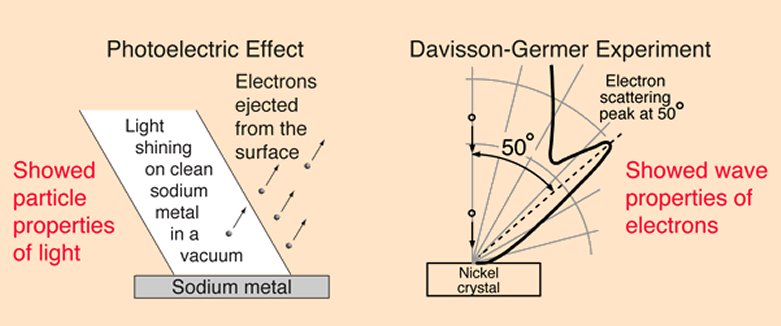

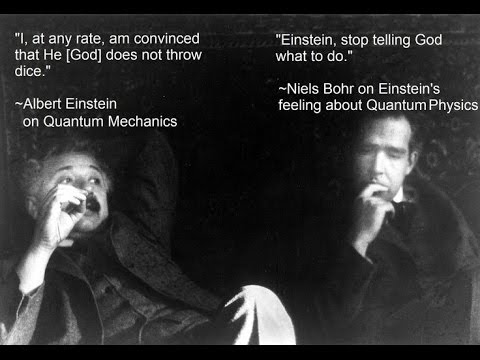

The history of science may not be bloody, but that doesn’t mean that it hasn’t had some memorable fights. Often the conflict is between a new idea and an entrenched opinion, such as the flight between Darwin and the creationists over evolution. Other times two opposing ideas can battle for decades or more before forming a synthesis. For example Newton thought that light was made of particles but Hyugens demonstrated that they were made of waves, only to have Einstein come along 200 years later and show that they were both, which you saw depended on their energy and what experiment you were performing.

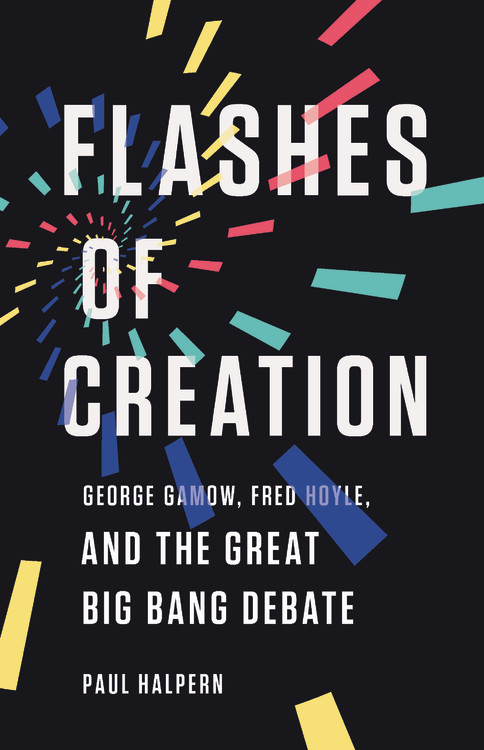

The book ‘Flashes of Creation: George Gamow, Fred Hoyle and the Great Big Bang Debate’ by Paul Halpern is about another such battle that took place from the 1930s through the 1960s over the very nature of the Universe in which we live. In fact a religious debate over this issue had been going on for millennia. Was the Universe eternal as the Hindus and Buddhists maintained or was there a moment of creation as the religions of the book, Judaism, Christianity and Islam proclaim.

By the 20th century it was science’s turn to take up the issue but of course the ideas of science have to account for the observed facts about the Universe as discovered by astronomers. By 1935 the most important of these facts had been established by the work of astronomer Karl Hubble. Using the 100-inch Hale telescope on Mount Wilson outside of Los Angeles California Hubble had described a Universe that was unimaginably large and filled with millions of galaxies. One more thing, Hubble showed that the Universe was expanding, those galaxies were moving away from each other.

