When most people think of the kind of tools that an Archaeologists use in their study of ancient people the first thing to come to mind would probably be either a shovel or a trowel. After all, archaeology is about digging up the lost artifacts from bygone civilizations isn’t it?

Well in my post today I’ll be discussing a couple of studies that employ the latest technological tools that archaeologists now have to help them learn about past cultures. As usual I’ll start with the oldest story and work my way forward in time.

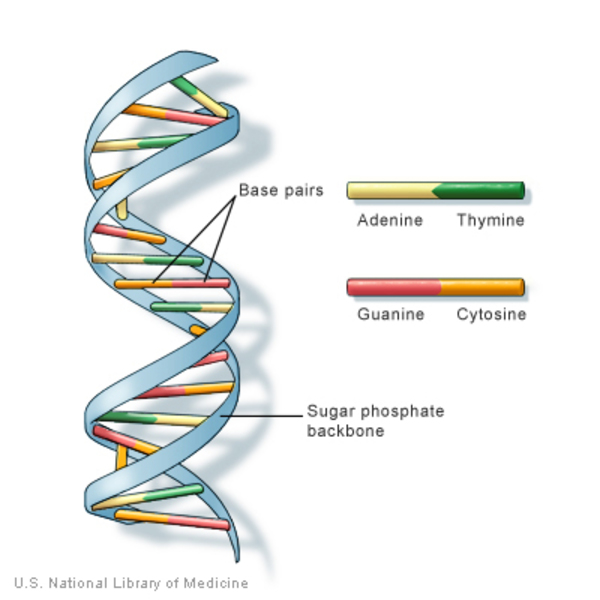

Surprisingly enough over the last few years DNA has become one of the most important tools in archaeology, see my posts of 10 August 2019, 22 July 2020 and 14 January 2020 for example. The ability to demonstrate, or refute, genetic connections between two or more archaeological sites has answered many long disputed questions about the past.

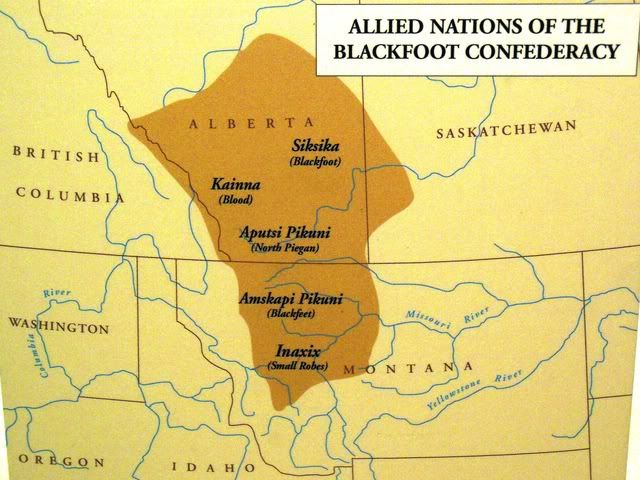

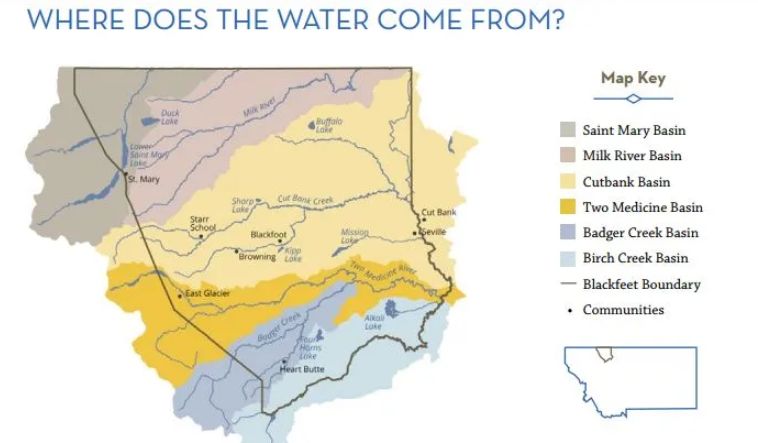

Now a new study published in the journal Science Advances has used both ancient and modern DNA to reveal some surprising facts about the genetic relationships of the indigenous people of North America, in particular the people of the Blackfoot Confederacy. Historically these tribes lived in the northern plains of the US and southern Canada between the Rocky Mountains and the Great Lakes. According to Blackfoot legends those plains had been their home as far back as the end of the last ice age more than 10,000 years ago. These legends have also been supported by archaeological evidence collected from the region.

