Many creatures in the natural world build structures, Bees build their hives, many birds build nests and Beavers build their lodges. Human beings however have rebuilt the world with all of our structures. It’s not surprising therefore that much of the work of archaeologists concerns human structures, how and why they were built.

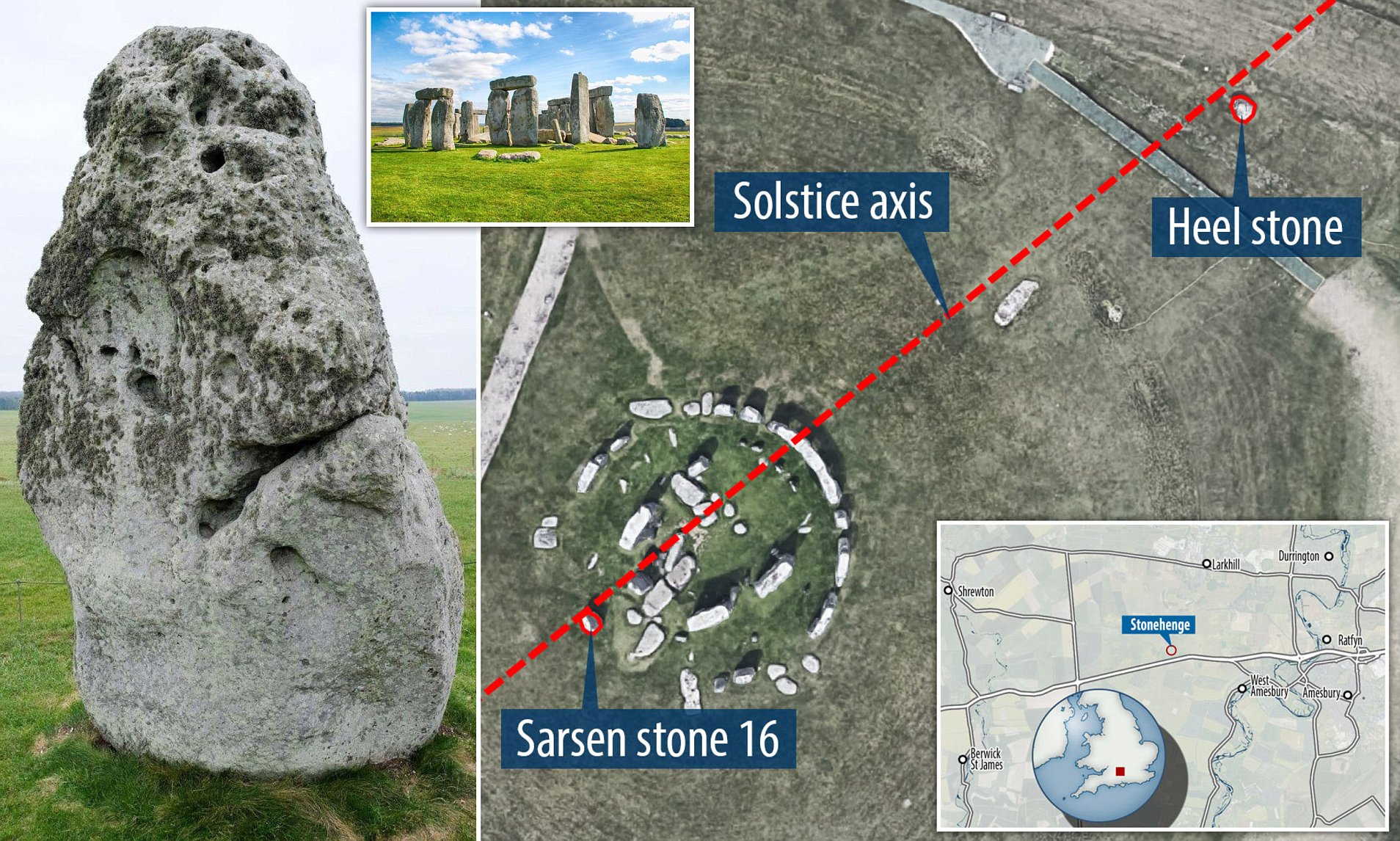

The first structure I’ll discuss today is a very well known one, perhaps the best known of all the prehistoric structures, Stonehenge in England. Much has already been written about this most famous of stone circles so I’ll just mention a few points of importance for today’s story.

