Everybody knows that our environment is in trouble. The waste and pollution generated by eight billion human beings is choking the planet, producing changes that have already caused the extinction of hundreds of species, and may lead to our own. If we are going to preserve the environment we cannot just return to a simpler, less polluting level of technology, let’s say the 18th century as an example. As I said there are eight billion of us now and horsepower, waterwheels and ox-drawn plows will not sustain such a large population. Instead we must use our technology to develop solutions to the problems that ironically we used technology to cause.

Recently there have been three new technological breakthroughs, inventions if you like, that may play an important role in saving our planet. At least I hope so.

In many ways plastic is actually harmless. It’s neither poisonous nor cancer causing. In fact it has many excellent qualities, it has countless uses and it’s so cheap that we use it in countless ways. Ironically it is the fact that plastic is so useful, and cheap that makes it so great a danger. We manufacture so much of it and despite what the plastics manufactures tell us we don’t recycle more than a very few percent of what we make. The truth is that, aside from plastic 2-liter bottles, most single use plastic items, like plastic bags, utensils and straws, are not even made of the right kind of plastic to be recycled. All of those items, and many others just accumulate in our waste dumps which, since plastics don’t decay, are becoming an ever bigger problem on both the land and in the sea.

To solve that problem chemists have for many years been searching for a kind of plastic, technically a polymer, that can easily, and cheaply be broken back down into their constituent parts, chemically known as monomers. These reconstituted monomers could then used to create new polymers, new pieces of plastics over and over again.

A team of researchers from the United States, China and Saudi Arabia has recently announced the development of just such a polymer plastic, which they call PBTL. According to the announcement, which appeared in the journal Science Advances, PBTL has all of the desirable qualities of current plastics but in the presence of a catalyst PBTL breaks down readily into its original monomers. After testing through multiple build ups and breakdowns the teams concluded that there was no reason that the cycle could not be carried out over and over again, that they have succeeded in developing a plastic that is designed to be recycled.

Of course there is one caveat, in order to make the optimal use of PBTL’s reusability it must be separated not only from non-plastic waste but from all other kinds of plastic. That means more sorting, more manpower required in the recycling effort and that means more cost. What’s needed therefore is some recognizable way to distinguish PBTL from everything else. It would also be helpful if all plastic items were manufactured from PBTL but that may be difficult to accomplish since there are so many plastic manufacturers.

Still it is a step in the right direction. With PBTL we now can recycle all of our plastics, if we have the will to do so.

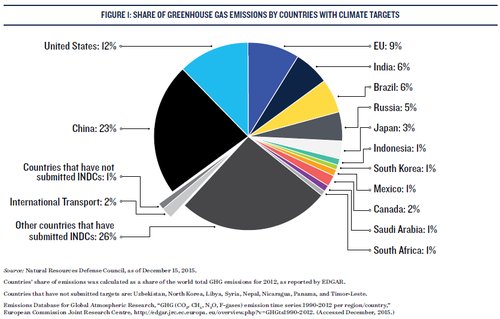

As bad as the problem of plastics is, and even greater threat to our planet must surely be the enormous amounts of CO2 that we have been releasing into the atmosphere. And to make matters worse at the same time we are cutting down the Earth’s forests that are the best way of removing that CO2 from the air. The resulting buildup of greenhouse gasses is the direct cause of global warming and the attendant changes in climate.

So if forests and other vegetation are one way of getting CO2 out of the atmosphere shouldn’t we be planting more trees and other plants. Of course there are people trying to do just that, however those efforts have so far been unable to even keep pace with deforestation let alone bring down the level of greenhouse gasses.

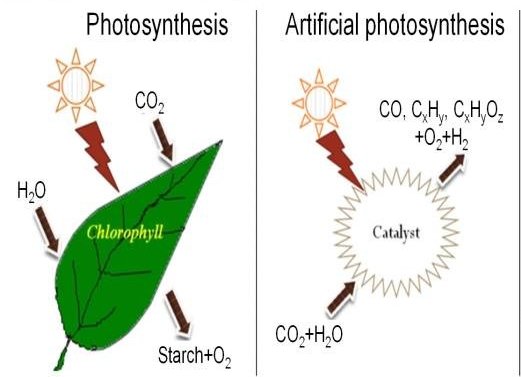

So scientists have been trying to develop an ‘Artificial Leaf’ which, like a real leaf, would use sunlight and water to covert CO2 into a usable fuel. Such a technology would mimic photosynthesis and in large scale operations could provide the energy we use reducing if not eliminating our dependence on fossil fuels.

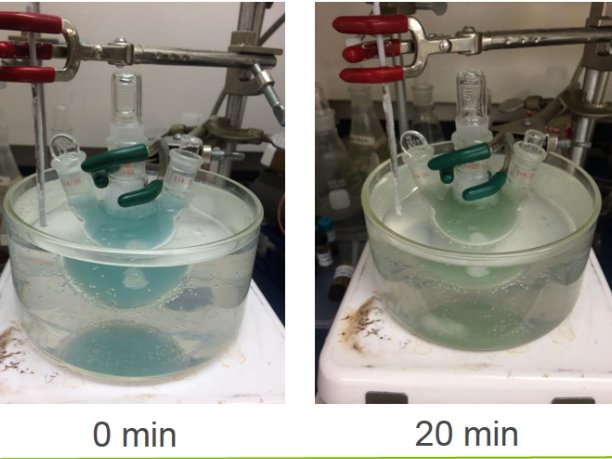

Some of the most advanced research toward an artificial leaf has come from the Department of Chemistry at Cambridge University where Professor Erwin Reisner leads a team of chemists who last year succeeded in producing a device that converted CO2 into the fuel syngas, a fuel that is not easy to store for long periods of time. Another problem with the device was that it was constructed from materials similar to those in ordinary solar cells, making the device expensive to scale up into a large scale power plant.

