in front of the entire world the US was left playing catch up even though the satellite they finally launched, Explorer 1, made the first important discovery of the space age, the van Allen radiation belts encircling the planet.

So with the first satellites launched into orbit the race was now on to see which country could be the first to put a man into space. Once again the Americans conducted their preparations in the full blaze of publicity. With considerable fanfare the new National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) announced project Mercury and on April 9th 1959 the world was introduced to the Mercury Seven Astronauts, see image below. The Mercury astronauts were all military jet pilots who were considered to be the best suited to undergo the rigors of space travel.

Once again the Soviets carried out their preparation in total silence, not even publicly admitting that they were working on a manned space program. Indeed the very name of the chief engineer of the Russian space program, Sergei Korolev, the designer of their huge R-7 rocket, was kept an absolute secret. Like the Americans the Soviets choose military pilots to be their cosmonauts, twenty men were selected during late 1959.

While the training that all these men underwent was arguably the most exhaustive in human history the medical examinations were actually far worse. No one knew how the human body would react to the environment of space, in particular zero-gravity. There were in fact many well recognized medical experts who maintained that zero-gee would kill within minutes, a person’s heart would race uncontrollably or you would be unable to swallow and the build up of saliva would choke you. Both manned space programs were determined that if any human being could survive in space their astronauts could.

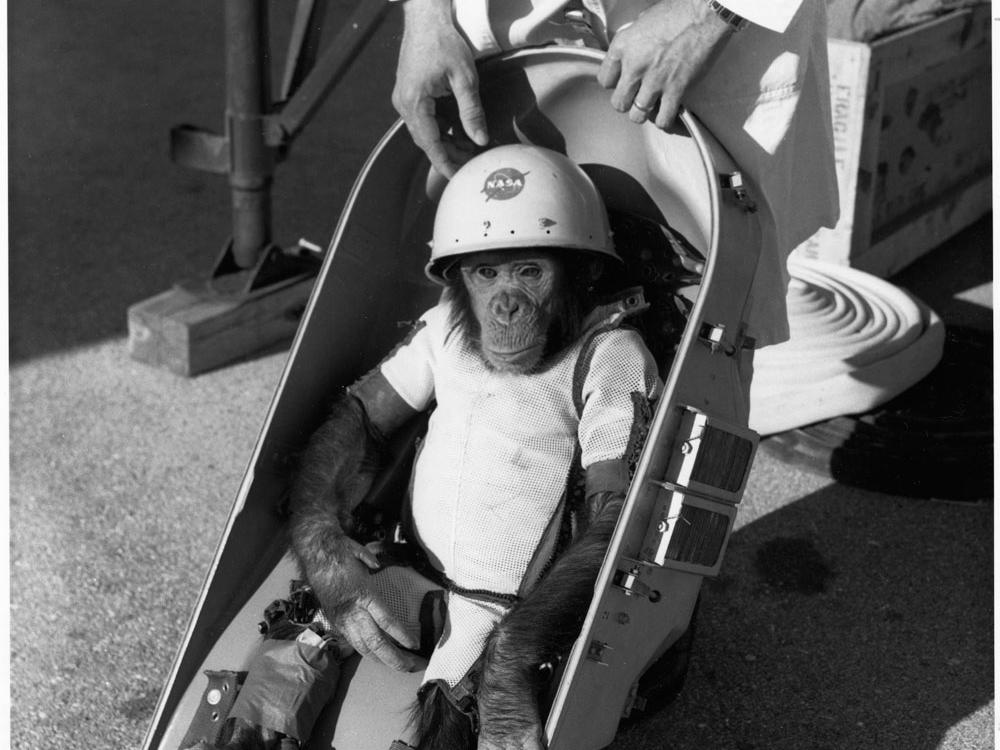

NASA chose to progress cautiously, step by step. They began with unmanned launches of their Mercury capsule before then proceeding to the launch of a young chimpanzee named Ham. All before considering a manned flight.

The Mercury capsule was designed as the smallest possible system that could support a single human being for one day’s time. Basically conic in shape the capsule was 3.3 m in height and 1.8 m wide at its base with a mass of less than 1400kg. The astronaut lay inside facing the top, which was found to be the best position for withstanding the high-gee forces of launch. See image below.

The bottom of the vehicle was fitted with retro-rockets to bring the craft out of orbit along with an ablative heat shield to remove the heat caused by the fiction of re-entering the atmosphere. Once friction had eliminated most of the Spacecraft’s velocity parachutes would open to bring the capsule to a landing in the ocean.

