If you think about it the very first living creatures lived by just absorbing the nutrients in the water around them, not interacting at all with the other simple creatures nearby. After a few million years however some of those early life forms must have evolved to feed off of the dead remains of other creatures. And not too long thereafter, in geologic time at least, some creatures evolved to prey on their living fellows, and so the war of all against all (Bellum omnium contra omnes) began.

And many if not most of the anatomical design and features of those living things we call animals are intended to optimize their consumption of other organisms, plants in the case of herbivores and other animals in the case of predators. Today’s stories are all about some of the ways that evolution solved the problem of ‘Eat or be Eaten.’ As usual I will begin in the distant past and work my way forward in time.

Without doubt the ultimate form of ‘Eat or be Eaten’ would have to be cannibalism, where an animal literally preys upon and eats another member of its own species. In modern human civilization cannibalism is considered to be one of the most evil and horrible acts that a person can commit. It is worth considering however that cannibalism has been observed in more than 1,500 species, including we humans and whether we like it or not there are some pretty good evolutionary reasons for it.

You see by preying upon another member of your species you not only gain a meal but you are also eliminating a competitor for precious resources. For that reason cannibalism is often found in circumstances where food or other resources are scarce. Cannibalism does have its downside however because if you’re not careful you could be eliminating a relative or potential mate or even your own children and thereby reducing your share in the gene pool. And of course any species that practices cannibalism too much runs the risk of literally eating itself into extinction.

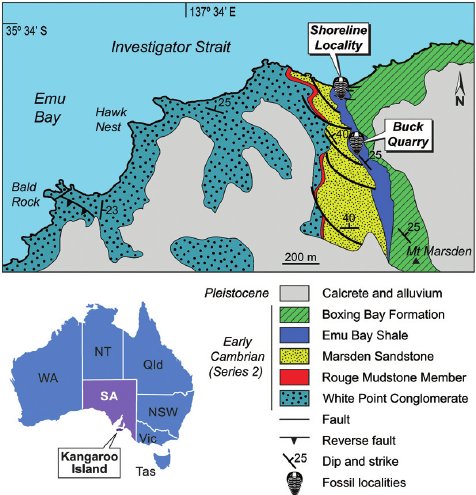

But just how long has cannibalism been a behavioral strategy used by living creatures? Think about it, solid evidence for cannibalism isn’t exactly easy to find in the fossil record. Now a paper published in the journal Paleogeography, Paleoclimatology, Paleoecology has announced that indications of cannibalism can be found at a 514 million year old Cambrian period fossil site on an island off the South Australian coast at a place called Emu Bay.

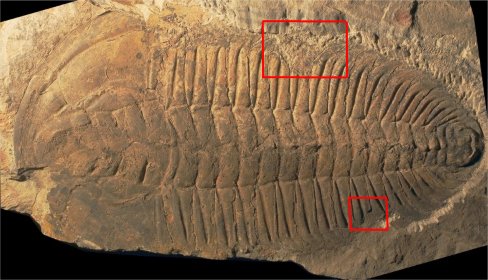

Emu Bay is one of those rare fossil sites where the preservation of specimens is so pristine that things like injuries and fecal material, called coprolites when fossilized, are easy to identify and analyze. The specimens that were found at Emu bay consisted primarily of two large species of trilobites Redlichia takooensis and Redlichia rex and many of the specimens were that were found had injuries that had healed. Now both trilobite species were large animals for that time, as much as 25 centimeters in length, so anything preying on them had to be at least as big as they were. That’s why the researchers, from the University of New England in Australia, believe that the cause of the injuries could have been another member of the same species.

Additional proof came from an analysis of the coprolites that were found, most of which were more than 10% the length of the trilobites themselves. Careful examination of the feces showed that they contained bits and pieces of shell material like the shells of the trilobites. More indication that the trilobites would, at least on occasion, chow down on their own kind. Between the injuries and the shell fragments in the coprolites the paleontologists feel they have a compelling case for the existence of cannibalism more than half a billion years ago.

