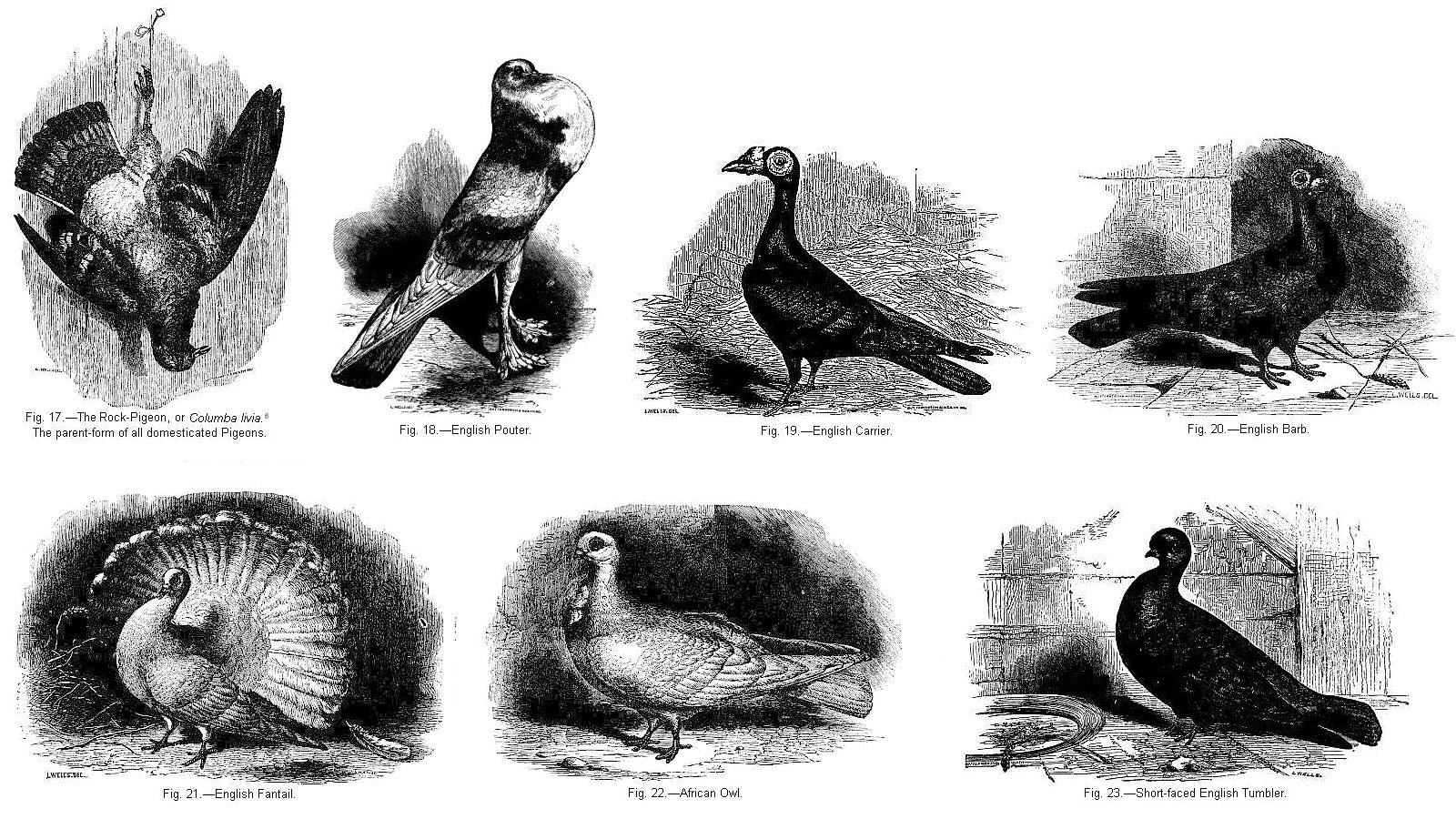

In his book ‘On the Origin of Species’ Charles Darwin coined the phase ‘Artificial Selection’ to describe the way we human beings breed those of our domesticated animals who possess those traits that we find desirable and wish to propagate. By selectively breeding our pets and livestock we have succeeded in generating an enormous number of different breeds of dogs, cats, cattle, sheep etc, etc. Botanists have used the same techniques to develop more productive and hardier stains of the plants we eat or the flowers we admire.

Several times Darwin contrasted this Artificial Selection with his ‘Natural Selection’. Both depend on the random mutation of genes to produce those changes in living creatures that produce new and different traits. But whereas we humans will directly favour those mutations with traits we desire, making certain they live longer and propagate more, in the natural world beneficial mutations give only a slight advantage. For example a Zebra colt with a mutation that enables it to run faster, a huge advantage for a zebra, could die in a drought or flood before it ever gets the chance to mature and pass on that beneficial mutation. This makes natural selection a much slower, more haphazard process than artificial selection.