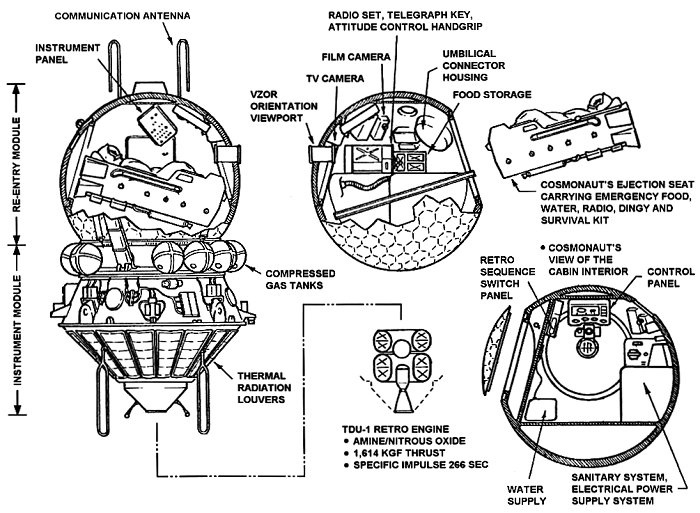

Meanwhile the Soviet chief designer was working on the plans for his Vostok space capsule. Sergei Korolev had a big advantage in that his R-7 rocket was simply capable of putting more mass into orbit than anything the Americans had or would have until the mid-1960s. This allowed him to follow typical Russian engineering practice and develop a simple, strong and sturdy spacecraft.

The Vostok spacecraft consisted of two modules, a spherical crew compartment 2.3 m in diameter weighing 2400kg along with a service module about a half a meter wide by 2.3m in diameter weighing 2300kg. With its larger size the Vostok capsule was capable of sustaining a cosmonaut in space for a longer period of time, up to five days.

The entire surface of the Vostok crew capsule was covered in ablative material for re-entry. An unusual feature of the capsule was that, as it descended on parachutes to a landing on land, the cosmonaut was expected to leave the capsule and parachute separately to the ground.

Once again it was the Russians who succeeded first, launching Yuri Gagarin into a single orbit flight lasting about ninety minutes on the 12th of April in 1961. Once again the USSR had scored a space first just days before the US was ready for their flight. Alan Shepard became the first American in space just three weeks later on the 5th of May on a suborbital flight lasting about 15 minutes.

Not only had the Soviet’s succeeded first but they had placed a man into orbit while the American’s were not only second but were still conducting suborbital flights. It would be another eight months before John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth on February 20th of 1962.

In the end both the Vostok and Mercury programs carried out six successful manned launches. Between them the two programs demonstrated that human beings could survive, and even carry out some tasks in space.

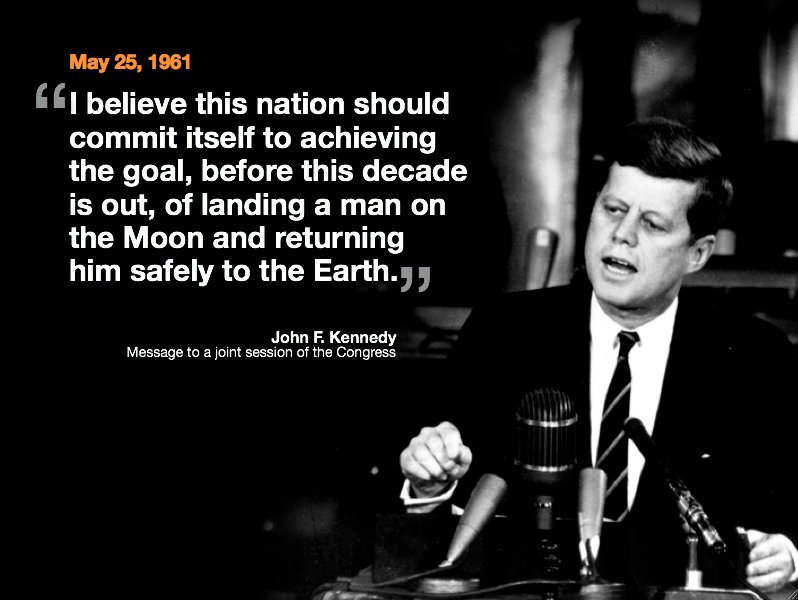

America was still in second place, and there seemed little that NASA could do in the short term to take the lead. It was as much to distract his countrymen from their current subordinate position that President John F. Kennedy decided to challenge NASA with a long-term goal that would tax American science and industry to their fullest.

On May 25 1961, before a joint session of both houses of congress Kennedy declared. “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth.”

The space race now had a finish line. Only time would tell which nation, if either, would get there first.