The ‘Age of the Dinosaurs’ is technically known as the Mesozoic or middle period of multi-cellular life here on Earth. So much of the research into this era of Earth’s history deals with dinosaurs that it’s almost surprising to come across stories about other kinds of life forms from the Mesozoic. Here are a couple.

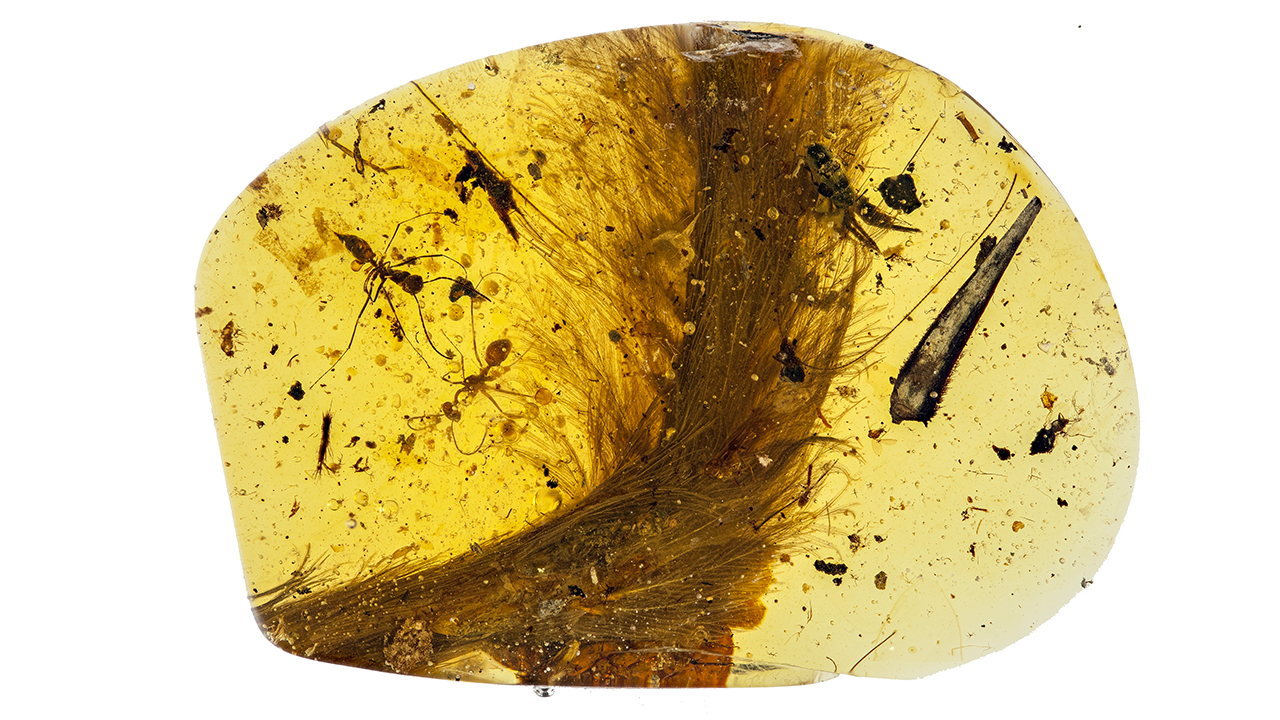

The first discovery concerns the fossils preserved in four chunks of 99 million year old amber recently unearthed in the country of Myanmar. Now, I have already discussed some of the extraordinary finds preserved in the amber that has been mined in that troubled country, see my posts of 16 December 2016 and 1 June 2019. Even before the military coup that swept away the democratically elected government in February of 2021 scientists had been wary of obtaining fossilized amber from Myanmar for fear that the money could help to support the military, or criminal smugglers or both.

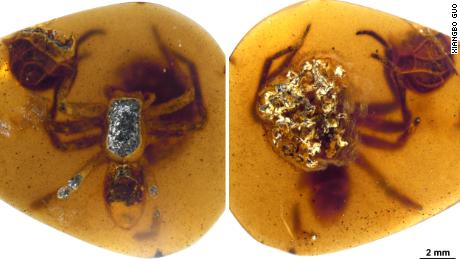

All of the political nonsense surrounding Burmese amber is keeping scientists from being able to properly study one of the most important fossil sites known while at the same time allowing valuable specimens to fall into the hands of unscrupulous dealers. Fortunately the four specimens in the latest study were obtained back in 2017 and the results of their study are only now being published. What the pieces of amber have revealed are spiders, in fact an entire family of spiders.

You didn’t know that spiders lived as families, well there are actually many species of spider where the mother provides a considerable amount of maternal care to her offspring while they’re young and that is exactly what the specimens preserved in amber illustrate. Based upon the mother spider’s facial appendages, spineless legs and ‘sensing hairs’ or trichobothria she belonged to a now extinct family of spiders called Lagonomegopidae.

The female was positioned directly above her egg sack, the spiderlings clearly visible inside. Her stance strongly suggests that she is protecting her offspring in a way identical to female spiders today. That such behavior has a long history has been suspected but according to study co-author Paul Selden of the University of Kansas Department of Geology, “it’s lovely to have actual physical evidence through these little snapshots in the fossil record.”