Begun about the year 2200BCE Stonehenge was initially a circular trench dug into the soil with the excavated earth forming a circular henge inside the trench. It wasn’t until some 500 years later that the first stones were brought to the site and placed inside the earthen ring. These first stones are known as ‘Bluestones’, each weighing about 5 metric tonnes that were brought from the Mynydd Preseli region of western Wales, a full 290 kilometers from Stonehenge. See my post of 27 February 2019. How stone aged men managed to transport these large stones such a great distance is still a subject of controversy.

The larger ‘Sarsen Stones’, some weighing as much as 55 metric Tonnes, were brought to the site around the year 1500 BCE. While these massive rocks came from a much closer location just some 25 kilometers to the north bringing them to the Stonehenge site must still have required the cooperation of hundreds if not thousands of people indicating a society with considerable organization.

Several of the individual stones at Stonehenge have been given special names such as the Heel stone, which sits away from the other stones near the entrance to the original, and the slaughter stone, so named because early archaeologists thought it could have been used for human sacrifice. Both of these stones are Sarsen stones.

One of the Bluestones also has a special name, the Altar stone, so named because the other Bluestones seem to orient towards it as if it were the place where certain ceremonies were enacted. Now a new study by researchers at the Department of Geography and Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth University in the UK have questioned whether the Altar stone is in fact a Bluestone after all. For one thing, although the Altar stone is about the same size and shape as the Bluestones the others are primarily igneous rocks while the Altar stone is made of sandstone. Now there are sandstone deposits near the quarry in Whales were the Bluestones came from and it has long been thought that was the Altar stone’s source.

The new study conducted several different analysis of the material of the Altar stone including Ramen Spectroscopy, XRF analysis, optical petrography and SEM-EDS analysis. What the researchers found was that the Altar stone had a significantly higher level of the element Barium than the stones from the Welsh quarry, so it definitely did not come from the same place as the other Bluestones.

Where did the Altar stone come from, no one knows. So now the hunt is on to try to find the geographic source of the Altar stone. At the same time archaeologists now have to try to understand why that particular stone, from wherever it came from, was brought to Stonehenge. Now we have yet another mystery to add to all the mysteries surrounding Stonehenge.

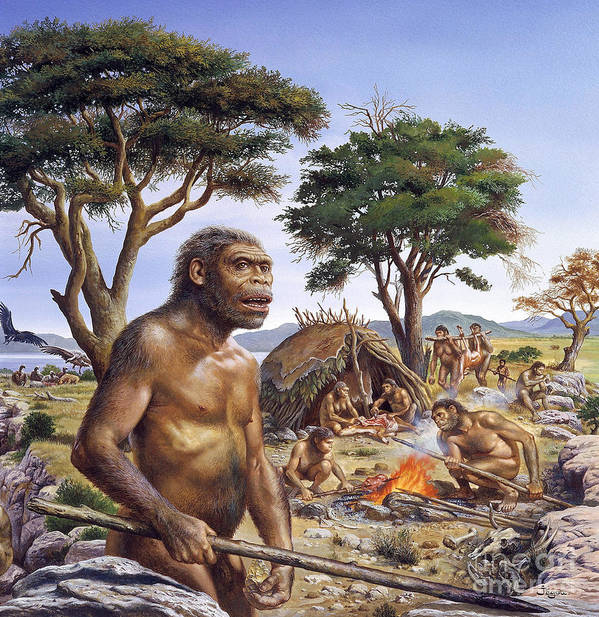

The second structure in the news recently may not be as famous as Stonehenge but it is certainly much older, in fact at an estimated age of 475,000 years old it may be the earliest wooden structure known have to been built by humans. In fact the structure wasn’t built by our species Homo sapiens but probably by our ancestral species Homo erectus.

The wood was discovered in the sands at the bottom of the river beneath the Kalambo falls in Zambia not far from the border with Tanzania by archaeologists from the University of Liverpool and the University of Aberystwyth. The location had been studied by archaeologists ever since the 1950s and pieces of wood that shows signs of having been worked by humans have been found there before. Those artifacts included sticks used for digging, the hafts of spears and wood used to build fires. The wooden pieces from the riverbed were preserved because they had been essentially ‘pickled’ by the acidic water of the river.