That expansion of the Universe fit in well with Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity. Indeed the great physicist had been having problems trying to use his equations to describe a static Universe, an expanding one worked much better. But if you run an expanding Universe backward in time you get a contracting one, you get a Universe where all of the galaxies are getting closer and closer until if you go far enough back in time all of the matter that exists is squeezed together into a big ‘Cosmic Egg’.

It was the Belgian physicist Georges Lemaître who first proposed this idea that the Universe had a dense, hot beginning that expanded into what we see today, an idea that would later be called ‘The Big Bang’. There was a problem with Lemaître’s model however for if you inserted Hubble’s values for the size of the Universe and the speed that it is expanding you obtained an age for the Universe of about three billion years. But radioactive dating of Earth’s rocks gave an age for our planet of more than four billion years. How could the Earth be more than a billion years older than the entire Universe?

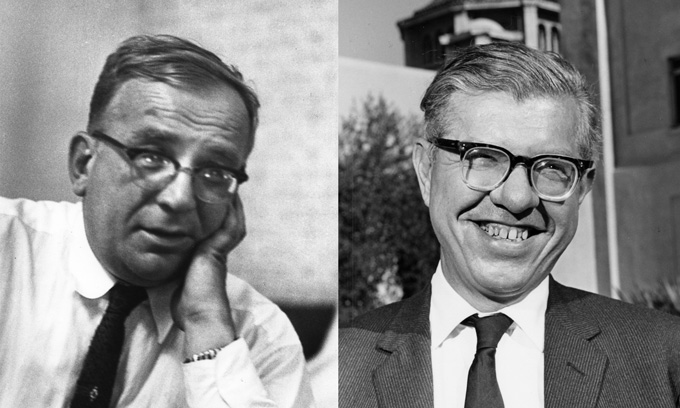

It’s at this point in the story that the two main actors in ‘Flashes of Creation’ take center stage. Russian physicist George Gamow would become the champion of the evolving Universe scheme of Lemaître while Fred Hoyle would become its greatest critic, co-developing an alternative Steady State / Continuous Creation theory. In the Continuous Creation theory as the Universe expanded new matter would be created to fill in the gaps and keep the Universe looking the same eternally. It was Hoyle who also first jokingly gave Lemaître’s model the name by which it is now famous ‘The Big Bang’.

Halpern’s book is as much biography as science, beginning with the early life of these two scientists and relating details of their other scientific interests and achievements aside from the nature of the Universe. Halpern also gives a detailed and uncompromising personal portrait of two the men. Both were independent minded and often came into conflict with the institutions were they taught. Gamow was widely known as a joker and socializer, i.e. drinker who late in life acquired a reputation as a drunkard. Hoyle’s brand of humour was more sophisticated, but could often cross the line into meanness.

