Ever since Galileo first pointed his telescope into the night’s sky astronomers have continued to discover ever stranger and more fascinating objects inhabiting this Universe of ours. Surely among the most mysterious are the objects known as Gamma Ray Bursts (GRBs).

What is a GRB? Well, about once a day, somewhere in the Universe an event occurs that releases as much energy in a few seconds as our Sun will generate in its entire life! This energy is observed as a bright burst of gamma rays. For decades little was known about GRBs and it’s only in the last 22 years that astronomers and astrophysicists feel that they have begun to understand something about these strange entities.

Even the discovery of GRBs was pretty unusual. It is a fact that GRBs are the first, and so far only astronomical discovery to be made by CIA spy satellites. You see it all started in 1963 when the old Soviet Union agreed to the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty that ended the above ground testing of nuclear weapons. The US didn’t quite trust the Russians however; it was thought that the Soviet’s might try to cheat the ban by testing their weapons in outer space. So the CIA launched a series of satellites known as Vela that were designed to detect the sort of gamma radiation that would accompany any nuclear explosion off the Earth.

On July 2 in 1967 the Vela 2 and Vela 3 satellites detected a quick burst of gamma rays but it was soon realized that the burst wasn’t caused by the Russians. Using the data from the two satellites scientists at Los Alamos Nation Laboratory found that the radiation had come from somewhere outside of the solar system. Other bursts were soon detected as well but since the entire Vela program was classified as Top Secret astronomers didn’t get to hear about the discovery until 1973.

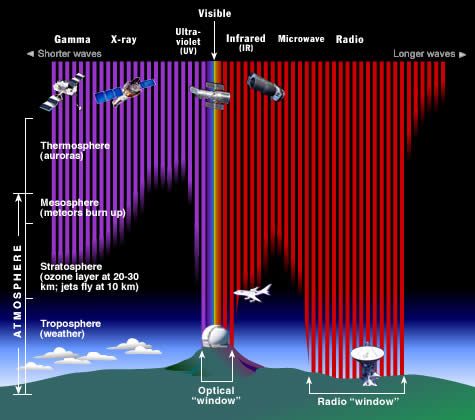

Even after the world’s astronomers knew about the existence of gamma ray bursts progress in understanding them was very slow. Think about it, since gamma rays are blocked by Earth’s atmosphere GRBs can only be detected by specialized satellites. Add to that the fact that GRBs rarely last more than a minute and that they can appear in any part in the sky and you can understand how hard it was to obtain any real data about them.

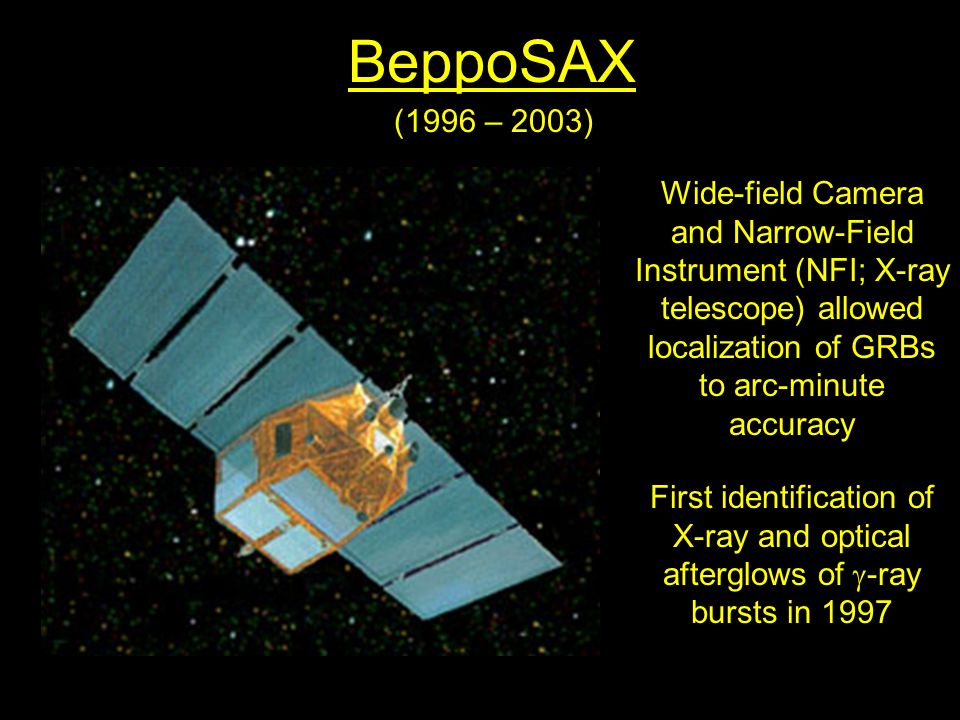

What astronomers wanted to learn most of all was whether or not GRBs had any other electromagnetic component to them. That is, did an optical, radio or perhaps X-ray flash accompany the gamma ray emissions. In order to do this astronomers had to develop a fast reaction network that would quickly communicate the news that a GRB had been detected to astronomers around the world so that other instruments could be brought in action.

