A lot to talk about today, a couple of topics that I’ve discussed in recent posts have come together in a single story so I think I start there.

The two subjects are bioluminescence; see my post of 8 August 2020, and fossils encased in Burmese amber, see posts of 16 December 2016, 1 June 2019 and 2 September 2020. Well in paleontology if you’re patient, and lucky, spectacular fossils will turn up from time to time including a 99 million year old, exquisitely preserved specimen of a lightning bug encased in amber.

Now insects in general don’t fossilize well, I have none in my collection, and fireflies, fire beetles and glowworms are especially rare since their bodies are softer than those of most beetles. So our knowledge of the evolution of bioluminescence in beetles is largely guesswork. Indeed, the current thinking is that bioluminescence first appeared in the larval stage of beetles as a defensive mechanism. Then, in order to retain the ability as adults the beetles also retained the soft body more typical of a larva.

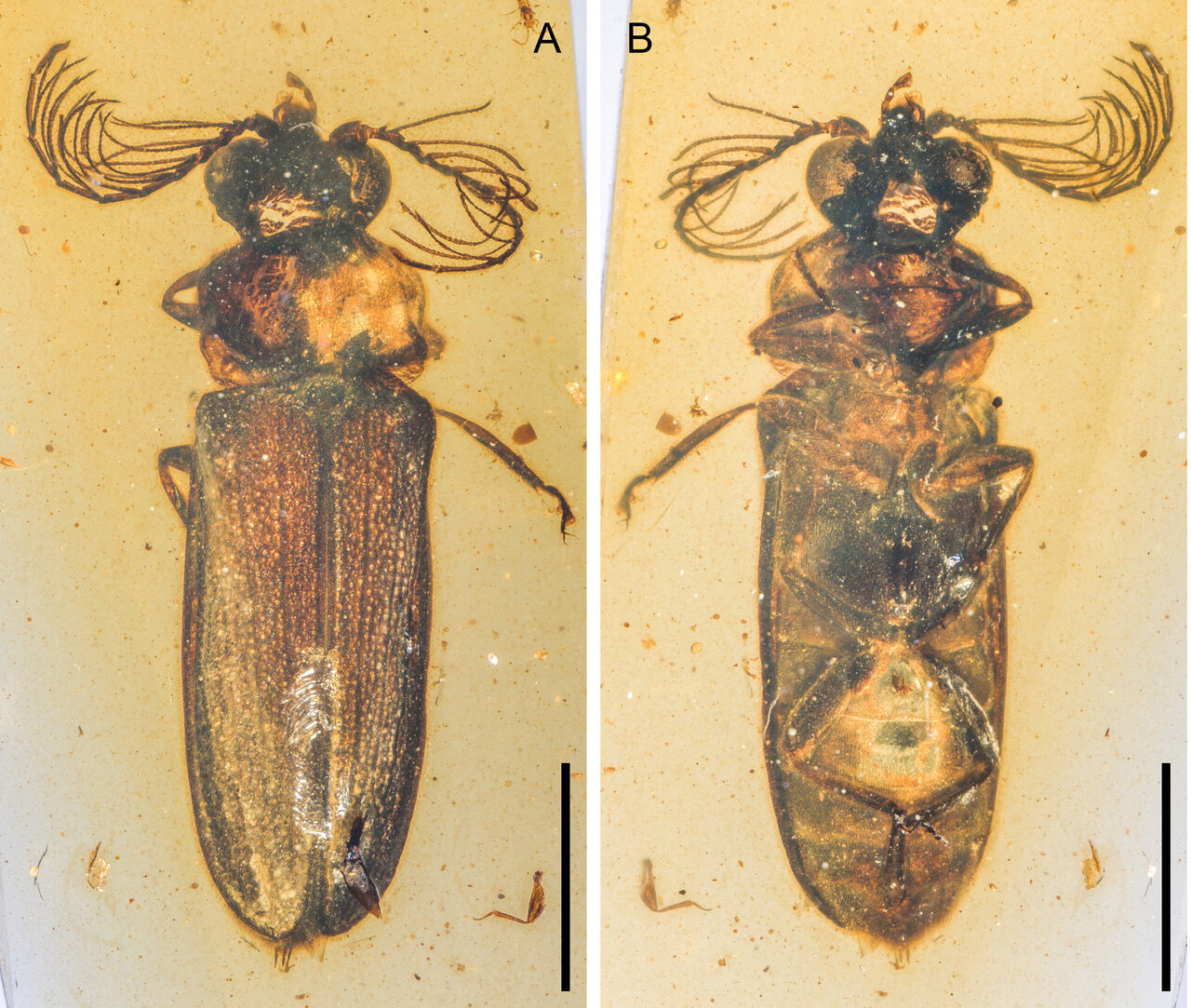

That’s one of the thing’s that makes the specimen from Myanmar, which has been given the name Cretophengodes azari, so valuable. Perfectly preserved in amber the specimen is both clearly an adult, clearly a male and just as clearly possesses the organs necessary for bioluminescence. While it is impossible to say for certain how the animal used its luminous organ the fact that it is a male raises the possibility that the light played a role in mating just as it does for modern species. One more example of how the fossil preservation of soft parts, this time in amber, is answering many of our questions about the past.