Right now this planet is going though a large number of very rapid changes caused by the growth of our human population. Climate change, industrial pollution and the loss of habitat are just the three biggest problems that the other living creatures on Earth are having to adapt to. Problem is that they simply can’t adapt fast enough, natural selection is a slow process remember so instead of adapting what’s actually happening is that many species are going extinct. Every year more and more kinds of animals and plants just disappear because they aren’t able to evolve fast enough to keep up with the changes we are causing to the planet.

Wouldn’t it be nice if there was some way to use the faster speed of human directed artificial selection to enable species to change fast enough that they could adapt to all the changes around them. That’s the basic idea behind the new program of ‘Assisted Evolution’, to use our knowledge of genetics and selective breeding in order to help species that are in trouble to adapt more quickly to a changing world.

Currently a major effort is underway in both the United States and Australia to use assisted evolution to save each nation’s coral reefs. Over the last 20 years or so nearly half of the Great Barrier Reef and the Reefs around the Florida Keys have seen massive episodes of coral die offs due to increased ocean water temperatures and pollution.

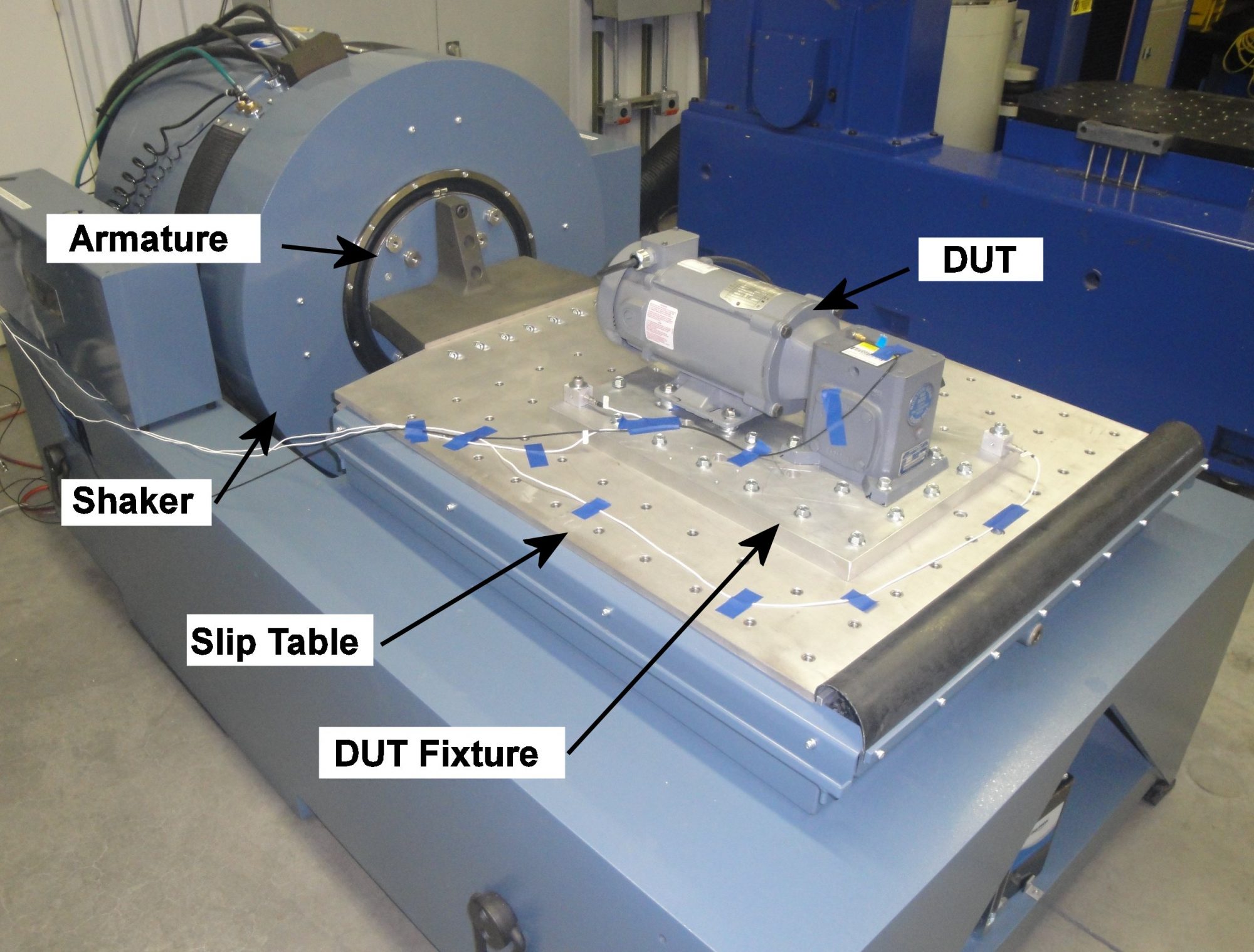

Scientists in both nations have been studying the various species and varieties of coral, subjecting samples in a labouratory to excessive temperature and pollutant levels in order to discover which can better withstand the higher than normal levels of stress. Those varieties that showed greater adaptability are now being grown in nurseries before being transplanted back onto injured coral reefs in the hopes that they will grow and help repair the damage.