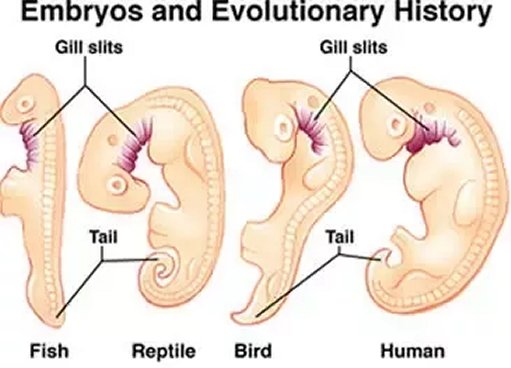

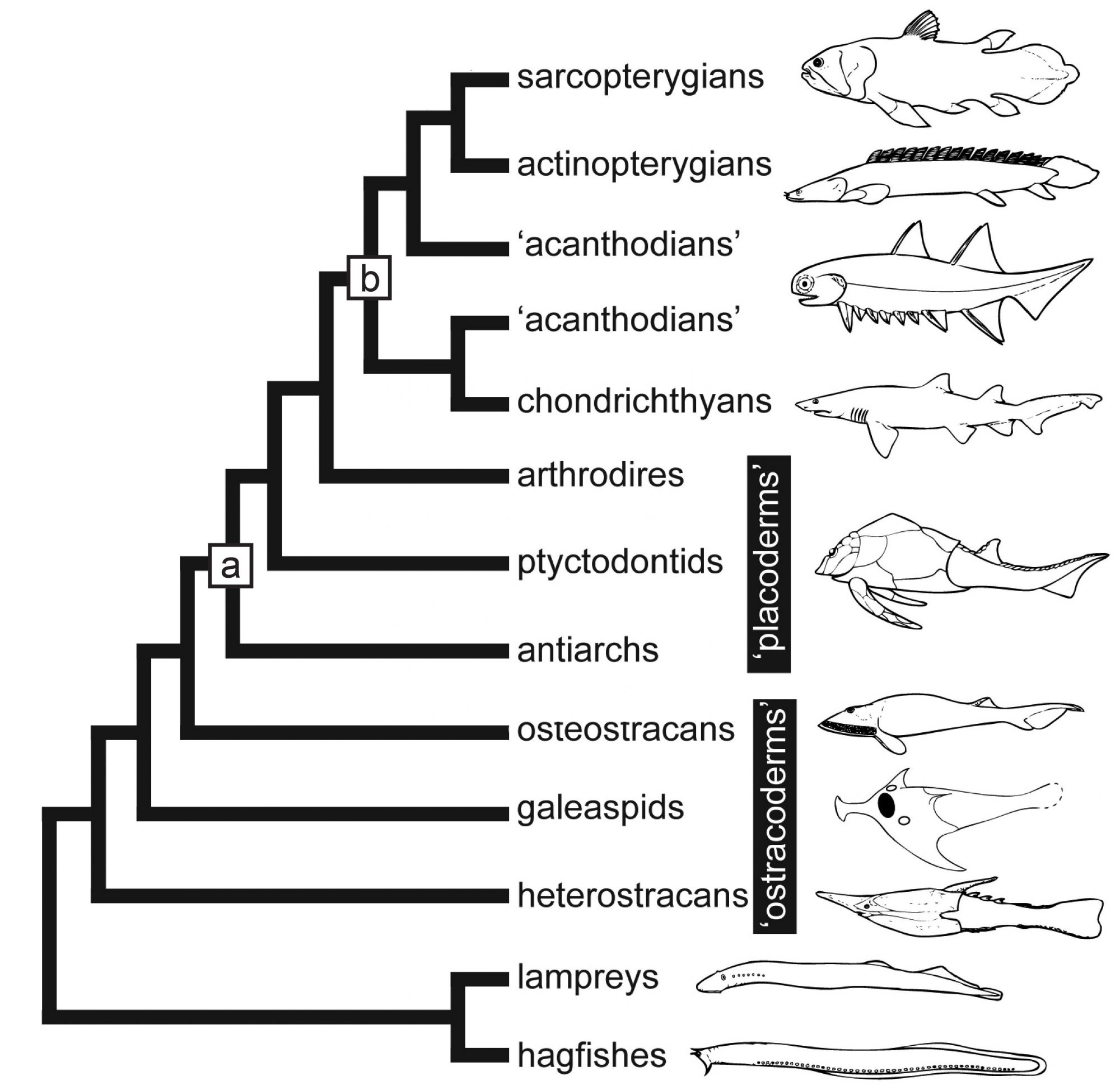

For vertebrate animals like we humans the need to feed efficiently led millions of years ago to the development of that structure that we all associate with eating, the jaw. The first jawed vertebrates appeared in the fossil record more than 400 million years ago as bones that had been used to support the gills of the first fish moved toward the mouth. Before long jaws had evolved into a wide variety of sizes and shapes that depended on both the type of food an animal ate and the method it used to feed.

(By the way the jawbones of modern vertebrates as they develop after fertilization follows the same developmental path that evolution did 400 million years ago during the Devonian period, this includes you. That is, about 5 weeks after fertilization you had gills, just like every other fish, and the four bones that developed to hold those gills in place then became your jawbone and the bones of your inner ear. The gills then simply disappear once the bones have formed since you no longer need them.)

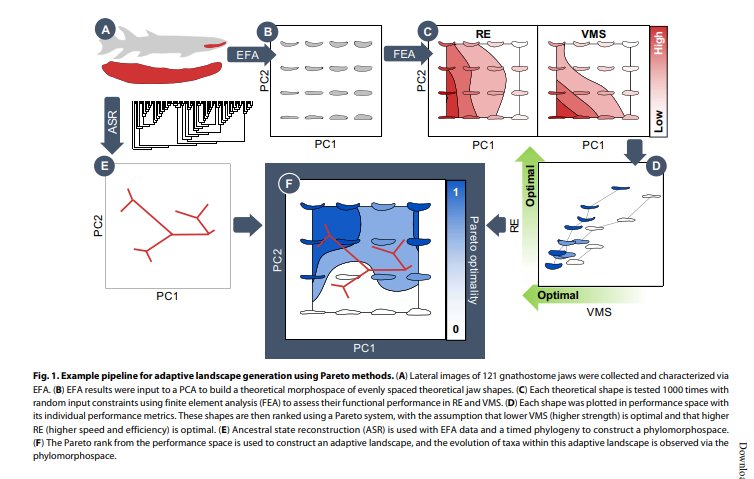

Now a new study has been published in the journal Science Advances that examines the variety of jaws that evolved so quickly back in the Devonian period. What the researchers at the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences found was that, despite all of the different sizes and shapes of jaws that evolved 400 million years ago there were two factors that predominated, speed and strength, and these two factors often opposed one another.

Think about it, a predator certainly needs a quick jaw in order to seize its prey before it can get away but if the jaw becomes too quick it can also become weak and brittle and a broken jaw is a virtual death sentence for any animal. So there has to be an evolutionary trade off between speed and strength in order for a predator to be able to successfully grab its dinner without any chance of it injuring itself.

A similar argument can be made for a herbivore, the animal needs a quick jaw to be able be bite off as much food as it can as quickly as it can, because remember plant material usually has a lower energy content. Then the plant eater usually has to grind their food in order to get all possible nourishment out of it, and that requires a good strong jaw.

The researchers used data about jaw size and shape from all of the known early jawed fishes and developed a computer model to compare each for speed and strength. They also included a few theoretical jaw shapes in their analysis. The results of the model clearly showed just how quickly the optimum blend of quickness and strength evolved.