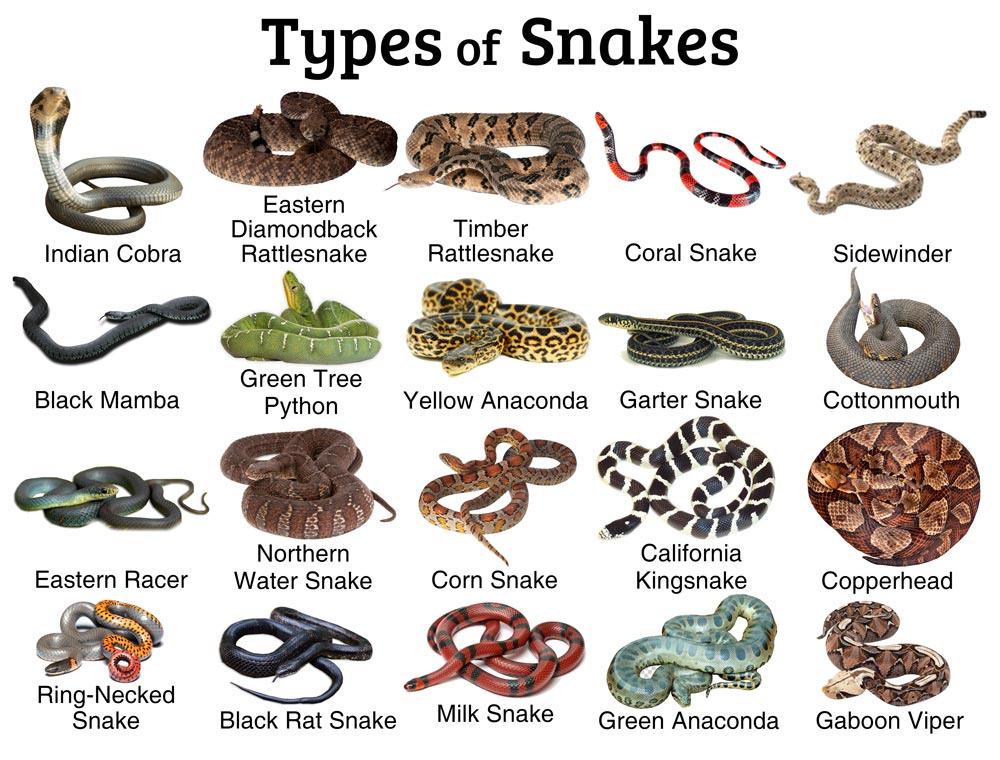

Spiders are of course one of the groups of animals that managed to survive the extinction event that killed all of the dinosaurs. And now a new study is revealing how another well-known group, the snakes, barely endured that cataclysm.

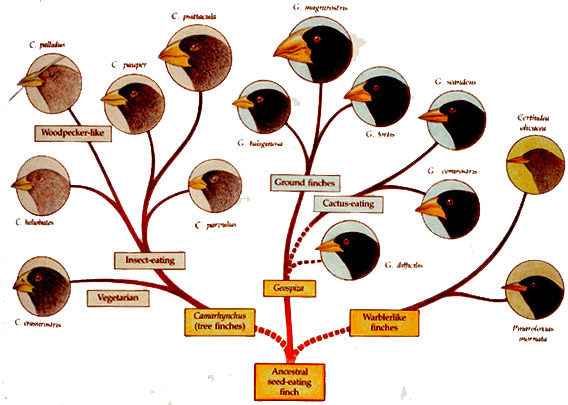

Today there are more than 4000 species of snake living in all but the very coldest of climates. The new study, published in the journal Nature Communications by scientists at the University of Bath in collaboration with researchers from Bristol, Cambridge and Germany have used fossil specimens and DNA samples from living species to outline the evolutionary history of all snakes. What they found was that, after the asteroid strike that killed the dinosaurs there were only a very few species of snake remaining in the world, and possibly only in the southern hemisphere.

In the several million years after the asteroid snakes not only spread throughout the planet but also diversified into the many types that we see today. The ability of snakes to live underground and go long periods of time without eating were no doubt crucial factors in their survival but their rapid diversification also demonstrates how quickly species can evolve and change after major disasters when a large number of ecological niches open up.

As described by lead author Dr. Catherine Klein, “It’s remarkable because not only are they surviving an extinction that wipes out so many other animals but within a few million years they are innovating, using their habitats in new ways.” By wiping out so many species the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs actually played a creative role in the evolution of many new species, including us of course.

