The Atacama Desert of northern Chile is situated on a broad plateau between the Andes Mountains and the Chilean coastal range. Being at an average elevation of 3,000m and surrounded by two high mountain ranges little moisture reaches the Atacama so that it has been measured as being the driest place on Earth with the possible exception of some areas in Antarctica.

With an average annual rainfall of about 15mm you shouldn’t be surprised that there is little life in the Atacama, vegetable or animal. While those parts of the Atacama that receive some moisture are home to several species of cacti and saltgrass along with insects, scorpions and even a few lizards there are areas where the desert is so arid that no life can survive for very long.

However there is one form of life that recently has begun to rapidly multiply in the Atacama Desert, scientists, particularly the sub-species astronomers. In fact the very extreme nature of the climate in the Atacama is what has many scientists excited, even anxious to work there.

NASA scientists are interested in the Atacama because it is the region of Earth that most closely resembles the conditions on Mars, cold, dry and at 3,000m altitude even the air is thin. In fact a team from NASA duplicated the tests for life that had been performed on Mars by the two Viking landers and got the same results as the Vikings, no life. NASA has also used the Atacama on several occasions to test various instruments for several of their Mars landers.

But it’s the astronomers who really love the Atacama. The thin, dry almost cloud free air of the high desert along with the lack of city lights of any kind make it one of the best places on the surface of the Earth for viewing the Universe. Three large observatories have been built and are being operated by the European Southern Observatory (ESO). The United States by the way has built and maintained its largest observatories either on top of the Mauna Kea volcano in Hawaii or the mountains of the desert southwest.

Although the Atacama Desert has been used for astronomical observations for more than a century the first permanent observatory there was the ESO’s La Silla observatory that began operations in 1964. Currently La Silla operates 10 medium to small telescopes including the 3.6m New Technology Telescope that back in 1984 was one of the earliest telescopes to employ adaptive optics.

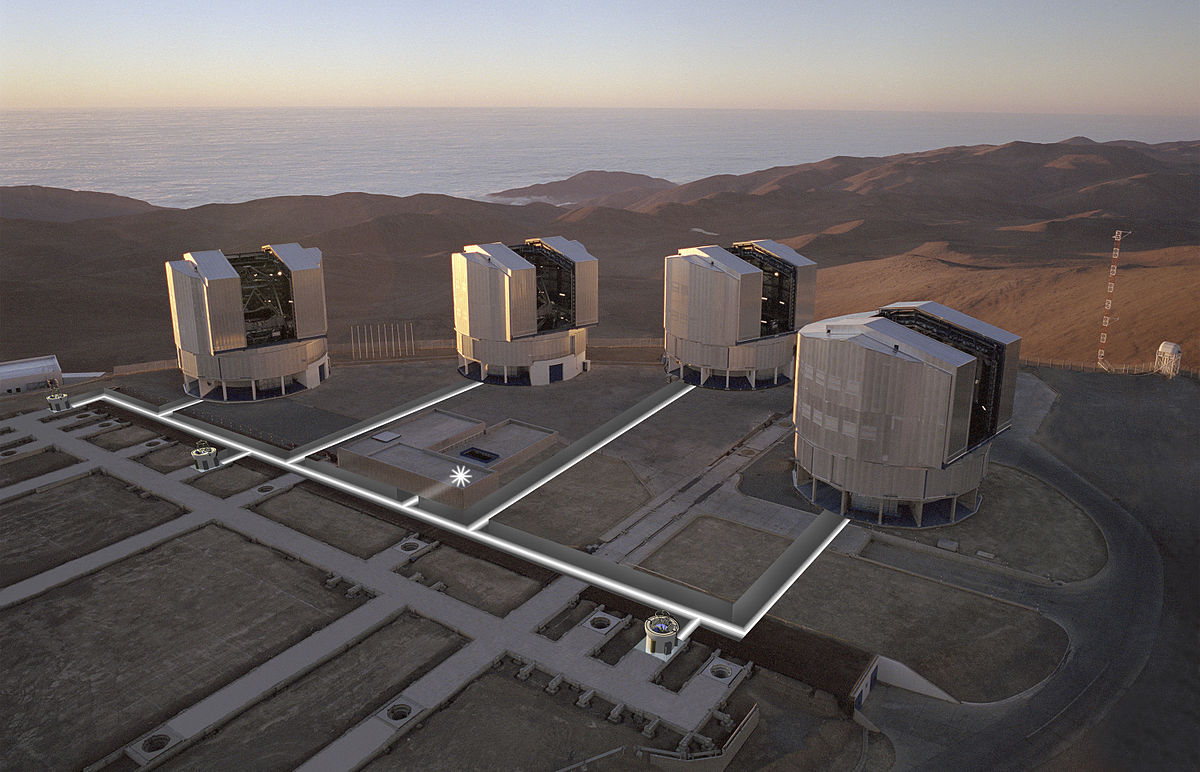

The largest optical telescope in the Atacama, indeed the second telescope in the world is the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at the Paranal Observatory. The VLT actually consists of four 8.2m telescopes whose light is ‘added together’ by means of computer controlled optics. This ‘adding together’ of the light from the four large telescopes effectively makes them into a single huge instrument. (Let me tell you a little secret. I understand the math used to perform this magical feat but I freely admit that the precision needed to do this accurately at optical frequencies makes my head swim!)