Now the team at Cambridge has developed a new artificial leaf that is manufactured on a photocatalyst sheet, a technology that is capable of being scaled up much more easily, and therefore more cheaply. Also the end fuel produced by the new ‘leaf’ is formic acid which is more storable and can be converted directly into hydrogen, as in a hydrogen fuel cell.

The Cambridge team still has more work ahead of them; the efficiency of the entire system needs to be improved for one thing. However it is quite possible that in just a few years we may have a new form of solar technology that not only produces energy but actually removes CO2 from the atmosphere.

Of course we already have a both solar and wind technologies that are actually producing a sizable fraction of our electricity. One big problem that has limited the usefulness of both solar and wind power is that the energy they generate varies significantly. When it’s a sunny day or if there’s a good breeze they produce a lot of energy that somehow has to be stored so it can be used at night or an a calm day. Most often that energy is stored in old-fashioned chemical batteries, a technology that has hardly improved in the last 100 years.

As any owner of an electric car will tell you batteries absorb their energy slowly, taking a long time to charge up. Not only that but batteries tend to be heavy, costly and have a limited useful lifespan, a very large number of problems for such a critical component in modern technologies.

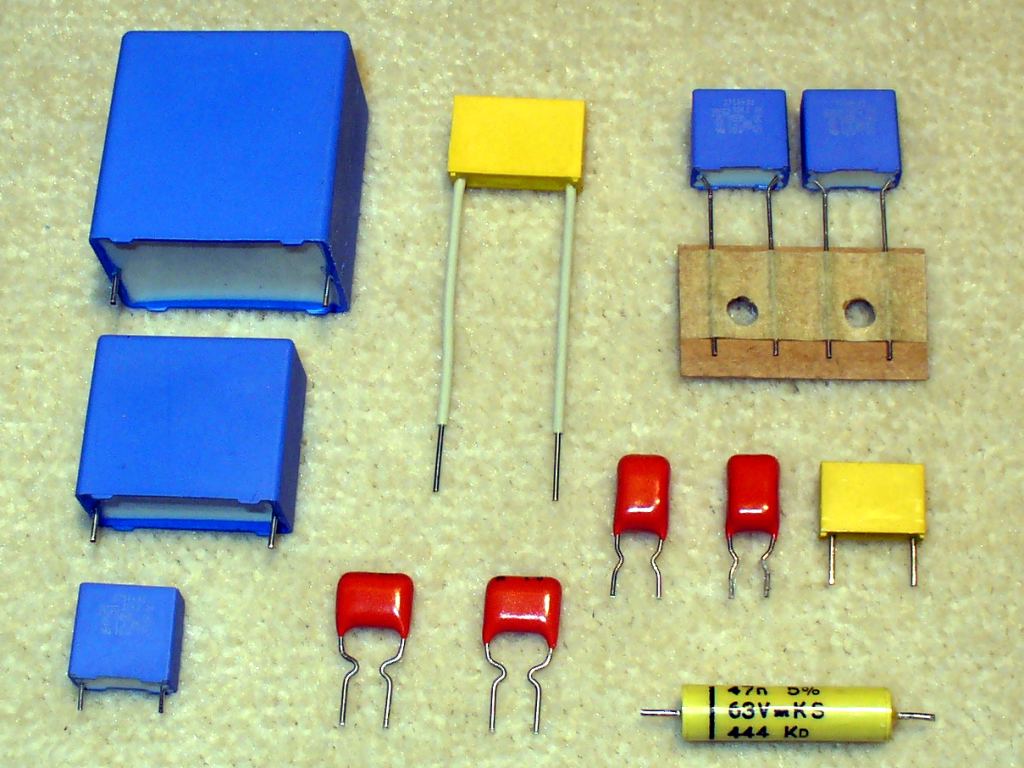

There is another energy storing electronic device that is cheap, lightweight, can be charged and discharged thousands of times, not only that but they can absorb or discharge their energy very quickly. They are called capacitors, descendents of the old Leyden jar and even if you’ve never heard of them you own hundreds of them in your cell phones, TVs, computers and other electronics. Capacitors, the very name comes from their capacity to store electricity, are superior to chemical batteries in every way except one, they can’t store nearly as much electrical energy as a battery can.

As you might guess there are engineers working on capacitor technologies in the hope of increasing the amount of energy they can store. One such group is working out of Lawrence Berkeley National Labouratories and is headed by Lane Martin, a Professor of Materials Science at the University of California at Berkeley. Taking a common type of commercially available capacitor known as a ‘Thin Film’ capacitor Martin and his associates introduced defects into the material of the thin film known as a ‘relaxor ferroelectric’.

Now ferroelectric materials are non-conductive which allows the capacitor to hold positive charges on one side of the film and negative charges on the other, that’s how the energy is stored. The higher the voltage across the thin film the more energy is stored but if the voltage gets too high the film breaks down, the energy is released and the capacitor is destroyed.

The engineers at Lawrence hoped that by adding the defects to the thin films they could increase the voltage the capacitor could withstand without breaking down. Doubling the voltage by the way would actually increase the energy stored by a factor of four. The team used an ion beam to bombard the ferroelectric material creating isolated defects in the film and the first results of testing have shown a 50% increase in the capacitor’s efficiency along with a doubling of the energy storage capacity.

As with the other two new inventions described in this post, capacitors that can store twice as much energy are not going to solve all of our environmental problems, but they’ll help. That’s the takeaway from all of technology developments I’ve discussed; each one is a step towards solving our energy and pollution problems. We have the scientists who can find the solutions, do we have the will to use their work and save our planet before it’s too late?