There are also some types of animals that have a very extensive fossil record but about whom we still have many questions because their hard shells fossilize so much easier than their soft bodies. In other words we know a lot about parts of the animal, and have a lot of questions about other parts.

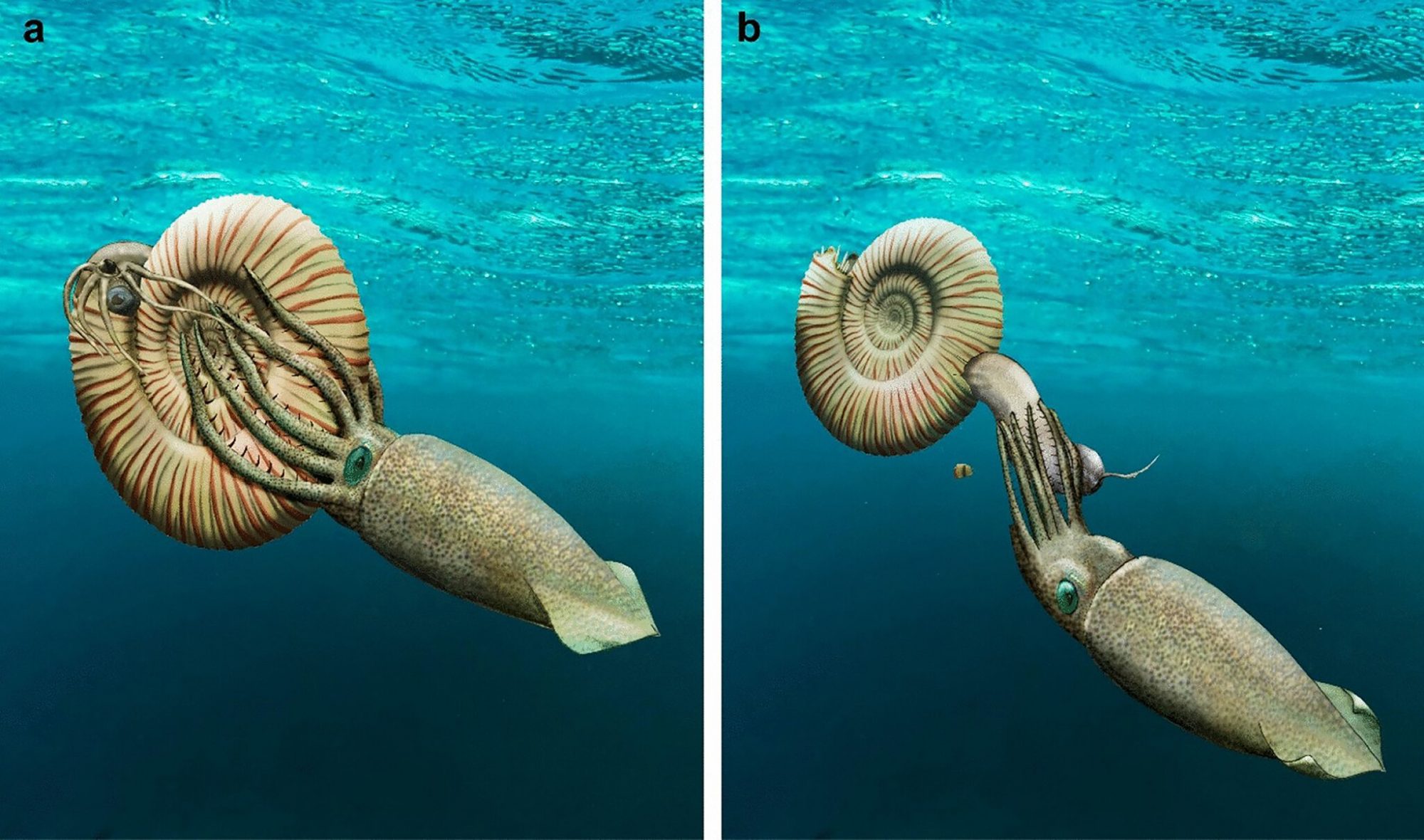

A good example of this are the Ammonites, extinct relatives of the modern nautilus. The coiled shells of Ammonites are very common, so common that they are commercially dug up and sold as knick-knacks. Hundreds of species of ammonites have been described based entirely on differences in the shells while paleontologists still argue over the details of the animal inside. Was it like a nautilus, or more like a squid, or maybe a cuttlefish, or something different from them all?

Such details may seem important only to professionals but remember we are talking about a large group of animals who survived for hundreds of millions of years. The nature of the ammonite animal is very important in the evolutionary history of life.

