We’ve all heard stories about how the frozen remains of Wholly Mammoths are sometimes found in near perfect condition in the cold artic tundra of Siberia. Well its not just Mammoths that have been discovered, reindeer, bears even artic hares and foxes are occasionally found there.

Now a new and potentially very important find has been made along the Indigirka River, northeast of Yakutsk, considered the world’s coldest city. The find made by Doctor Sergey Fedorov of the Institute of Applied Ecology at Russia’s North-Eastern Federal University is that of the frozen corpse of a puppy and the biggest new may be that so far scientists can’t decide whether it’s a dog or a wolf. The remains have been given the name Dogor which in the local Yakut language means ‘friend’ but the English pun of ‘Dog or ?’ was intentional.

From an initial examination Dogor was a male and appears to have been about two months old when he died. When samples of Dogor were radiocarbon dated they were found to be 18,000 years old but after DNA sequencing was performed at Sweden’s Centre for Palaeogenetics the scientists were unable to decide whether Dogor was a dog or a wolf. That is despite the centre having Europe’s largest bank of DNA samples of canines from around the world to use as comparisons.

Of course the most exciting result would be if Dogor turned out to be neither a wolf nor a dog but a transition between them. We all know that wolves were the first animals to be domesticated by humans, becoming dogs in the process, and if Dogor is an example of that transition then he may be able to tell us quite a bit about how humans first came to domesticate wild animals.

Which begs the question, what do we know about when, where and how humans turned wolves into dogs?

I remember fifty or more years ago the leading theory for wolf-dog domestication was that about 20,000 years ago, probably somewhere around the Ural Mountains in Russian, a band of hunter gatherers killed some adult wolves and then came upon the wolves’ now orphaned pups. Rather than killing the pups the humans decided to make pets of them and when the pups grew up the humans practiced selective breeding, that is only allowing those pups we liked to breed. After several generations the wolves would have become tame, the first step in becoming a dog.

The problem with that scenario is that wolves are wild animals and even if raised from pups when they grow up they will be much too difficult to handle. This same thing is true of chimpanzees; people often buy baby chimps as pets only to have to get rid of them when they grow up because adult chimpanzees are just too big and strong and wild to be a good pet!

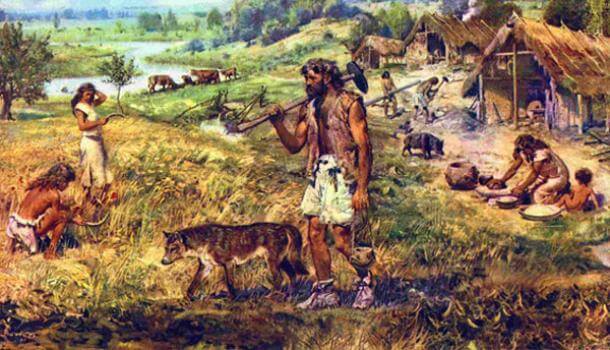

So how did wolves ever become tame enough so that humans would ever even consider taking them in as pets? The current thinking goes something like this. Twenty thousand years ago or so, as groups of hunter gatherers feasted on their kills and other foods they would throw their waste onto nearby garbage piles, paleoarcheologists have found the remains of some of these garbage dumps by the way. Those garbage piles attracted scavengers, wolves among them and those wolves who were the least afraid of humans got the most of the leftover food scraps.

In time some wolves might even begin to follow the humans as they moved from one campsite to another, hunter gatherers are nomadic after all. Over several generations the wolves would become more dependent on humans, and the humans would become used to having the wolves around, perhaps even using the wolves as proto-watchdogs. How long this process may have taken is unknown but there is evidence that it actually may not have taken very long.

That evidence comes from an experiment that began in 1959 in the old Soviet Union. In Russia the breeding of animals for their fur is a big industry and zoologist Dmitry Belyayev thought that he could use a farm for raising foxes as a place to study the process of domestication by selective breeding.

Doctor Belyayev proceeded by separating the foxes on the farm into three classes. Those foxes that either fled from humans or behaved aggressively were placed in Class III while those in Class II neither avoided nor encouraged human contact. Class I was reserved for those foxes that showed signs of friendliness towards their handlers. The animals in Class I were then only allowed to breed with other Class I animals.

By the sixth generation Belyayev was forced to create another category, Class I Elite for those animals that actively sought human contact. What’s more the ways in which the Class Ie animals tried to attract their handlers was remarkable similar to a dog’s behavior, tail wagging, whining and licking hands and faces.

There were also actual changes in the fox’s physical morphology, their snouts became shorter and rounder, their skulls became wider. Even their ears changed, becoming floppy like a dog’s instead of pointing stiffly upward like a wild fox’s, and a wolf’s.

Doctor Belyayev’s experiment is still continuing although it is now being conducted by Doctor Lyudmilia Trut of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics in Novosibirsk. Doctor Trut was a graduate student of Doctor Belyayev and the two worked together for many years.

Thanks to the work of researchers like Doctors Belyayev and Trut along with the discoveries of Doctor Fedorov and the scientists at Sweden’s Centre for Palaeogenetics we are learning a lot more about where, when and how the dog first became man’s best friend.