Back when I was in high school all living creatures were still being divided into just two kingdoms, animal and vegetable. Biologists were well aware of the problems that oversimplified scheme caused, fungi were obviously not plants and single celled organisms often had characteristics of both animal and vegetable, or sometimes neither. Some new classification system was needed but the biologists took their time creating one in order to make certain that they got it right.

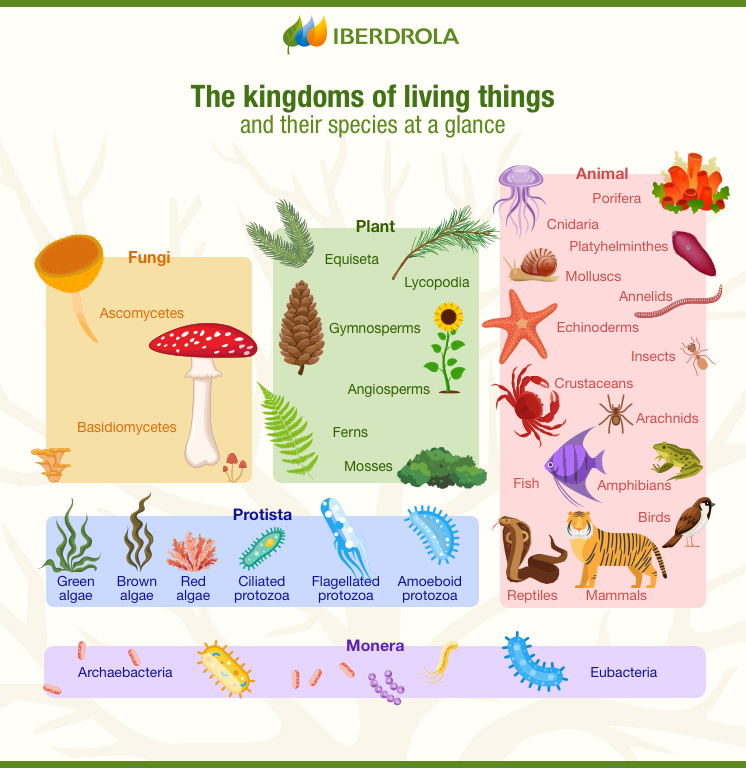

What they finally decided on was a five kingdom division that has in fact made understanding the relationships between the groups much easier. Multi-cellular creatures are now split into three kingdoms, animals, vegetables and fungi while single celled organisms with a cell nucleus, like an amoeba, are grouped into the protista and single celled organisms without a nucleus, the simplest life forms like bacteria are called the monera.

So one of the questions that this new classification scheme generates is, what was the first animal? What was the first multi-cellular creature that had to eat other creatures for their energy, as opposed to plants that generate their energy through photosynthesis?

Early evolutionary biologists were quite confident that sponges, members of the phylum Porifera were the earliest animals because they were certainly the simplest. In many ways sponges are nothing more than colonies of identical cells working in unison rather than the cells of most animals who differentiate and grow into separate organs. That means that sponges have no digestive system, circulatory system or nervous systems or even anything like muscles. Each cell moves its body in unison with the other cells near it generating a flow of water through the body of the sponge and then each cell captures and absorbs its own food particles from that water flow.

