Without our Sun life here on Earth would be impossible, we all know that. The Sun’s light not only keeps our planet warm but through the process of photosynthesis generates the food we need to survive. Recognizing this importance for centuries now scientists have examined the Sun with every instrument in their possession. However the very energy that the Sun produces can make it difficult to study. After all, if you get too close you could suffer the same fate as Icarus.

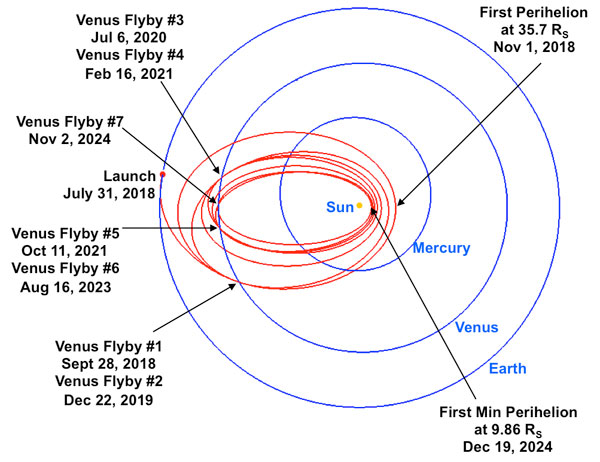

NASA’s Parker Solar probe is the space agency’s latest attempt to get up close and personal with our parent star. Launched back on August 12th of 2018, see my posts of 7 June 2017, 5 September 2018 and 3 November 2018, Parker is designed with a special ‘heat shield’ to protect its delicate instruments from being destroyed by the Sun’s heat. Nevertheless even Parker cannot remain too near the Sun for too long. Instead the probe has been placed in a highly elliptical orbit that takes it in as close as 24 million kilometers to the Sun before sending it back out to 100 million kilometers, a distance that will allow the that heat shield a chance to cool off.