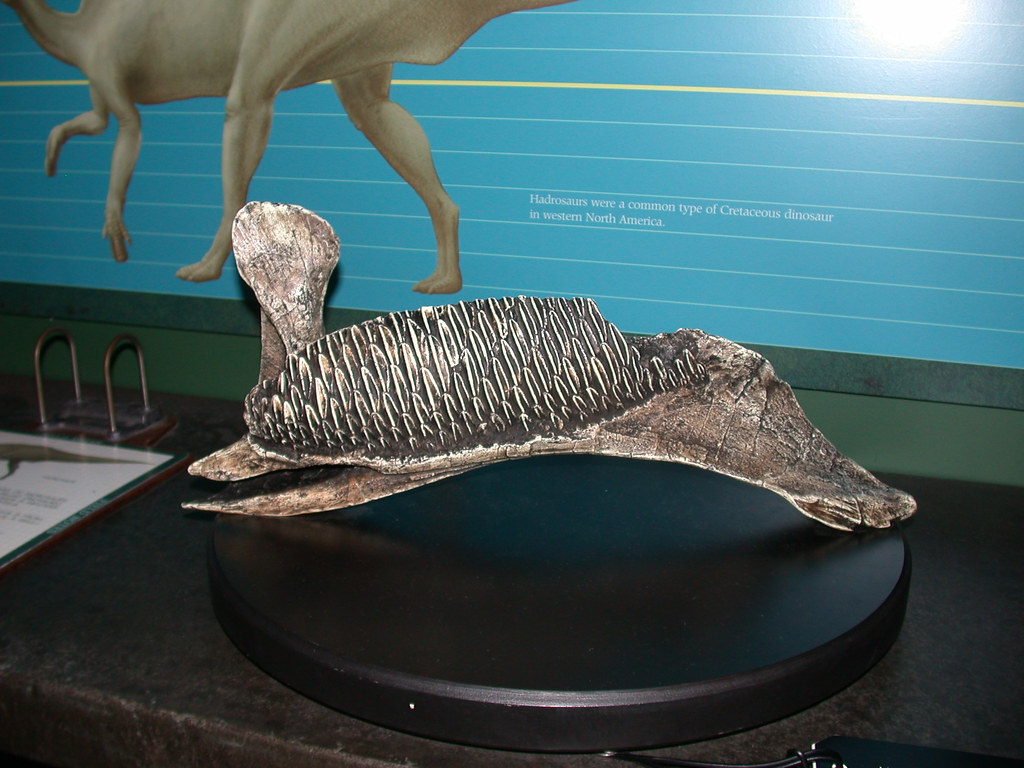

Now the jaw of a predator is certainly an offensive weapon and in order to protect themselves from predators many herbivores evolve some kind of defensive armour. One of the best known examples of such defensive body evolution is the family of dinosaurs known as the stegosaurs, with Stegosaurus itself having the characteristic two rows of bony plates along its back and long, sharp spikes on it tail that make it a tough meal for any hungry theropod.

Stegosaurs date from the middle Jurassic period to the early Cretaceous period, 160 million to 100 million years ago but their early evolution is unclear. Now a new specimen from the Chongqing region of China may hold some answers. Dated to about 168 million years ago the animal, which has been named Bashanosaurus primitvus, is the oldest stegosaur from Asia, and perhaps the oldest ever found anywhere.

In fact the animal was given the species name primitvus because of the peculiar, primitive set of characteristics it possesses. Smaller than other known stegosaurs, with thicker more narrow plates along its back B primitvus also had spines sticking out to the side of its shoulders. These features make B primitvus look quite different from other stegosaurs but at the same time it looks quite similar to other types of armoured dinosaurs like the first ankylosaurs that evolved about 20 million years earlier.

The paleontologists from the Chinese Bureau of Geological and Mineral Resource Exploration and Development along with the Natural History Museum of London who discovered and described Bashanosaurus hope that the fossil will shed light on the evolution of the stegosaurs. In any case the fact that armoured dinosaurs evolved so quickly, and diversified so rapidly is just the flip side of jaws and claws in the eternal struggle to ‘Eat or be Eaten’.