As I have mentioned several times in these posts, 99% of the fossils that paleontologists, and amateurs like me find are the hard parts, the shells or bones of ancient animals. Soft tissue like muscles or internal organs are rarely preserved and even then they usually distorted in shape because of the enormous pressure they were under for millions of years. So it’s not surprising therefore that paleontologists got pretty excited recently by the discovery of a very well preserved 310 million year old brain.

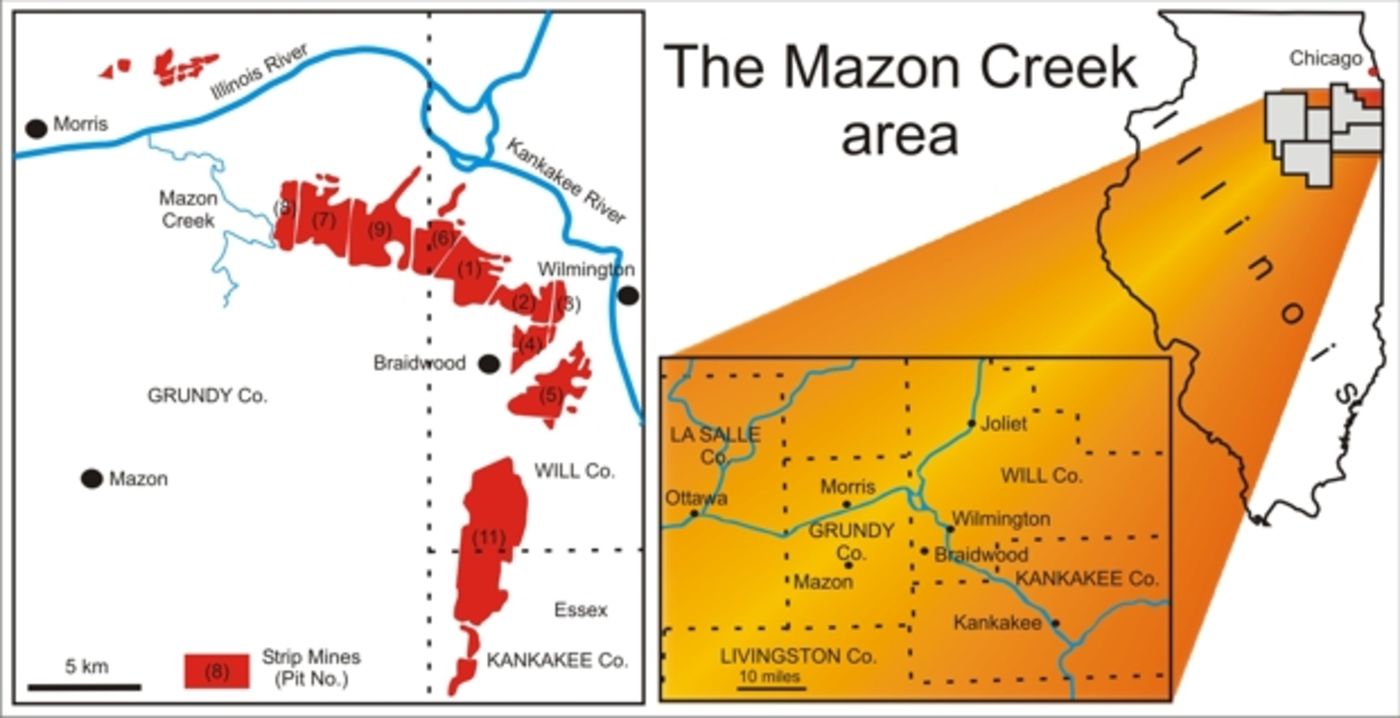

The brain in question belonged to a specimen of a species of horseshoe crab called Euproops danae and was found at the Mazon Creek fossil site in Illinois. The Mazon Creek site is famous for its excellent preservation of fossils from the Pennsylvania period some 310 million years ago. Many completely soft bodied species have been discovered in the iron concretions at Mazon Creek and are known only from that site.

The specimen of horseshoe crab was discovered and studied by a team of paleontologists from the University of New England in Australia, Harvard University in Massachusetts and Pomona College in California with the results published in the journal Geology. The identification of the preserved organ as the animal’s brain was made certain by comparing it to the brain of modern horseshoe crabs. So close is the resemblance that the fossil brain illustrates how little the horseshoe crabs have evolved in the last 300 million years, making them true ‘living fossils’.

So it seems that even some of the softest organs and even whole animals from the past can be preserved and studied, all that’s required to find one is patience and a lot of fossils to examine. But for those of us who associate fossils with big animals like dinosaurs it’s nice that big means big bones, bones that are more easily fossilized.

And the biggest of all the dinosaurs were the sauropods; those long necked and long tailed monsters like the Diplodocus and wrongly named Brontosaurus, whose scientifically accepted name is really Apatasaurus. Both Diplodocus and Apatasaurus were discovered more than a century ago in North America but sauropods have now been discovered on every continent. Recently new fossils from the early Cretaceous period, 120-130 million years ago in China are adding two new species of giants to that well-known group.

The fossils were discovered in the Turpan-Hami Basin in the province of Xinjiang China and were described in an article published in the journal Science Reports. One specimen detailed in the study consisted of seven vertebra from the neck of a new species of sauropod that has been christened Silutitan sinensis and is estimated to have been some 20m in length. The second specimen is made up of seven vertebra from the tail of a different individual and is also described as a new species, which they have named Hamititan xinjiangensis. The researchers estimate the length of H xinjiangensis as being more than 17m.

The third specimen consists of only a few vertebra and rib fragments that the paleontologists have been unable to identify for certain as either a known or new species but are confident that they do come from a sauropod. These new species of sauropod not only add to the ever growing number of known dinosaur species but help to round out our knowledge of the cretaceous period in the far east.

Another part of the world whose Mesozoic past is also being uncovered is Australia where a new species of pterosaur has been described in an article published in the journal Vertebrate Paleontology, and it’s also a monster. The fossil skull of the flying reptile, pterosaurs are not dinosaurs, was discovered by a longtime amateur fossil hunter Len Shaw and has been given the name Thapunngaka shawi, which means ‘Shaw’s Spear Mouth’ in the local indigenous language.

The skull measures a little over a meter in length and would have contained about 40 sharp spiky teeth. By comparing it to related species researchers estimate that T shawi would have had a wingspan of about seven meters. The researchers speculate that T shawi probably flew above the vast inland sea that covered much of Australia back in the early cretaceous catching fish in much the same way as a modern pelican does.

In order to be able to fly the bones of pterosaurs were mostly hollow and easily broken. This makes fossils finds of pterosaurs rare and valuable, in fact the skull of T shawi is only the 20th pterosaur fossil to be found in Australia over the last 50 years. Nevertheless T shawi, like the sauropod species from China, does help to complete our picture of the living creatures who inhabited these parts of the world more than 100 million years ago.