Success finally came in February 1997 when the satellite BeppoSax detected GRB 970228 (GRBs are named by the date of their detection YY/MM/DD). Within hours both an X-ray and an optical glow were detected from the same source, a very dim, distant galaxy. Further such detections soon confirmed that GRBs came from such extremely distant galaxies, most of them many billions of light years away. So distant are the locations of GRBs that in order to appear so bright in our sky they must be the most powerful explosions in the entire Universe.

So what are these GRBs? What makes them so energetic? To be honest there’s still a lot to be learned but a consensus of opinion is growing that there are actually two distinct types of GRBs.

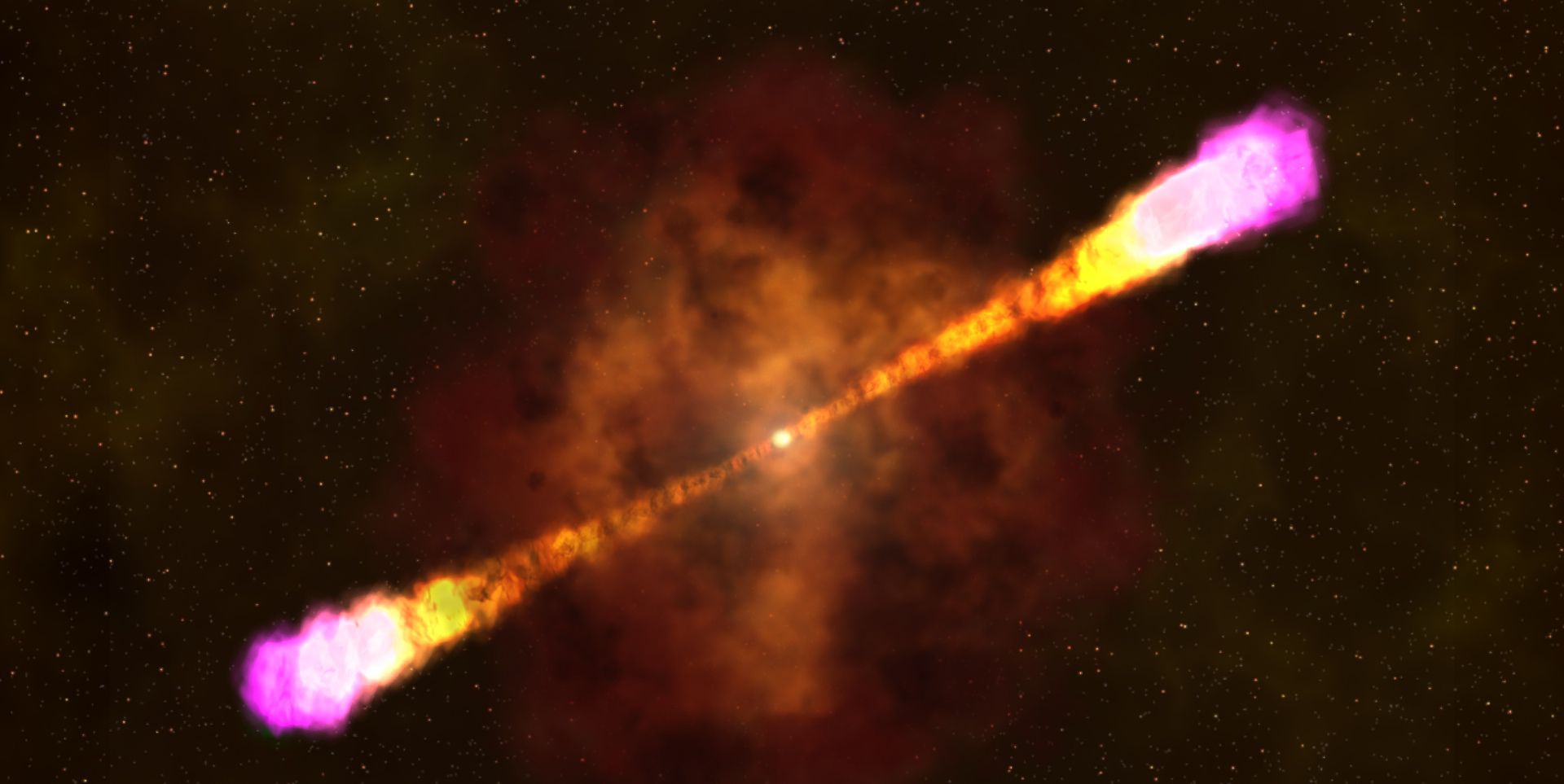

Those that last for a somewhat longer length of time, longer than 30 seconds, are the initial stages of a core collapse supernova. That is the death of a star so massive that it never really settled down like a normal star but instead just implodes after a few million years into a black hole. All of the well-studied GRBs fit this model remarkably well, including their location within galaxies that are undergoing rapid star formation, places where such massive, short-lived stars are far more common.