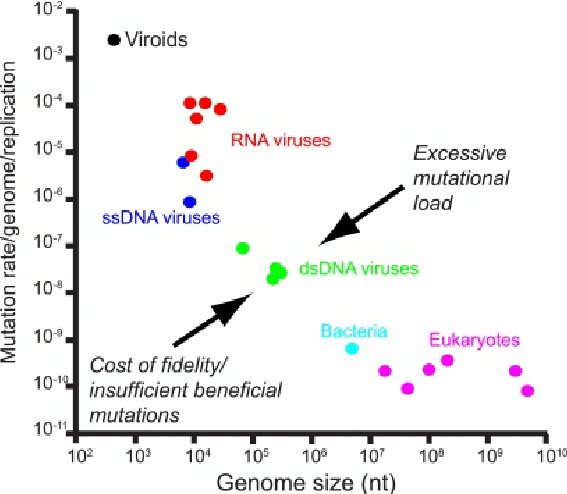

However, when biologists first used DNA analysis to estimate mutation rates in order to calculate which phylum came first it wasn’t sponges that looked like the oldest animals but rather another kind of creature known as ‘comb jellies’ or technically the Ctenophora. This discovery came as a considerable surprise because comb jellies are in many ways considerably more sophisticated creatures possessing not only a gut and muscles but even a very primitive nervous system.

The idea that comb jellies came first, then sort of devolved into the less complicated sponges before re-evolving for later more advanced creatures, like us, was hard for many biologists to accept. As geneticist Anthony Redmond of Trinity College in Dublin Ireland remarked however. “It may seem unlikely that such complex traits could evolve twice, independently but evolution doesn’t always follow a simple path.”

Still such surprising, even baffling results should be double if not triple checked. With that in mind Doctor Redmond and his colleagues reexamined the mutation rates for the two phyla with newer models that even take into account the rate of change for amino acids in the most common proteins. What they found was that the greater range of diversity of the comb jellies was caused by a burst of evolution early in their history leading to a false impression of greater age. The sponges, on the other hand have been a much more conservative group of animals whose lack of diversity made them look artificially younger.

These latest results clearly show that sponges are the earliest animals, just as biologists had always thought. They also show the danger in simply counting the number of changes, mutations in a DNA sequence and then using that as a measure of age. A group of animals that quickly diversifies in order to fill a large number of ecological niches can have a burst of evolution that imitates age. Just goes to show that while genetic studies can tell us a lot about the relationships between living things we still have a lot to learn about how to interpret the data they provide.

