A couple of new discoveries have recently been published about the ancient and extinct sea creatures known as trilobites so I thought that this would be a good opportunity to discuss these fascinating creatures in some detail. I’ll begin with a few general facts about trilobites.

First of all trilobites are members of the phylum arthropoda, the jointed limbed animals that include crustaceans, insects and spiders. In fact trilobites are generally recognized as the earliest members of that group of animals with fossils going back as far as 540 Million years ago. Trilobites not only evolved a long time ago they also went extinct a long time ago. The last trilobites died in the Permian extinction event about 250 million years ago, see my posts of 16 February 2019 and 2 June 2018. That’s several million years before the first dinosaur ever evolved!

Because trilobites lasted so long, and their exoskeleton fossilized so easily paleontologists have been able to identify more than 50,000 different species. During their almost 300 million year existence trilobites evolved to occupy nearly all of the ecological niches occupied by modern marine arthropods including that of scavenger, predator, filter feeder and even a swimming species that fed off of the plankton near the surface.

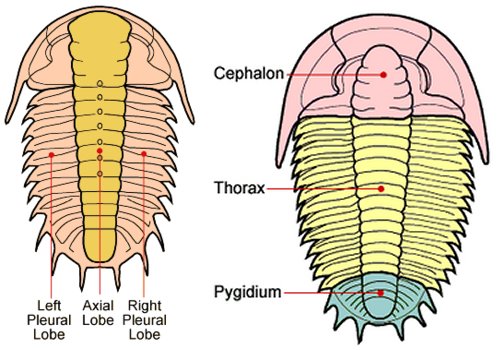

Looking at the figure below, you can see that Anatomically trilobites are defined by their broadly oval shape and the three main sections of their body going side to side, right pleural lobe, axial lobe, which is often raised, and left pleural lobe. Many people incorrectly think that the three lobes of the name trilobite refer to the three sections going front to back with the cephalon (head), thorax and pygidium (tail). (I did when I was young!)

Early trilobites, such as Olenellus from the Cambrian period seen below, had a cephalon that was much larger than their pygidium. As trilobites evolved however their tails grew to almost the same size and shape as their head as seen below in Phacops from the Devonian period. This adaptation allowed later trilobites to roll up into a protective ball in much the same way as a modern armadillo does. Fossils of such rolled trilobites are often found in Devonian, Mississippian and Pennsylvanian rocks.

With a history of 300 million years and at least 50,000 species trilobites varied considerably in their particulars, especially size and ornamentation, see images below. The largest known trilobites are from the genus Isotelus of the Ordovician period some 450 million years ago specimens of which are as long as a meter. There are a number of candidates for the smallest member of the group but many small trilobites were no larger than a pea.

For the most part however trilobites remained rather conservative in their basic body plan. This may have contributed to their eventual extinction as competitors such as crustaceans and fish evolved structures like jaws and manipulating pincers that allowed them to outperform the trilobites.

As fossils a complete trilobite is fairly rare, one or two can represent a good day’s hunting. On the other hand recognizable pieces of trilobites are very common. The reason for this is that like all arthropods trilobites had to molt in order to grow. So a single live trilobite could in the course of its life produce many empty shells that would quickly break up to produce a lot of trilobite pieces.

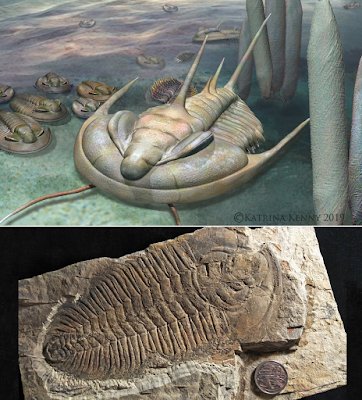

A couple of recent studies have further increased our knowledge of these ancient creatures. The first concerns the discovery of a new species of trilobite from Australia that has been named Redlichia rex. The name is a reference to the well known dinosaur Tyrannosaurus rex because of R rex’s large size, 30cm, and leg spines that could be used to crush the trilobites food. The fossils of R rex come from the Emu bay shale of Australia’s Kangaroo island and are exceptionally well preserved revealing details of even the animal’s delicate antenna, see image below.

Because of R rex’s large size and crushing legs it is believed that the trilobite was a predator, and perhaps even a cannibal. Specimens of R rex have been found with healed injuries so the question is, what could have preyed on these large, for the Cambrian period, animals. While there are several possibilities it has also been suggested that R rex may have preyed on its own kind!

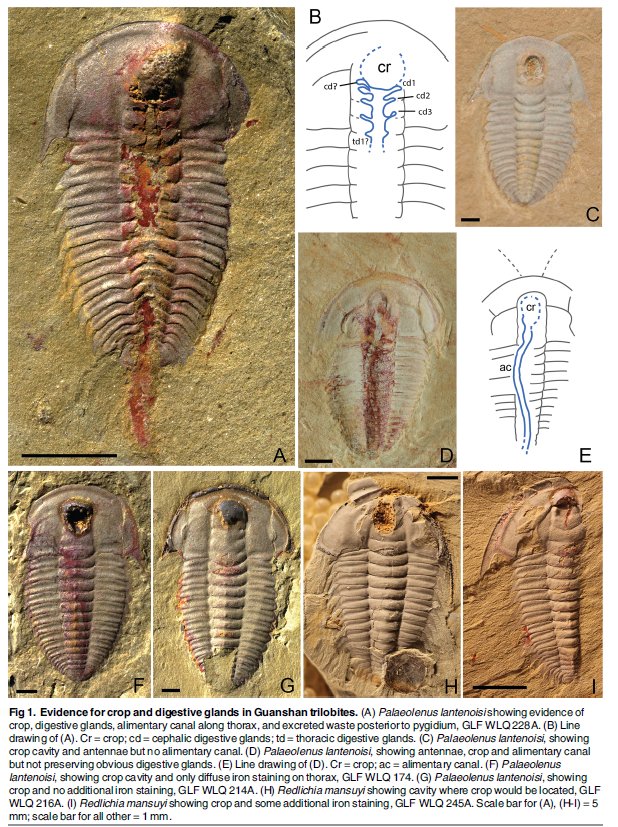

The second discovery also comes from a fossil site that is well known for exceptionally well-preserved specimens, the Guanshan location in eastern Yunnan province China. In this study it’s not a new species of trilobite that’s been announced, it’s the discovery of the earliest known evidence for a stomach and digestive system!

Using some of the best specimens of the trilobite Palaeolenus lanteroisi, see image below, researchers from the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Early Life Institute at Northwest University in Xi’an China actually succeeded in ‘dissecting’ the fossils. That is, they have managed to carefully remove a portion of the upper layers of the fossil in order to examine the petrified remains of the animal’s internal organs.

What they found was a well-developed digestive system with a large stomach or ‘crop’ in its cephalon. That’s right trilobites appear to have had their stomach’s in their heads not far from their mouths! A long alimentary canal then went through the length of the rest of the trilobite’s body to an anus at the animal’s posterior. Trilobites have a special place in the history of life, as one of the first complex, multi-cellular forms of animal they dominated the ancient Cambrian and Ordovician seas. Thereafter they gradually declined, finally becoming extinct during the Permian catastrophe. Nowadays for any fossil hunter a good trilobite specimen will always be a small prize to be treasured.