This type of assisted evolution is known as ‘Stress Conditioning’, forcing individual specimens to endure high, but non-lethal levels of the environmental stress. Those individuals that survive best are then breed in large numbers to be returned to the wild to hopefully increase their species chance of surviving.

Australia is also the site of another effort using stress conditioning. In the centuries since Europeans first settled the land down under the native wildlife has suffered greatly from invasive European predators, feral cats in particular. Several species of marsupials, such as the lesser bilby and the crescent tailed wallaby have gone extinct primarily because of cats.

Because there are now simply too many cats to even try to eradicate them, researchers are attempting a different strategy to save other threatened species, exposing them to cats in controlled settings. Two large paddocks in the Australian Outback have been set up with a few hundred greater bilbies, a relative of the lesser bilby in one and a few hundred burrowing bettongs in the other. Five cats were then introduced into each paddock and allowed to prey on the native marsupials.

After several generations of the marsupials, during which time the number of cats was kept controlled; the offspring were placed in another paddock with members of their species that had not had the stress conditioning. Again a few cats were introduced and the ratio of kills for conditioned and naïve prey was measured. The naive marsupials suffered much more than their conditioned kin indicating that the conditioned bilbies and bettongs had become cat savvy a sign of hope that perhaps their species can learn to survive the harm done by invasive cats.

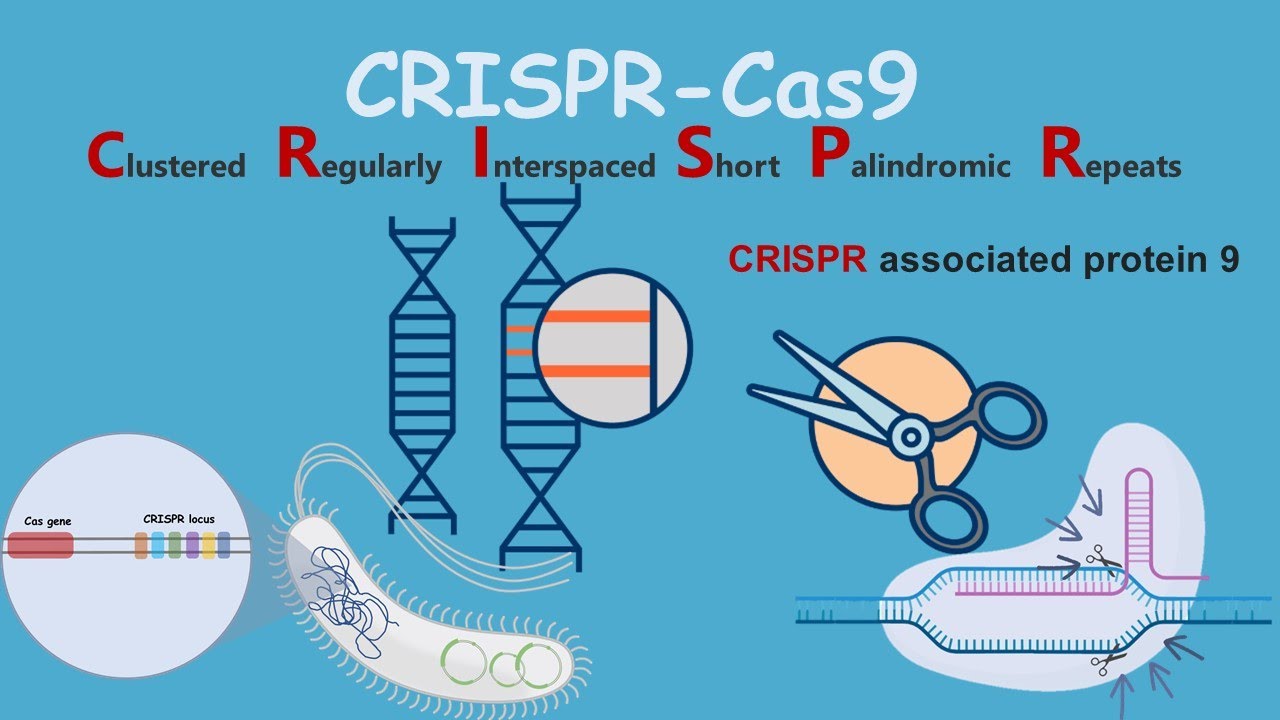

Another type of assisted evolution that is being tested in labouratories but not yet used in the wild is known as Assisted Gene Flow (AGF). In AGF the actual DNA of a threatened species is altered by a gene editor like CRISPR in order to change their anatomy to help them adapt to changing conditions. For example an animal whose environment is undergoing increasing drought conditions could be have genetic material from another species inserted into their DNA that enables it to better survive long periods of time with little water.

The technique of AGF is more controversial than stress conditioning however, as is the entire science of gene editing in general. The question of how many genes can be altered before you’re no longer saving the original species but a labouratory version of it comes into play. Indeed the whole question of trying to save threatened species by changing them is problematic.

Still, every year as more and more species become extinct the possibility of saving some species by helping them adapt to the changes we are causing is at least trying to mitigate the harm we’re doing.