One of the most fundamental questions waiting to be answered by science is “How did Life on Earth Begin?” For most of human history this question was answered by a story from myth or legend rather than by science. Our local chief god created the universe and all living things in some way. The first chapter of Genesis is not only a typical example of this but even gave us the word that we use to describe the whole process, genesis.

Basically our ancestors thought that ‘who’, created life was more important than ‘how’ it was done. After all we poor humans could never understand the mystery of how life was created. That was god’s greatest secret and it was enough for us to know that he did it. It’s only been since the start of the scientific revolution and Darwin’s demonstration that all modern living creatures have evolved from earlier forms of life that scientists first began to wonder how the first living thing, the ancestor of all life on Earth ever became alive.

The search for a answer to that question is the thesis behind Michael Marshall’s new book ‘The Genesis Quest’. Starting at the very beginning Marshall discusses not only the mythology but also several reasoned although not scientific hypothesis such as the èlan vital and spontaneous generation. It’s once the actual chemists and biologists begin working on the problem however that ‘Genesis Quest’ really gets good.

Reviewing the early advances on just what life is and where living things come from Marshall has certainly done his homework. From Robert Hooke’s discovery of cells, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek’s descriptions of microscopic ‘animalcules’ and Friedrich Wőhler’s first synthesis of an organic chemical to Darwin himself we see how science was forced, almost against itself to consider the question of how the first living thing came into existence.

By the way I just illustrated one of the key elements of ‘Genesis Quest’, you will be reading about a lot of discoveries made by a lot of different scientists. Some of the scientists will be famous, like Louie Pasteur but there will also be some not so famous ones like botanist Matthias Schleiden who was the first to definitely assert that all living things were made of cells. In Marshall’s telling each of these discoveries becomes a tale in itself and the whole becomes woven together for a grand story, the ‘Genesis Quest’.

In fact the cast of characters in ‘Genesis Quest’ is so large that it’s difficult to keep track of everyone without a scorecard. For example the physicist George Gamow, best know as an early proponent of the Big Bang theory is given a brief mention because he was the first to suggest that a group of three DNA bases could provide the code for the 20 amino acids used in the proteins of living cells. Gamow’s steady-state rival, astronomer Fred Hoyle is also mentioned because late in life he became an adherent of life on Earth originally coming from outer space, a theory known as Panspermia. (I mention Gamow and Hoyle because I just ordered a new book “Flashes of Creation” about the beginnings of the Big Bang theory in which Gamow and Hoyle are the two main characters. I can’t wait to read it!)

Much progress was made during the 20th century as Alexander Oparin and J. B. S. Haldane first developed the ‘primordial soup’ model of the beginning of life. This model saw its greatest success with the Miller-Urey experiment in 1953, which even today is still touted as evidence that simple chemical reactions on the early Earth could produce complex organic compounds.