So when a fossil of a nearly complete ammonite animal, outside of its shell, is discovered that’s big news. The find comes from the Solnhofen limestone quarry in southern Germany, the same site that has produced those famous fossils of archaeopteryx. The limestone deposits of Solnhofen accumulated at the center of a lagoon some 150 million years ago. Like lagoon’s today the water was very salty, contained little oxygen and was very hot. Little could live there and any creature that died there would not decay but instead be slowly buried in the limestone. Because of this the fossils from Solnhofen retain clear evidence of the soft parts of the animals.

Other ammonites have been found at Solnhofen, but always in their shell so that their internal organs are hidden as in life. This specimen however is entirely naked allowing Professor Christian Klug of the University of Zurich and fossil collector Helmut Tischlinger to reconstruct the anatomy of the fossil. In order to discover every detail of the ammonite the researchers even took photographs of the fossil under Ultraviolet light.

Nearly the entire anatomy of the animal was there. The paleontologists could distinguish the digestive tract, with fecal matter still in the intestine along with reproductive organs and gills. The only parts that were missing were unfortunately the creature’s tentacles leaving still open the question of whether they resemble those of a nautilus or those of a squid.

So how did this ammonite come to die outside of it’s shell? We may never know. The likeliest event is that the animal died in its shell but then lost its grip and simply slid out. However Doctor Klug hypothesizes that perhaps a predator pulled the ammonite out of its shell. Then, while munching on the tentacles the attacker lost its grip and the mortally wounded ammonite sank to the bottom. However the ammonite met its fate its survival as a fossil will teach us a great deal about a large and important group of animals.

While ammonites were one of the most common denizens of the oceans back in the Mesozoic period on land one of the most common types of dinosaurs were the hadrosaurs, those two legged plant eaters often called duckbills because of their long, wide snout. Hadrosaurs were numerous both in terms of the total population of animals; plant eaters always outnumber predators, but also in the number of different species that are known to have existed.

For many hadrosaurs the key features that distinguish one species from a closely related one is skull shape and ornamentation. Hadrosaur skulls have been discovered that possess large frills, crowns and bumps. So varied and in some cases bazaar are the shapes of hadrosaur skulls that evolutionary biologists have even suggested that what we are seeing is a seventy million year old version of sexual selection, that hadrosaur skull ornamentation is like a peacock’s tail, having no practical use other than attracting females.

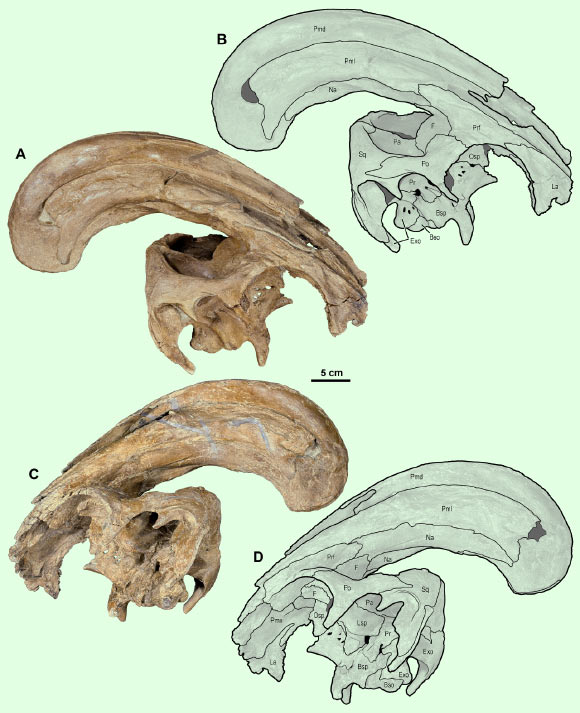

One such hadrosaur species is known as Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus, an animal whose nasal passages start near the animal’s upper lip, extends way up, a meter above their forehead, turns 180º around to come back to just above their eyes. The first skull of P cyrtocristatus was discovered in New Mexico in the year 1923 and dates back to some 75 million years ago.

That first skull sparked a debate about the purpose of P cyrtocristatus’s unusual nose. Ideas ranging from a snorkel to the long nose giving the animal a superb sense of smell have been advanced. The consensus opinion however is that the nose was used for both sexual display and to produce a loud, resonant low pitched roar that could have been heard for kilometers.

Now a new fossilized skull of P cyrtocristatus has been found in New Mexico not far from where the first skull was unearthed. Although most of the body, and even a portion of the skull had eroded away importantly the long nasal crest was preserved in greater detail than ever before seen. Indeed the new skull has already enabled paleontologists to better understand the relationship between P cyrtocristatus and its closest relatives P walkeri in Alberta Canada and P tubicen from younger rocks in New Mexico. The researchers also hope that the new find will enable them to learn more about how the crest developed as the animal grew.

The three fossils discussed here come from a very wide variety of animals but they all have one thing in common. By preserving a portion of the soft parts of the animal they have revealed some of the mysteries of life’s history here on Earth.