The new find however consists of two much larger wooden logs, each about 2m long, which had been worked by stone tools in such a way as to fit together in a ‘T’ shape. The archaeologists who found the logs think that the wooden T probably served either as a foundation for either a dwelling of some kind or more likely an earthen platform from which to fish in the river.

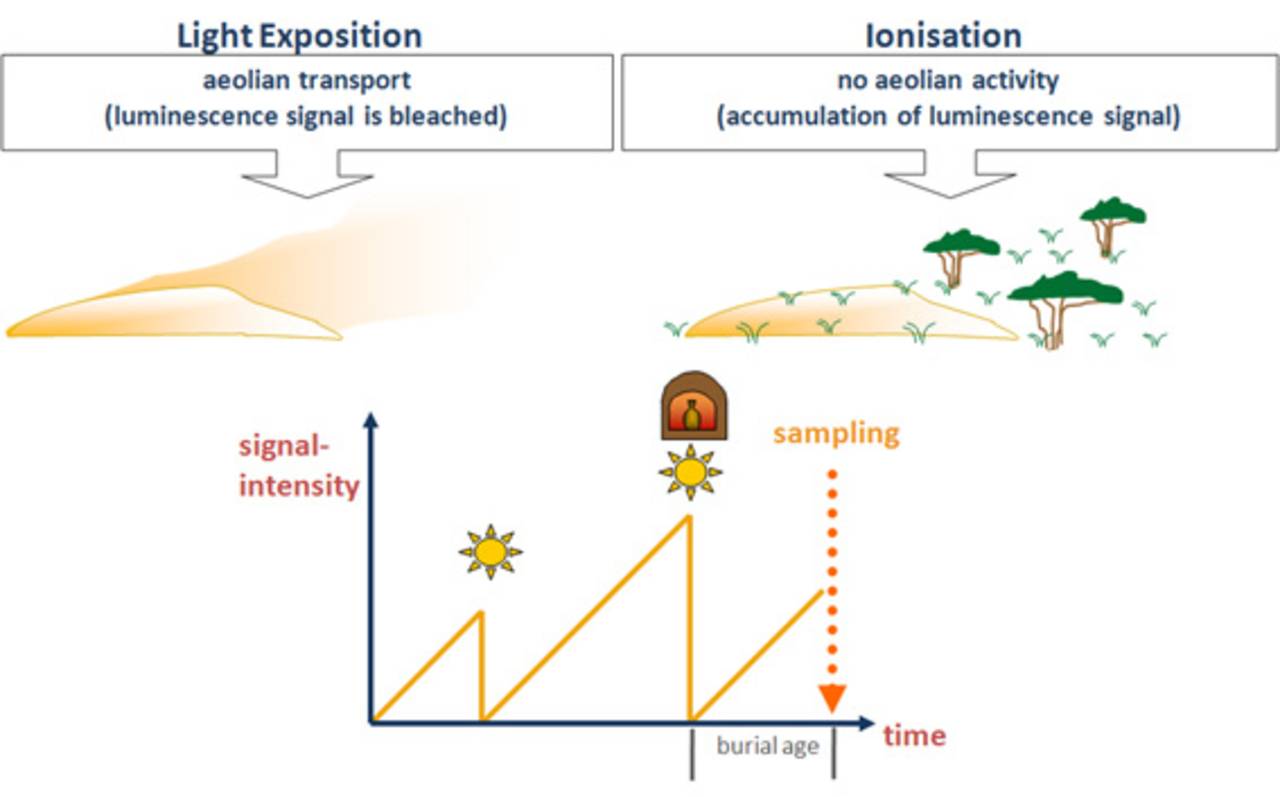

Unlike earlier pieces of wood from beneath the falls the team was able to get a more precise date on the logs by using a new dating technique known as luminescence dating. This technique depends on the fact that grains of sand will pick up natural radioactivity from the environment over time. By heating up those grains and analyzing the light they emit their age can be determined. Luminescence dating is quickly becoming an important tool in archaeology and paleontology because it is able to measure the age of objects that are too old to be determined by Carbon14 but too young to use Potassium-Argon dating.

The find in Zambia pushes back in time the date of the first known use of wood to build structures showing that even our remote ancestor were capable of innovation and invention.