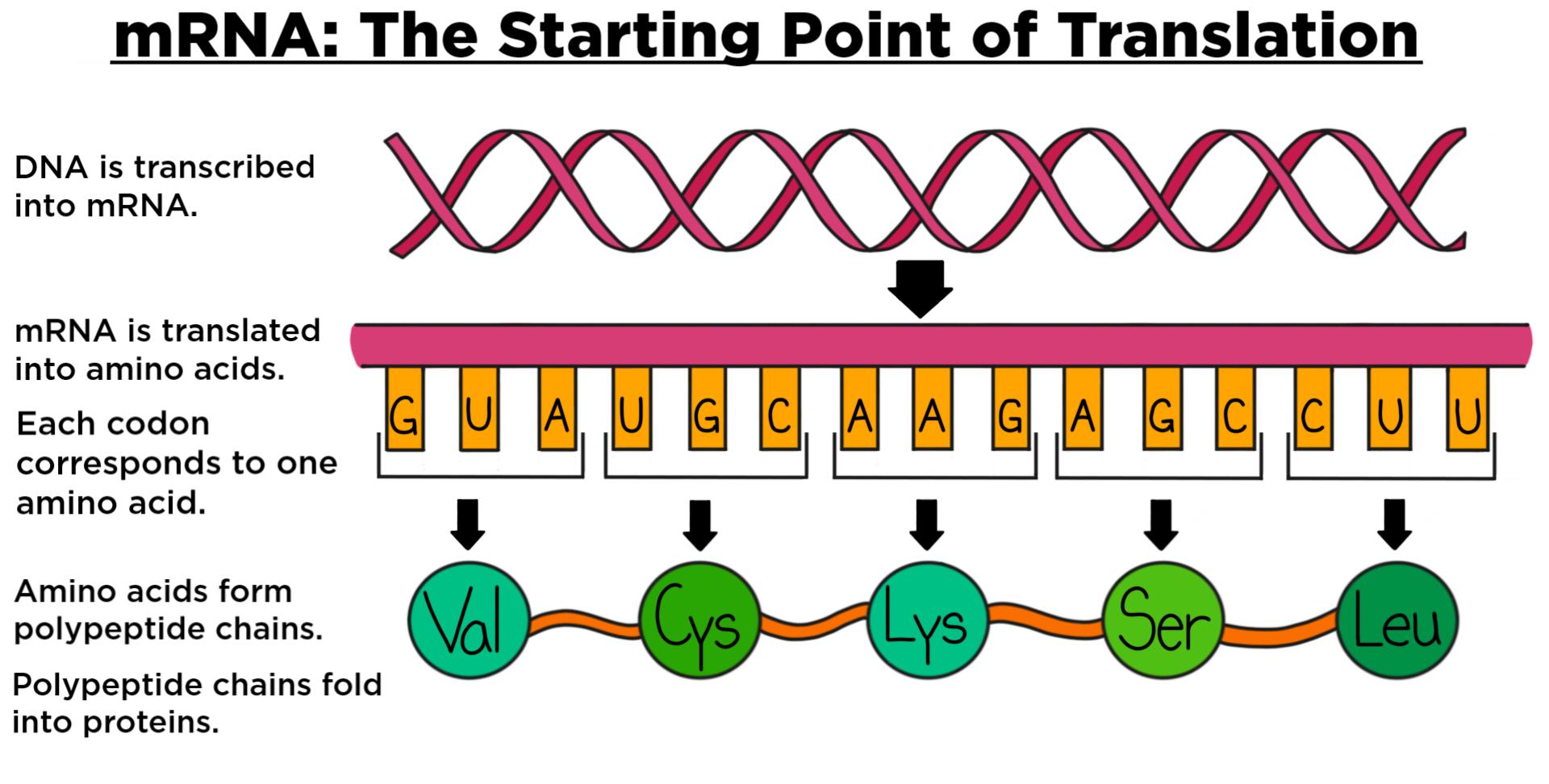

But 1953 was also the year that Watson and Crick first described the shape of the DNA molecule and in the years thereafter the very intricate and complex mechanism by which DNA builds proteins, DNA to Messenger RNA to Transfer RNA to Ribosome to Protein was discovered bit by bit. Such a complex chain of very delicate chemical reactions could never have arisen spontaneously in a primordial soup. So a new model of RNA first for the beginnings of life arose to challenge the protein based primordial soup model.

However both proteins and nuclides don’t last long in nature, so another model; a cell wall first model was also developed. From the 1970s throughout the 1990s these three models fought fiercely over who was right with none of them able to gain the upper hand.

Finally, in the last chapters Marshall discusses the modern synthesis that has developed since about 2000. A self-replicating molecule contained inside a lipid shell, something that has already been achieved by the chemist Jack Szostak. Marshall also asks the question, just how complex do ‘protocells’ like Szostak’s have to be in order to be considered ‘alive’. Have we in fact already created life in the labouratory?

Throughout ‘Genesis Quest’ Marshall manages to keep his descriptions of the, sometimes very sophisticated experiments and theories both simple and understandable. At the same time however he also includes footnotes with more technical information as well as sources for further reading. A well regarded science writer whose has worked for both New Scientist and the BBC Marshall knows just how much detail is needed in order to tell the story he wants to tell. ‘Genesis Quest’ is in fact a fast paced, very enjoyable overview of one of the most important scientific endeavors of all time. I cannot recommend it enough to anyone who is interested in how science and scientists work.