Many common backyard birds throughout the world are known for the beauty of their calls giving them the common title of songbirds. Each species has its own particular call which are so distinctive that many experienced ‘birders’, that how bird watchers prefer to be referred to, can often tell you what species of bird is singing off in the bushes without ever getting a glimpse of the singer. In some ways the song of a species is as distinguishing as the colours of its feathers.

It’s the male birds that do all the singing, using their calls to announce their territory or attract mates and birdcalls are known to change very little over time. Nevertheless the song each species of bird uses is not instinctive, every generation of males must learn the song and therefore over time change will occur, however slowly.

That’s why Ken Otter, Professor of Biology at the University of Northern British Columbia was so surprised when he moved to the city of Prince George in the 1990s. While getting acquainted with the local fauna Dr. Otter discovered that the white throated sparrow ( Zonotrichia albicollis) population west of the Rocky Mountains used a two-note ending to their song quite unlike the three-note triplet that ended the songs of white throated sparrows throughout the rest of Canada.

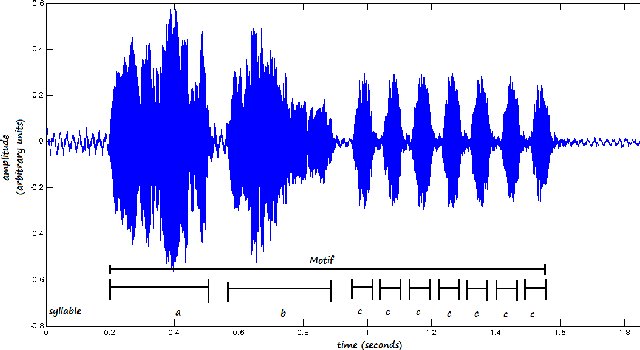

Intrigued Professor Otter discussed this new song style with several of his colleagues and together they decided to try to track the spread of the new two-note ending. In order to obtain as much field data as possible the naturalists contacted amateur bird clubs and organizations across Canada, enlisting the help of hundreds of volunteers. These field researchers used their cell phones to record the songs of white throated sparrows in their area and sent the recordings to Professor Otter who added them to his database.

With the huge number of recordings accumulated over 20 years by his volunteers Doctor Otter was able to observe the spread of the new song as bit by bit it moved eastward, reaching Alberta in 2004 and Ontario ten years later. So comprehensive is the data that Professor Otter was able to show that younger, juvenile males were learning the new song at the sparrows overwintering grounds and then taking the new song with them as they returned to their summer homes. So while Professor Otter and his colleagues may not be the first scientists to observe a change in the song of a species of songbird they have succeeded in developing the most extensive map of a cultural shift in a species of bird ever obtained.

Still one question remains, why did the new two-note ending so rapidly replace the old, traditional three-note ending? Doctor Otter can only speculate that female white throated sparrows might prefer the novelty of the new song. As the professor put it, “…we might find a situation in which the females actually like songs that aren’t typical in their environment. If that is the case, there’s a big advantage to any male who can sing a new song type.”

Cultural change being driven by males trying to attract females who are seeking some novelty in their lives, sounds quite human to me.

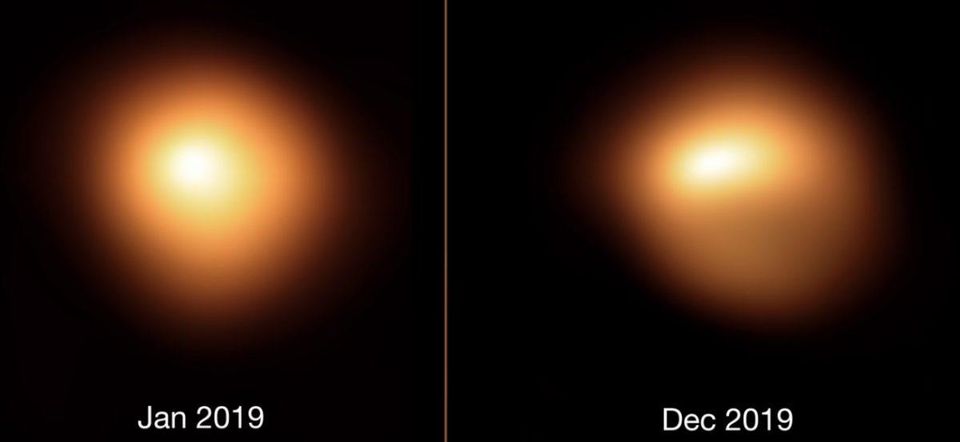

Before I go I’d like to take a minute to update a post I published back on the 4th of January 2020 about a significant dimming in the light coming from the star Betelgeuse, normally the 10th brightest star in our night sky. Betelgeuse is a giant red star that is nearing the end of its life and is expected to explode as a supernova in the near future. Near future for a star being sometime in the next 100,000 years.

While the energy output from Betelgeuse has been unstable ever since astronomers began making precise measurements of it more than a century ago the decrease that was observed late last year was unprecedented leading some astrophysicists to speculate that the star’s end might be near. However so far in 2020 the star seems to have stabilized itself leading astronomers to wonder what had caused the dimming.

Now a group of astronomers at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy have announced that they have discovered the direct cause of Betelgeuse’s drop in brightness. The team, led by Dr. Thavisha Dharmawardena have found that 70% of the star’s surface is now covered by Starspots presumed to be similar to the Sunspots on our own Sun. While Starspots have been detected on other stars before none have come anywhere close to being as extensive as those now seen on Betelgeuse. So now the question is, if the Starspots are the cause of Betelgeuse’s drop in brightness, what is causing the Starspots? And are those Starspots a prelude to an imminent explosion? Keeping in mind that imminent for a star could still mean sometime in the next thousand years.