I assume by now everyone out there has heard about the Solar Eclipse that is going to occur on April the eighth. That day the Moon will cross in front of the Sun completely blocking out the Sun’s light in the middle of the day. The celestial event will draw a line of totality across the North American continent traversing Mexico before passing through 13 states of the US with the show finally ending in the maritime provinces of Canada.

I’ve had my eclipse plans made for sometime now. I’ve got plane tickets and hotel reservations in a small town in Texas just to the east of Dallas. I won’t have to move an inch to see a full four minutes of totality, weather permitting that is. That’s always the big question with any rare astronomical event, whether it’s an eclipse or a transit or an occultation, will the weather be good enough so that you can see? So wish me luck and I’ll tell you all about it when I get back. (See my post of 24 August 2017 about the eclipse of 2017.)

Before I move on to my next story a word of warning about looking directly at the Sun at any time, not just during an eclipse. Yes, I know you’ve heard this all before, nevertheless get a good pair of eclipse glasses before April 8th and BE SURE TO USE THEM! I’m certain by now you’re as tired as I am about hearing the warnings but you’d be surprised at just how many people ignore those warnings no matter how many times they hear them. So, please get a good pair of eclipse glasses and use them when viewing the eclipse. By the way, the Sun is interesting to look at, WITH GLASSES, even when there’s no eclipse.

Some astronomical events last a little longer than an eclipse however, giving an observer chances on several nights to see it, and one of those may happen later on this year. The star system designated as T Coronae Borealis (T CrB) is known to astronomers as a repeating nova, that is a star system that periodically increases in brightness by hundreds or even thousands of times for short periods of time, usually around a month. Now we’re not talking about a supernova here, you know those massive stars that can end their brief lives in huge explosions that can outshine their entire galaxy for a month or so. Such stars can only explode once and then leave behind either a neutron star or a black hole. (See my post of 26 May 2021 for more information on Supernovas) Ordinary nova may not be as spectacular but some nova can repeat their brilliant displays.

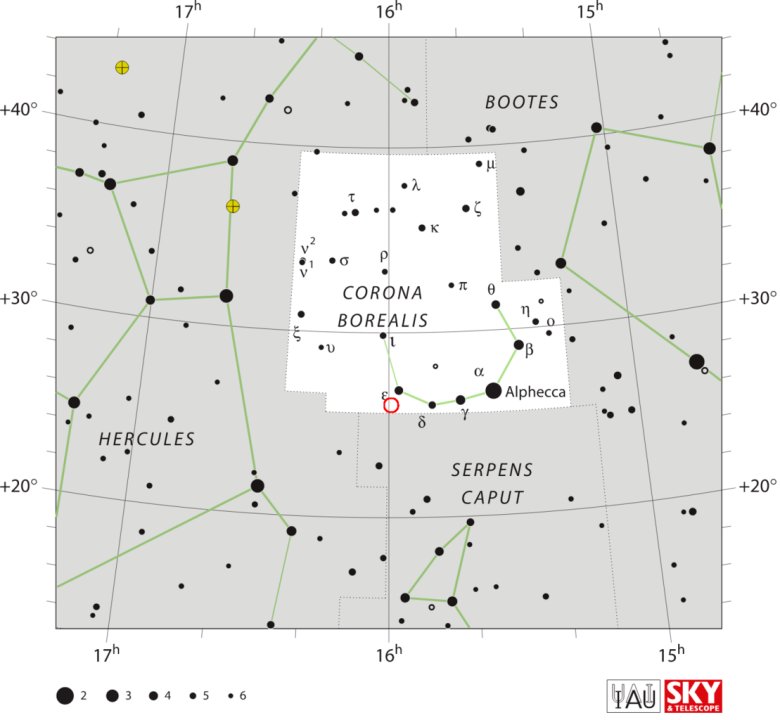

T Coronae Borealis is a double star system that lies about 3,000 light years away in the constellation Coronae Borealis or the Northern Crown. The system consists of a white dwarf star that is closely orbited by a red giant. The two stars are in fact so close that the white dwarf is stealing material from the outer envelopes of it companion. Eventually enough matter falls onto the surface of the white dwarf to trigger a fusion eruption, causing the dwarf to shine thousands of times brighter, for as long as the eruption lasts.

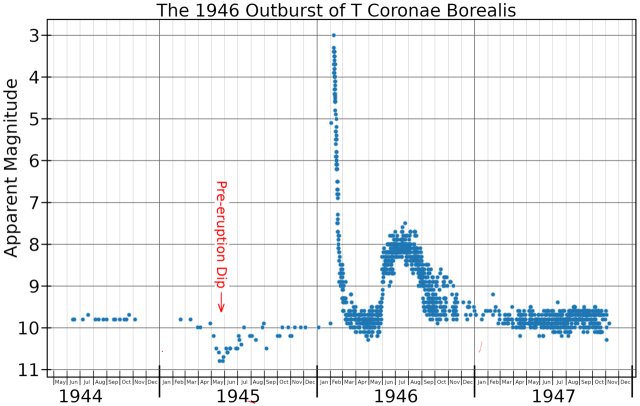

T Coronae Borealis is one of only five known periodic novas in our galaxy and has been observed to erupt every 80 years for the last several centuries. The last time the system went nova was back in 1948 so it’s about due. The best estimate is that the system will erupt sometime between now and September, but of course it’s always hard to make accurate estimates about something that is happening 3,000 light years away.

Normally T Coronae Borealis shines at a magnitude of +10, far to dim to be seen with the naked eye, even with really dark skies our human vision cannot see anything higher than a +6. As I said however as a nova the star could shine thousands of times brighter, reaching up to perhaps a +2, about the same level of brightness as Polaris the north star and therefore quite visible, even with city lights. And T Coronae Borealis should remain that bright for at least a week giving everyone in the northern hemisphere at least several chances to see this rare event.