The new study compared DNA taken from seven ancient burials unearthed in the region inhabited in the Blackfoot to that of six modern day members of the Blackfoot Nation. What the researchers, led by Dorothy First Rider of the Blood First Nation Organization in Canada discovered was a high proportion of shared alleles between the ancient and modern samples, strong evidence for a direct genetic relationship, even after thousands of years. Comparisons were also made to nearby native peoples. These comparisons indicated that the Blackfoot / Blood native nations separated as long ago as 18,000 years while the separation of the Blackfoot and Athabascan peoples occurred about 13,000 years ago.

The fact that the Blackfoot Nation may have remained a homogenous group living in the same place for so long may even have legal repercussions. That’s because the Blackfoot legacy has for decades been at the center of numerous lawsuits over land and water rights in the ancestral Blackfoot homeland. The DNA evidence detailed in the study may help the original inhabitants to have a greater say in how those lands are treated today.

Another high tech tool that is starting to find applications in archaeology is Artificial Intelligence or AI for short. Computer algorithms that can learn from their mistakes are now appearing in a wide range of research fields from driverless cars to deep fake images to deciphering ancient cuneiform tablets. See my post of 16 September 2023.

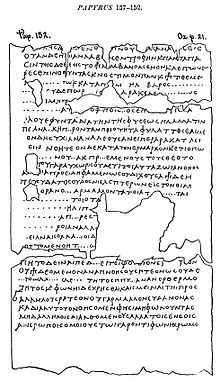

Now a contest, open to literally anyone has succeeded in using AI to reveal the text written on a 2,000 year old papyrus scroll that was charred beyond recognition, but still kept in one piece, by the eruption of Vesuvius that buried the town of Pompey. The scroll is one of hundreds that were excavated from a luxury villa in the nearby town of Herculaneum back in the 18th century.

In the more than 200 years since their discovery many attempts had been made to read the scrolls, all without success and some of which caused considerable damage to the fragile remains of ancient writing. Then, in 2019 Brent Seals, a computer researcher at the University of Kentucky developed software that could virtually unwrap the outer layers of two of the scrolls using the scans produced by Computed Tomography (CT). Those scans by themselves were still unreadable however because the density of the ink used on the scrolls was the same as the papyrus itself. CT scans generate 3D images of the inside of objects by measuring the difference in densities of the materials of which the object is composed.

It was at this point that Seales thought of the idea of a contest among AI researchers in the hope that someone, or some team could take the scans he had produced and finally decipher the text of the ancient scrolls. With the financial assistance of Nat Friedman, a well known Silicon Valley tech entrepreneur, Seales raised $700,000 dollars and announced the Vesuvius Challenge. The criteria set for the winners was to decipher at least 4 passages of at least 140 characters each.

Three students, Luke Farritor, a undergraduate computer science major at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, Youssef Nader, a Ph.D. candidate from Egypt who is studying in Berlin along with Julian Schilliger a robotics student at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich pooled their respective talents in order to decipher 15 columns of text, about 15% of the entire scroll, enough to win the prize.

The scroll turned out to be a treatise on pleasure based upon the Greek Epicurean school of philosophy. Specifically the writing discussed the pleasures of music and food spiced with capers. The ability of the AI programs developed by Seales, Farritor, Nader and Schilliger to decode the blackened remains of the scroll has given archaeologists hope that at least some portions of the other 200 Herculaneum scrolls may also be deciphered.

Not only that, but the ancient Roman villa in which the scrolls were discovered has never been completely excavated. Large sections of both Pompey and Herculaneum have been intentionally left for future archaeologists, with more advanced technology to study. Who knows what other wisdom from the classical Roman period lie waiting to be unearthed and hopefully read?

Just two examples of how new technology, new tools can bring new discoveries that allow us to better understand the ancient world.