In addition to the four main telescopes the VLT also possesses four smaller 1.8m telescopes that are located at a distance from the larger ‘scopes. The light captured by the smaller instruments can also be added to that of the big telescopes allowing the VLT to conduct interferometric measurements of astronomical objects.

The third observatory in the Atacama Desert is the Llano de Chajnantor, a radio observatory specializing in studying the Universe in millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths. In fact because water vapour in the air effectively blocks such high frequency radio and infrared light the arid Atacama Desert is really the only place on Earth’s surface where such an observatory could be built. The main instrument at Llano de Chajnantor is the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, a collection of 54 12m-radio dishes whose signals are again added together to make them act as a single instrument. (Performing this operation at radio frequencies is much easier; in fact I have worked on such adaptive arrays many times in my career.) Also at Llano de Chajnantor is a single 12m-submillimeter dish one of the few instruments in the world working at such high frequencies.

So that’s a brief description of the observatories and instruments expanding our knowledge of the Universe currently operating in the high Chilean desert. Today there are actually so many astronomers working in the Atacama that they even have their own hotel there.

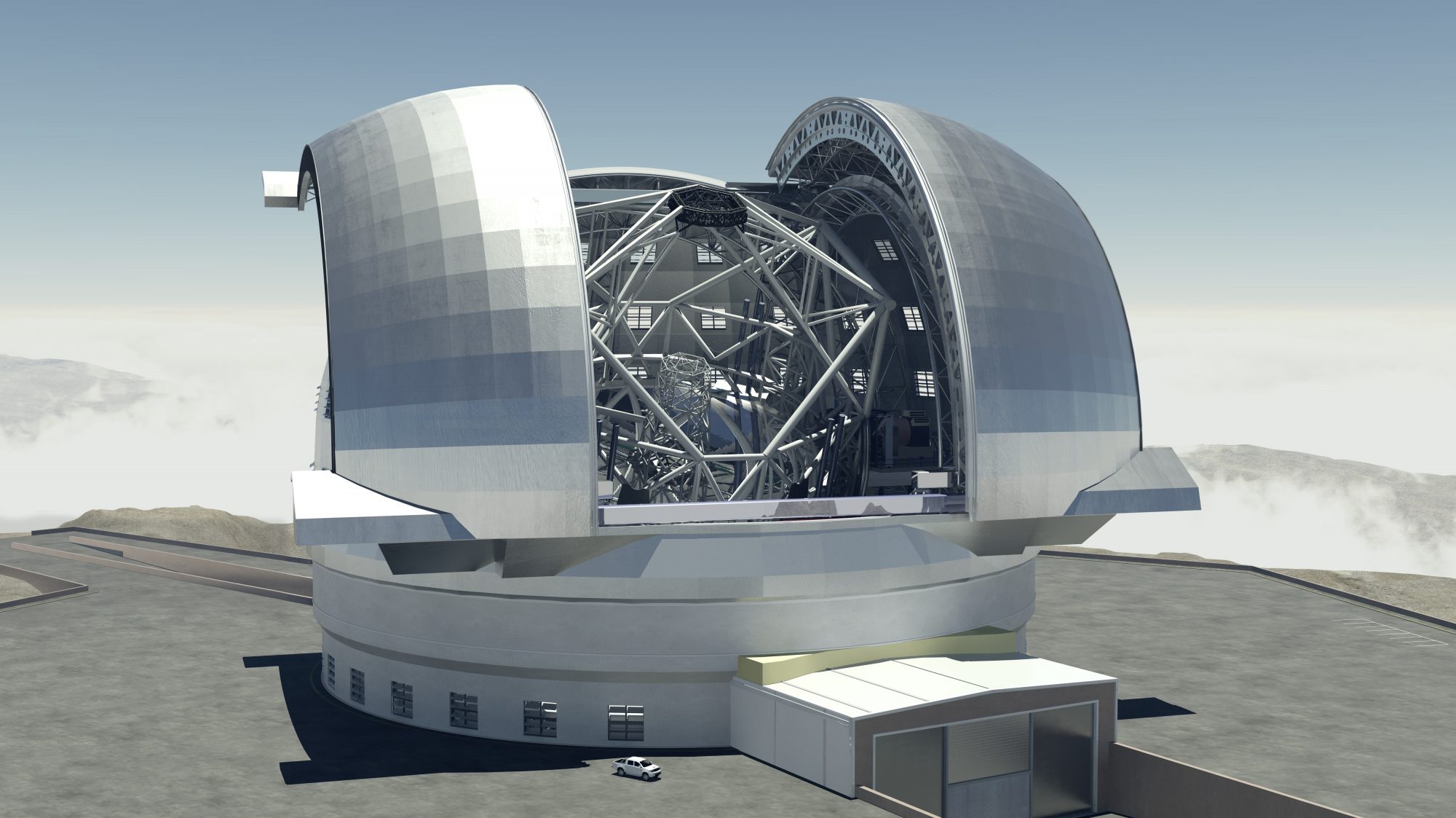

And there’s more to come. The ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) is now under construction at the new Cerro Armazones Observatory. When completed the ELT will have a primary objective 39.3 m in diameter making it the largest optical telescope in the world by a considerable margin. The telescope is expected to be completed and begin observations, a moment that astronomers like to refer to as ‘first light’, in 2025.

Right now we can only guess what kind of discoveries that instrument will make. All of this astronomical activity clearly shows that the future of the Atacama Desert as a haven for scientists is only beginning.