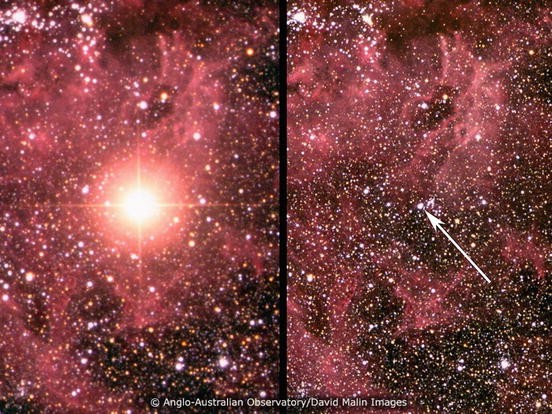

Speaking of supernovas the last such giant event in our galaxy happened back in 1987 when a star in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy to our Milky Way, exploded. SN 1987A as it is known was the closest supernova to Earth since the time of Kepler back in the late 17th century and the first, and so far only, supernova for which we actually have a picture of the star before it exploded. (Again see my post of 26 May 2021))

Now when a star goes supernova the outer layers of the star are ejected out into the interstellar medium seeding that medium with the heavier elements that had been generated in the star. The star’s inner core however collapses inward becoming either a neutron star or a black hole.

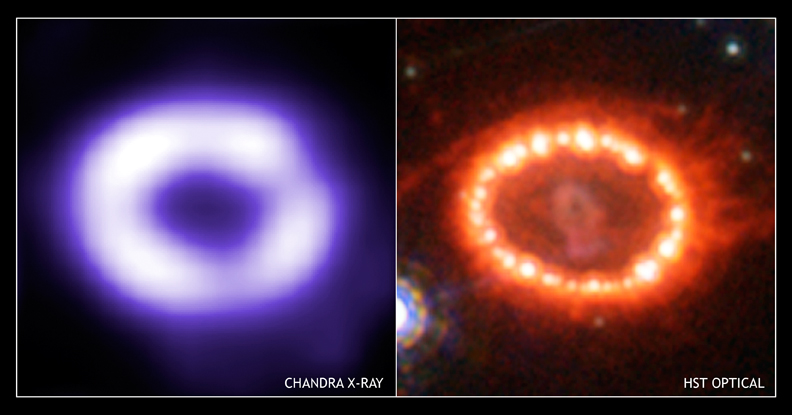

Now ever since the explosion of SN1987A dissipated astronomers have been searching for any sign of the compact object that was left behind. Astronomers know of many such objects known as pulsars like the one at the heart of the Crab Nebula supernova remnant. Thirty-five years of searching however failed to find any trace of whatever was left of the star that became SN1987A.

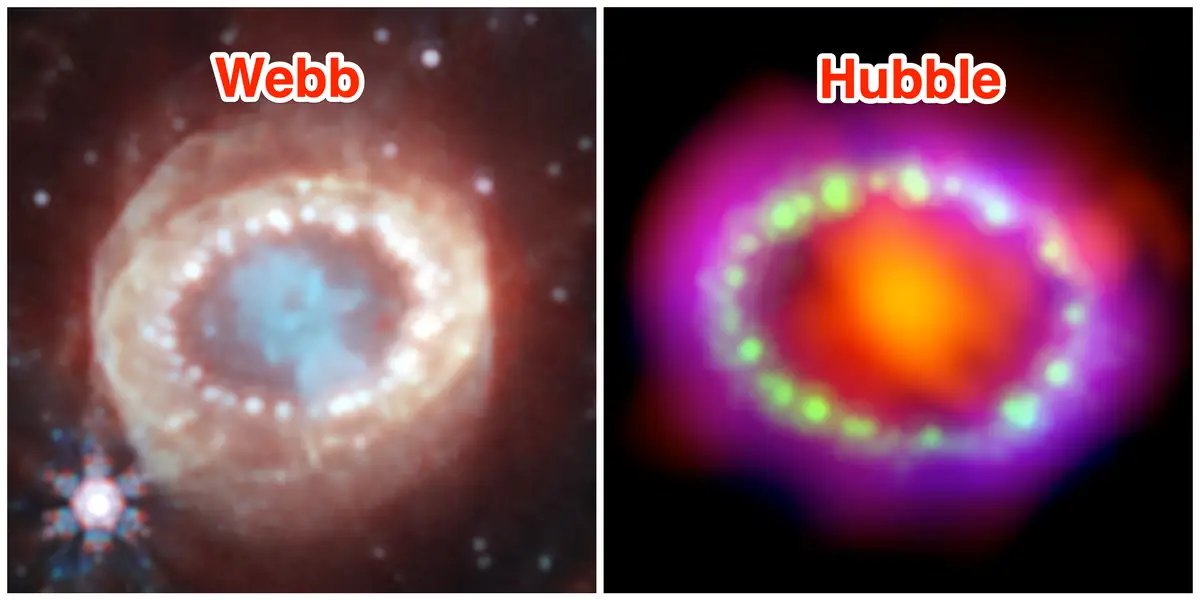

Until now, now new observations by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have detected light coming from argon and sulfur atoms surrounding a neutron star at the heart of the supernova remnant. The kind of light Webb detected indicates that the atoms had been electrically charged or ionized by the intense radiation from the neutron star. Although not a direct detection of the neutron star astronomers are calling it a ‘fingerprint’ and it is certainly the best evidence so far.

Proving once again that ‘The Greatest Show on Earth’ is actually not on our planet but in the skies above our heads.