One interesting feature of this model is that as the star collapses it rotates much more rapidly, just as an ice skater will do when they pull in their arms during a spin. This increase in rotation speed generates a enormous magnetic field at the star’s poles causing the gamma rays that are emitted to squirt out from the poles like the beams of light from a lighthouse. This concentrates the power of the gamma rays into two narrow beams making the GRB look much brighter in the directions those beams travel.

If this lighthouse feature of GRBs is true that implies that we are only seeing a small fraction of all GRBs, only those that are pointing at us. It also means that GRBs are not quite as powerful since their energy is focused into the beams. Again, this model fits the data collected for longer duration GRBs that make up about 70% of those that have been observed.

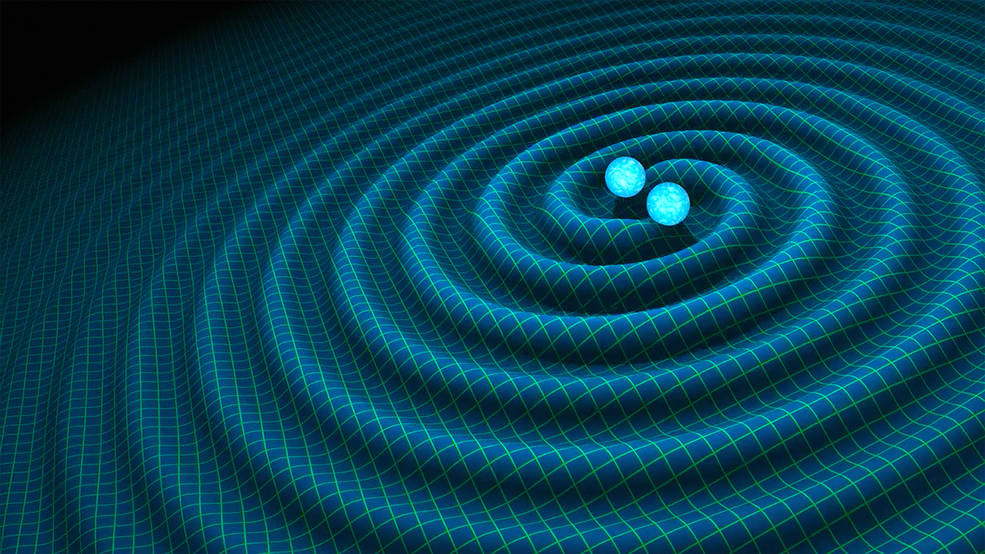

There are also short term GRBs, whose duration averages less than half a second and which make up about 30% of the total observed. Because they are fewer in number and shorter in duration these GRBs are harder to study and therefore less well understood. Several models have been suggested for them but the recent simultaneous observation of a GRB (GRB170817A) only 1.7 seconds after a gravity wave was detected by the LIGO gravity wave observatories implies a direct connection. Based on the nature of the gravity wave observed the event was a merger of two neutron stars. Therefore at least some short period GRBs are the result of neutron stars colliding to form a black hole or a black hole devouring a neutron star.

So, if these GRBs are the most powerful explosions in the entire Universe, could they be any danger to us? Are their any stars in our galactic neighborhood that could collapse and generate a GRB? And what damage would a nearby GRB do?

In fact there are a couple of possible candidates known to astronomers. The stars Eta Carinae and WR 104 are both hugely massive stars that could collapse into black holes sometime in the next million or so years. Of the two WR 104 is closest at a distance of only 8,000 light years.

If WR 104 were to generate a GRB, and if that GRB were aimed at Earth our atmosphere would protect us from the initial burst of gamma and X-rays, only a spike in the Ultra-violet lasting a few minutes would be seen. The long-term effects are much less pleasant however because the gamma and X-rays striking the atmosphere would cause oxygen and nitrogen to combine to form nitrogen oxide and nitrogen dioxide gasses. Both of these gasses are known destroyers of ozone, the form of oxygen in the upper atmosphere that protects us from the Sun’s UV rays. Also the gasses could combine with water vapour in the air to form droplets of nitric acid that would rain down causing further damage.

Of course all of that is just speculation, we really have no idea what would happen here if a GRB from a star as close as WR 104 should strike the Earth. Before you start to panic however remember that GRBs are very rare, only one per day in the entire Universe. Let’s be honest, we’re a far greater danger to ourselves than Gamma Ray Bursts are!