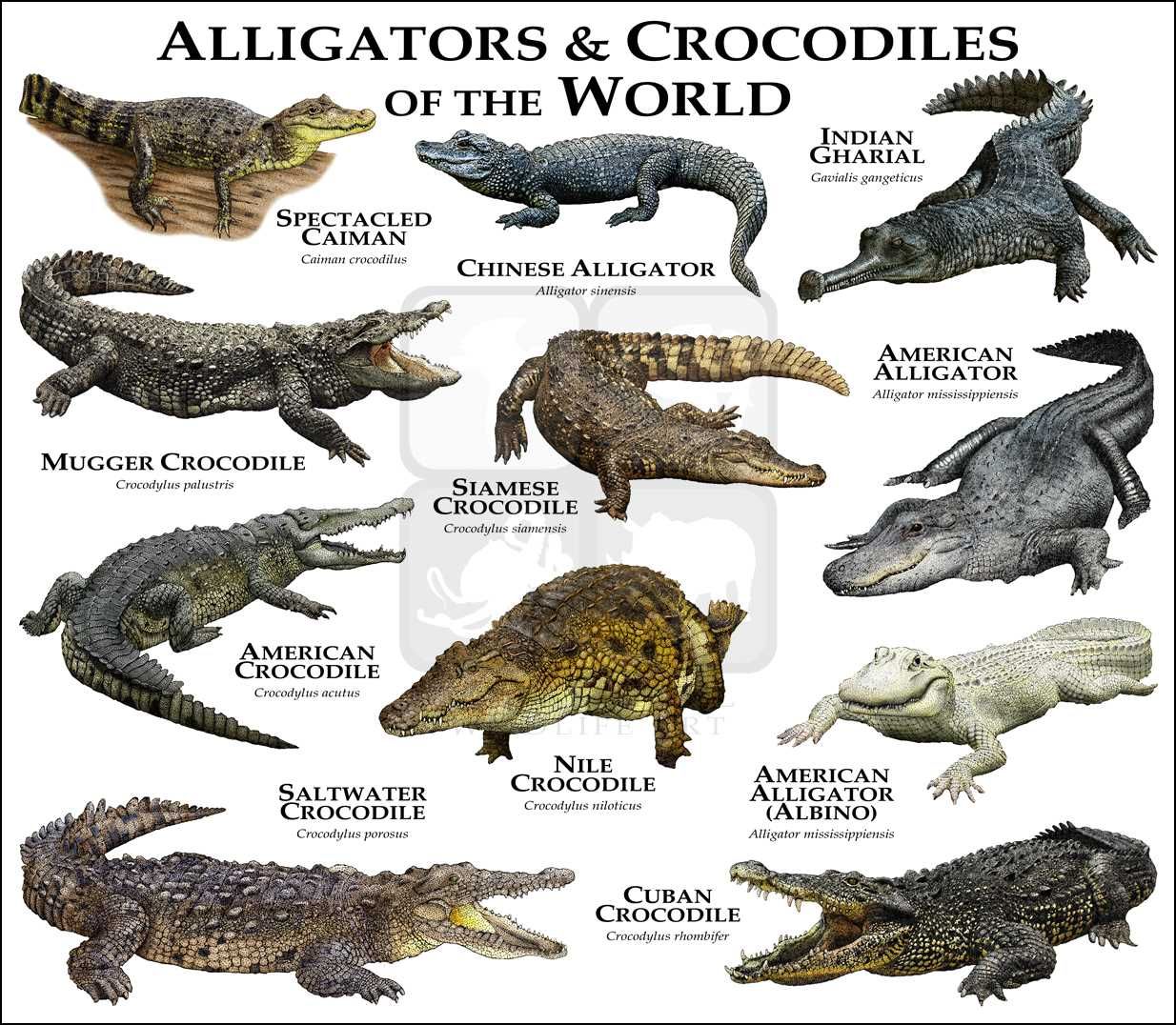

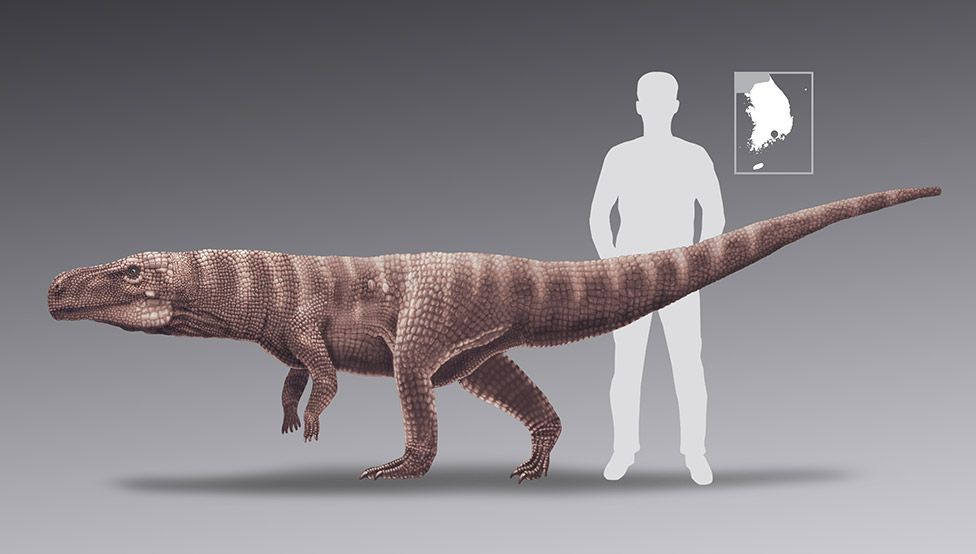

Another group of animals who are often considered to be very conservative like the sponges are the crocodilians. In some respects the 26 modern species of crocodiles, alligators and gharials all bear a considerable resemblance to each other and together seem to have little changed since the days of the dinosaurs. So much so that they are often, unfairly called living fossils.