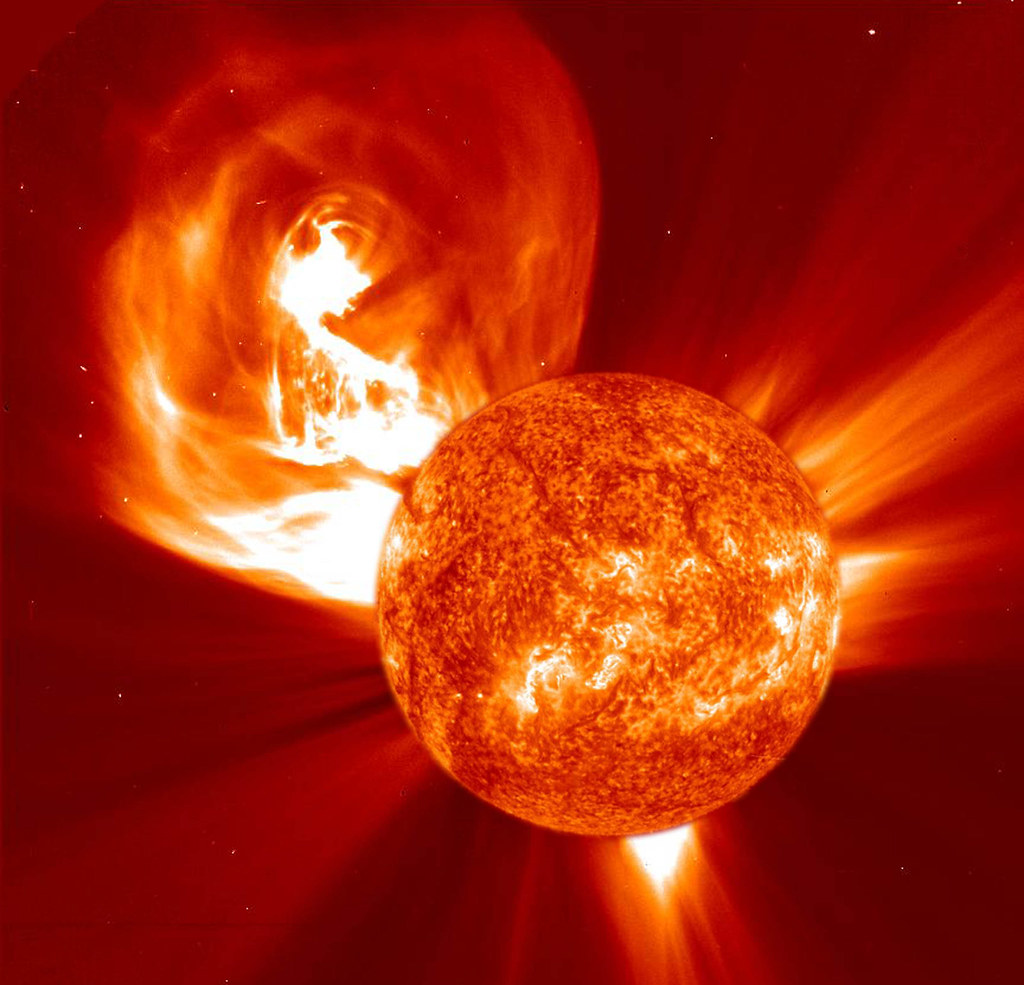

At its closest approach Parker actually flies within the Sun’s atmosphere, the corona, that glow around the Sun that can only be seen during a total eclipse. The question of why the corona is so hot, over a million degrees Kelvin, while the Sun’s surface is relatively cool, about 6,000 Kelvin, is one of the mysteries that Parker was built to study.

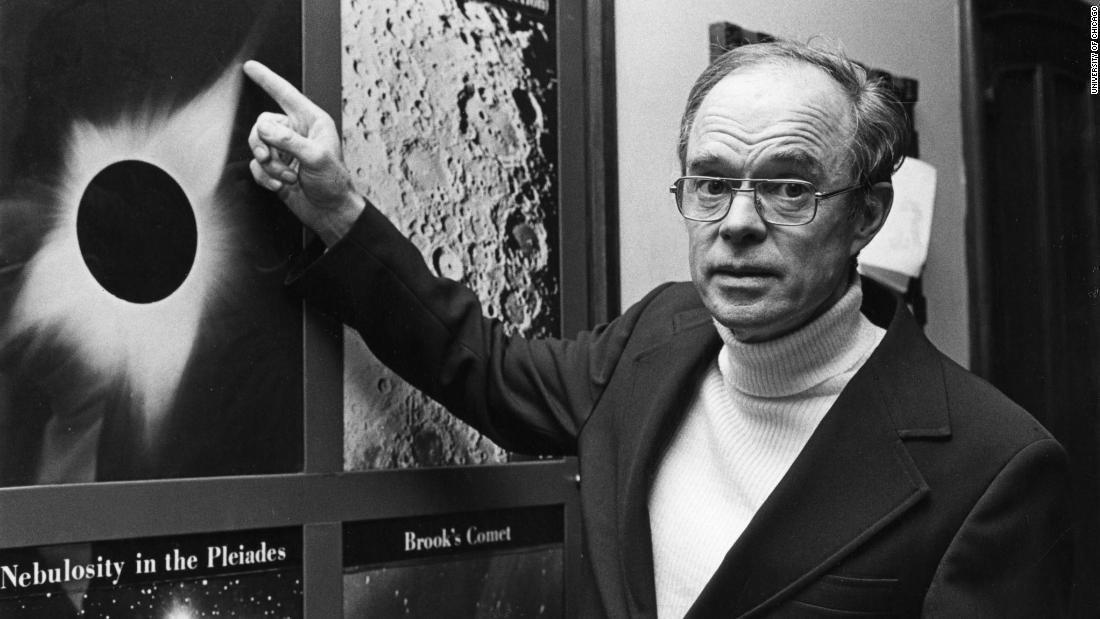

Learning more about the how the Sun generates the Solar wind, the steam of high-energy particles that among other thing causes auroras here on Earth, is another of the Parker Probe’s main missions. That particular mission is only appropriate since the spacecraft is named for Eugene Parker; the astrophysicist who back in the late 1950s first predicted the existence of the Solar wind. In fact Parker is the first NASA spacecraft to be named for a living scientist, a measure of the respect with which Eugene Parker is held in the space community.

So far the Parker Solar probe has completed three of its planned 24 close passes and now NASA has released the first data dump of measurements taken by the probe. In a series of papers presented at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union on December 11th NASA scientists revealed new discoveries about how the Sun generates the Solar wind along with how the magnetic fields within the corona switch polarities on a period ranging from a few seconds to a few minutes.

The papers also detail how the density of dust particles in the atmosphere actually goes down as you get closer to the Sun. This phenomenon is probably due to the pressure of the light and sub-atomic particles being ejected by the Sun and of which the Solar wind is formed. During its most recent close approach back in November Parker was actually able to observe the effect of a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) on the Solar wind revealing how a CME acts as a ‘snowplow’ pushing the wind ahead of it with increased energy.

And the Parker probe’s mission is only beginning; NASA is planning on another 21 close approaches to the Sun. In fact just next month Parker is scheduled to use a gravity assist from the planet Venus which will send it on an orbit that takes it even closer to the Sun. Eventually the space probe is expected to come within a mere 6.16 million kilometers of the Sun and to reach speeds of 690,000 kilometers per hour, a wild ride indeed.

The Parker Solar probe’s mission is scheduled to last through 2025, who knows what secrets it will learn in that time about the star that is the very center of our Solar system.