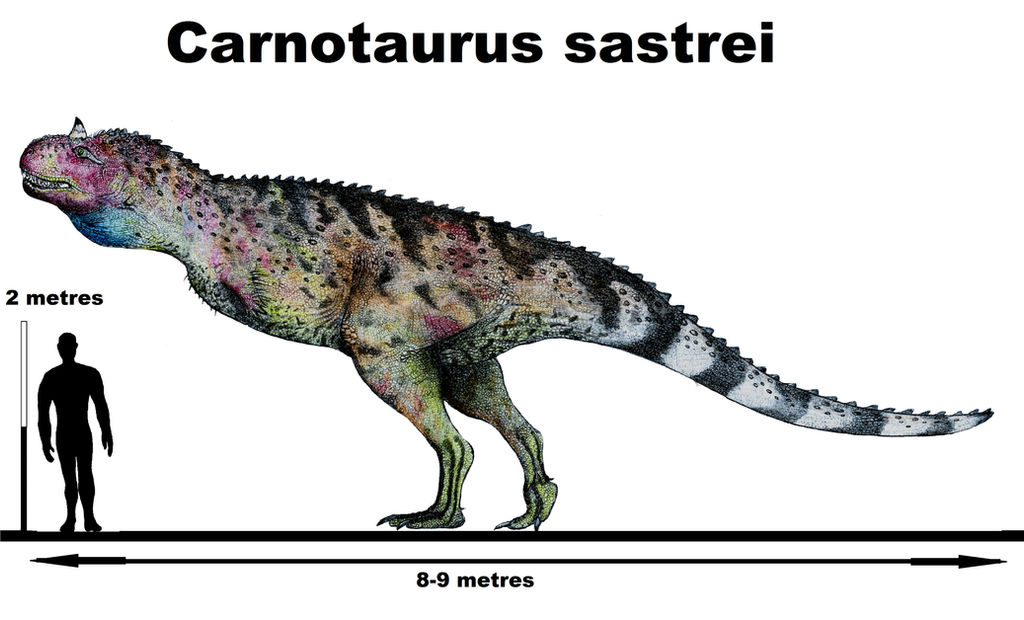

But I can’t write a post about animals from the Mesozoic without at least mentioning one species of dinosaur. The species I’ll talk about is little known, in fact only one fossil specimen has ever been discovered but that single fossil was so well preserved that paleontologists have even been able to learn a great deal about the animal’s skin.

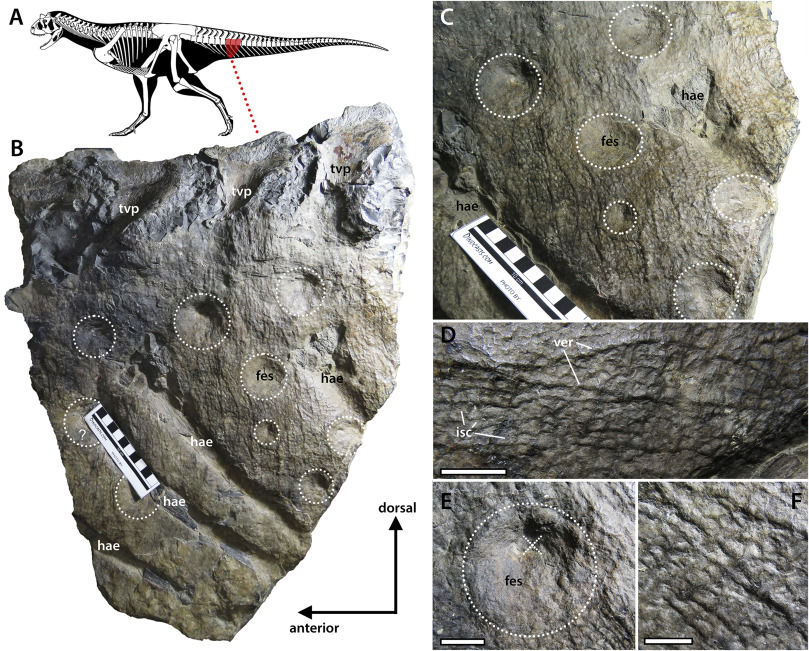

The dino is question is called Carnotaurus sastrei and is an 8 meter long carnivorous theropod dinosaur related to the famous Tyrannosaurus rex. Unearthed in 1984 in Patagonia the fact that the fossil included exquisite impressions of the animals skin caused quite a stir at the time. A full-scale examination of those impressions was never carried out however and it’s only now that the details are being revealed.

The new study details how the animal’s skin was a complex tapestry containing not only reptilian scales but also bumps, wrinkles and even thorns. Indeed for a reptile the number of scales was quite small and for the most part the skin reminded the researchers more of the hide of an elephant than a modern lizard or crocodile. The big news however is that from head to tail there was not a sign of anything resembling a feather on Carnotaurus.

In the last few decades of course there has been growing amount of evidence that our modern birds are closely related to the theropod dinosaurs. Indeed some fossils have shown that a few of the smaller species of dinosaurs may have had at least portions of their body covered with feathers in order to keep them warm. Some paleontologists have even gone so far as to suggest that T rex himself may have had a light covering of feathers on its head and legs.

Well, if the evidence of C sastrei is any indication then we can spare T rex the humiliation of suggesting it was covered by pretty feathers. That makes sense to, larger animals have an easier job of regulating their body temperature, it just takes them longer to either cool down or warm up. That’s why elephants have so little hair.

So there you have it. Three stories from the Mesozoic that illustrate something of the ways that living things evolve.