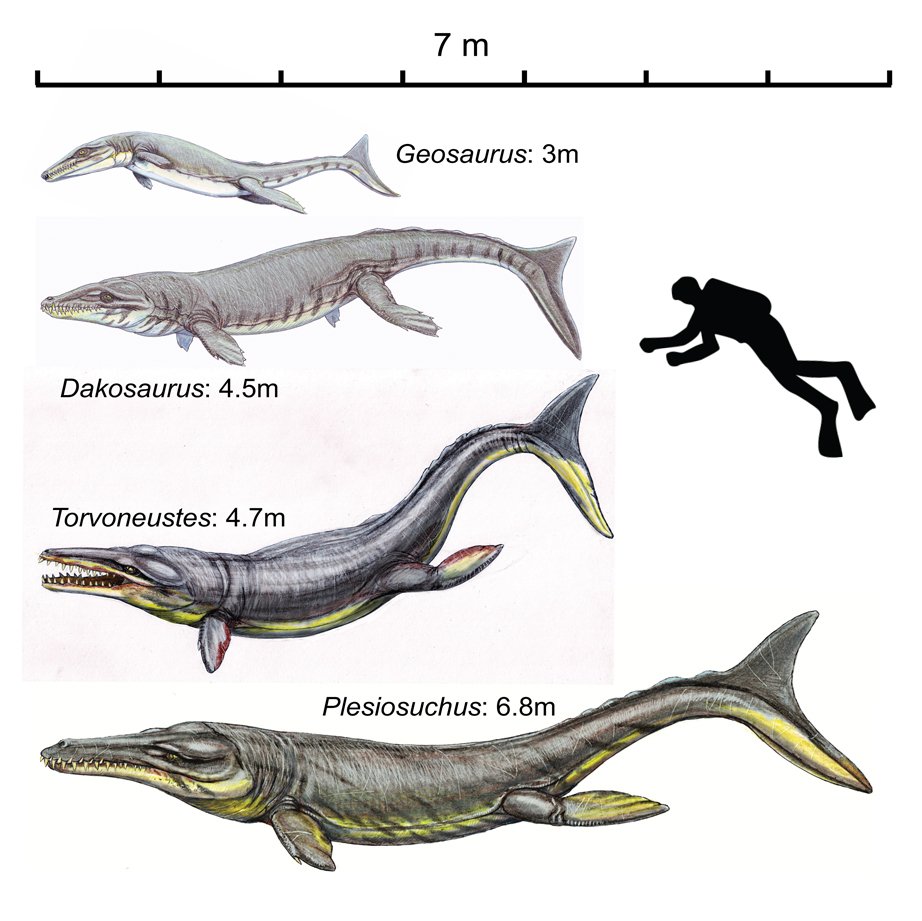

In fact however crocodiles were once a much more diverse and rapidly evolving group of animals, with swift running land dwellers, dolphin like swimmers and even herbivores, yes plant eating crocodiles! Modern crocodiles may be restricted to a narrow range of ecological niches but there was a time when crocodiles made up a large and very diverse group of animals.

A recent study by paleontologists at the University of Bristol in the UK illustrated the extent of crocodilian diversity. In a paper in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B the researchers, including lead author Doctor Tom Stubbs, detailed the findings gained from examining more than 200 skulls and jaws spanning the entire 230 million year long history of the group. Ancient crocodiles it turns out were another example of how spreading out into a number of different lifestyles led to rapid evolution and wide diversity. Proving once again that experimentation leads to success.

Unfortunately only a small portion of that ancient diversity managed to survive past the reign of the dinosaurs. So we are left today with only a narrow picture of what a crocodile can be. Of course the dinosaurs themselves were virtually wiped out 65 million years ago when an asteroid or comet struck the Earth leaving only their fossil remains to tell us their story.