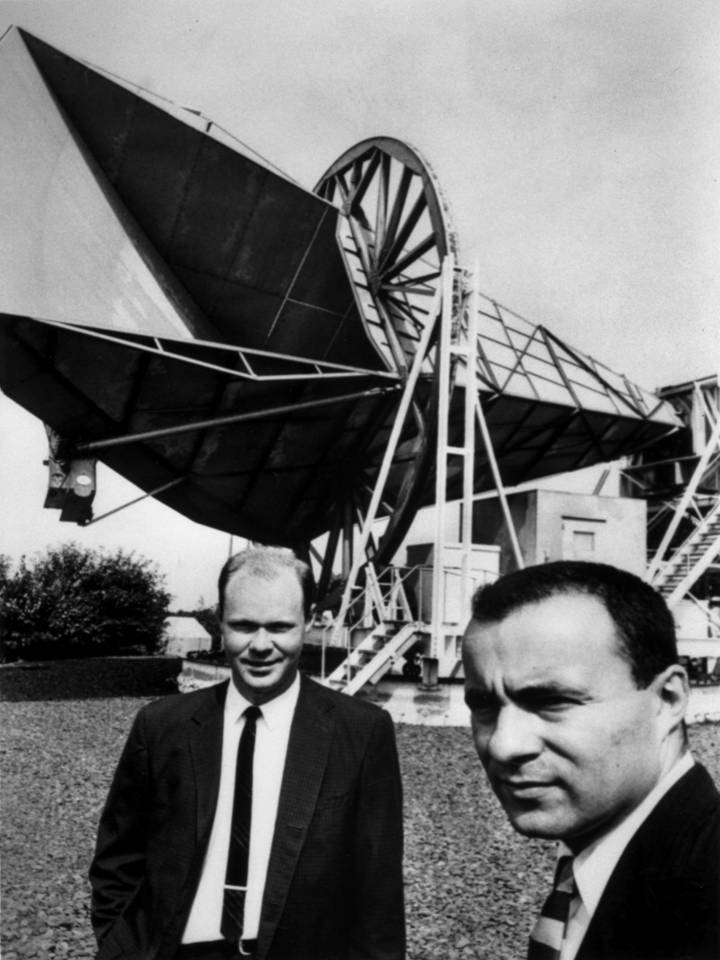

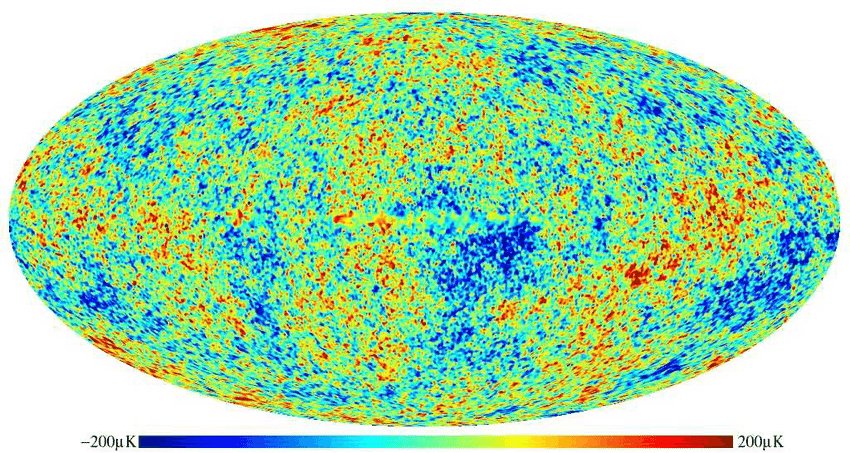

The crucial point in the story of Big Bang versus Continuous Creation happened in 1965 when radio astronomers Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson accidentally discovered the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) the leftover heat that erupted as the Big Bang. Gamow, along with his colleagues in Big Bang research Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman had predicted this leftover radiation but the Continuous Creation theory had no mechanism to account for it. The CMB is still considered to be the best, most conclusive evidence for the Big Bang.

The endings for both Gamow and Hoyle were rather sad. Gamow died just a few years after Penzias and Wilson had proved him right but at the same time stolen his thunder as the champion of the Big Bang. Hoyle, who never accepted defeat vainly tried to fit the CMB into a quasi-Continuous Creation but as his ideas grew more outlandish his reputation suffered.

‘Flashes of Creation’ tells this very important story in the fullest detail. Halpern has not only interviewed many of the surviving characters in the story, most especially the children of Gamow and Hoyle, but also uncovered letters and notes related to the conflict of ideas. By the way, Gamow and Hoyle only met once, and talked amicably. In fact there were never any ill feelings between these two giants of 20th century science; they just had different ideas. To bad all of our conflicts can’t be carried out in such a civilized fashion.

I must admit at this point that ‘Flashes of Creation’ does have a few flaws. Several times in the book Halpern praises Gamow for the illustrations that he made for his own popular books about physics, but ‘Flashes of Creation’ has none. As a firm supporter of the adage ‘A picture is worth a thousand words’ I can only say that many of the difficult concepts Halpern describes would have been helped with a few illustrations. Also, the book could have benefited from a little more proofreading. Really there are quite a few typos spread throughout the text.

Nevertheless I certainly recommend ‘Flashes of Creation: George Gamow, Fred Hoyle and the Great Big Bang Debate’ by Paul Halpern. This is one of the most important stories in the history of science and Halpern has penned the definitive book on the subject.