Even while the Covid-19 pandemic continues to rage around the world scientists have been reexamining the pandemics of the past in their efforts to uncover something useful for their fight against Covid. In these posts I have already mentioned the ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic of 1919-1920 and its similarity to Covid-19.

Now a team of researchers at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History has published a new study in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution of arguably the best known plague of all time, the ‘Black Death’ of the mid 14th century. Caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis the bubonic plague is considered to have been responsible for the death of as much as 50% of the population of Europe between the years 1347 to 1352.

Like all of our knowledge of history, what we know about the Black Death comes from those people who kept the records of that time, the literate people who lived in the towns or monasteries. Those records tell us much about the heavy toll the plague took on the people who lived in those communities. Unfortunately those records tell us very little about what was happening to the country people, the peasants, who made up more than 75% of the population in Europe back then.

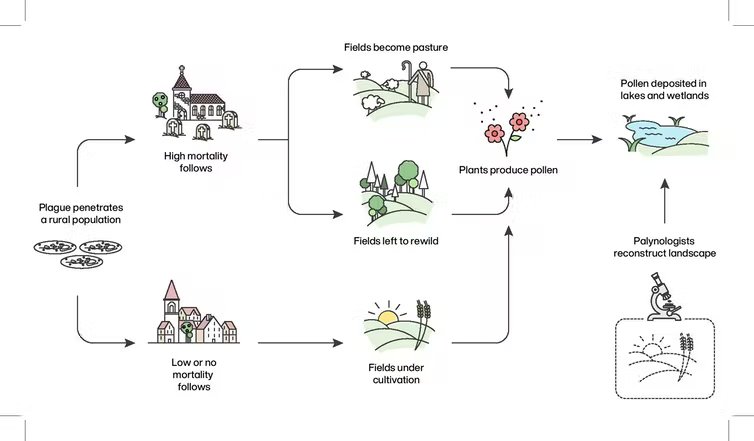

In order to correct for this urban basis in our knowledge of the effect of the Black Death the team from Max Planck used a new archaeological technique called Palynology, which is the study of fossil plant spores and pollen. The rational for the study was this, if the death rate due to the plague among the rural population was a high as it was in the cities and towns, about 50%, then large areas of once cultivated land should have reverted to wilderness in the years after 1352. Such a large scale change in the flora would be reflected in the kind of pollen that was deposited into the ground from that time.

The researchers collected pollen samples from over 1,600 sites spread throughout Europe and analyzed them. What they found was that the mortality caused by the plague varied widely from location to location, with some rural areas like those in Germany and Italy being hit just as hard as nearby cities while other localities suffered far less. Ireland, for example showed hardly any change at all.

These results correlate well with what epidemiologists are seeing today. Covid-19 may be a worldwide pandemic but how it effects each and every human being depends very much on local conditions where they live.

On a lighter note another team of archaeologists with the Max Plank Institute for the Science of Human History have unearthed an Old Stone Age site not 160 kilometers from present day Beijing in China. The site, which is in the Nihewan Basin to the northwest of the Chinese capital and has been given the name Xiamabei, was carbon dated to between 39,000 and 41,000 years ago and consists of a layer of remains that had been buried about 2.5 meters beneath the surface. During their excavations the archaeologists found and removed 380 small stone tools and artifacts along with 430 mammal bones.

The site was also identifiable by several artifacts that had been stained red by the mineral ochre, which is known to have been used by many primitive cultures as a dye because of its resemblance to the colour of blood. The Xiamabei site is the oldest ochre culture site to have been found in the Far East but the pigment is known to have been used in Europe and Africa as long ago as 300,000 years.

According to co-author Shixia Yang, a scientist with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, “The remains seemed to be in their original spots after the site was abandoned by the residents. Based on this, we can reveal a vivid picture of how people lived 40,000 years ago in eastern Asia.”

One big question left unanswered by the investigation so far is exactly what kind of human beings lived at the Xiamabei local. 40,000 years ago the residents could have been modern Homo sapiens but they could also have been either Neanderthals or Denisovans, the lack of any human bones makes it impossible to be certain. However a slightly younger, nearby location called Tianyuandong, lying about 110 kilometers away, has had remains of H sapiens identified there so the likelihood is that the Xiamabei site was made by our direct ancestors.

Just another couple of stories about the science of archaeology uncovering small bits of our past.