The main pursuit of paleontology is to learn the pathways by which Earth’s first creatures evolved into the species we see today, to study evolution in the field. In this month’s post I’ll be discussing stories that illustrate evolution from both the beginnings of multi-cellular life to observations of evolution in action today.

For most of life’s time here on Earth it consisted of nothing but single celled organisms. Then, about 600 million years ago the first simple multi-celled creatures came into being, creatures that have become known as the Ediacaran fauna. Because these first plants and animals had nothing in the way of hard parts however fossils of them are exceptionally rare and don’t reveal much about their anatomy.

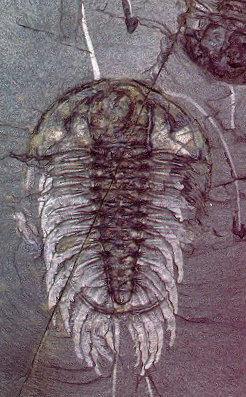

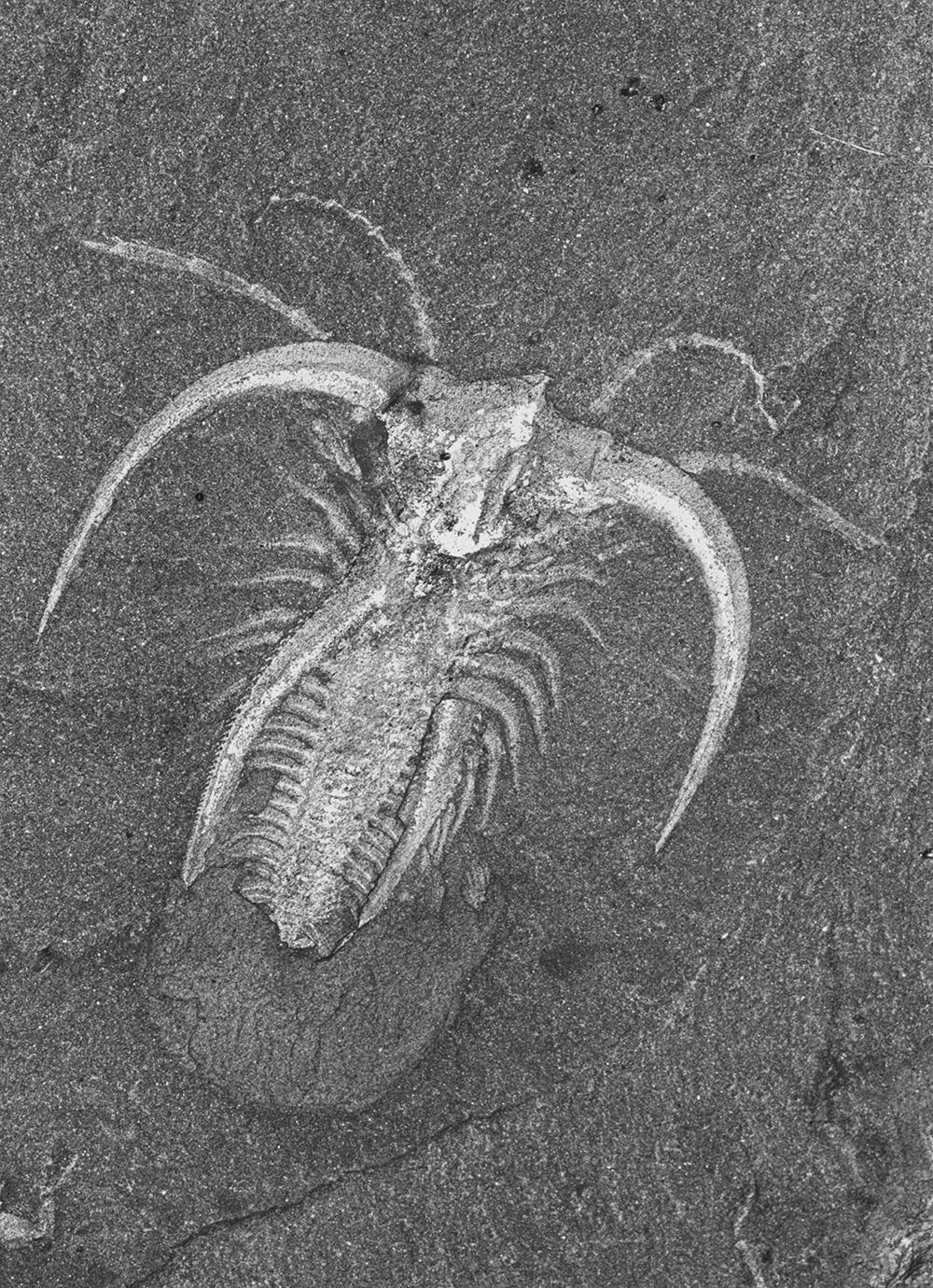

Animals with hard parts first appeared about 550 million years ago during the early Cambrian period and some of the best fossils from the Cambrian period are found in British Columbia in the world famous Burgess Shale and nearby fossil sites. The remarkable preservation of the fossils from the Burgess Shale is due to both the fine grained particles making up the shale as well as the fact that the animals that were fossilized seemed to have been buried intact in mudslides before their remains could be eaten by scavengers.

As might be expected the creatures found in the Burgess Shale were mainly small, the size of a finger being rather common. After all multi-cellular life was brand new and it takes a while to go from being microscopic to the size of a human being let alone that of a whale.

Size has its advantages however, particularly if you want to catch and eat other creatures. So it’s no surprise that the biggest animal yet discovered in the Burgess Shale, a creature known as Anomalocaris, was a predator about one meter in length. Despite its strangeness, the size of Anomalocaris made it the Tyrannosaurus rex of its day.

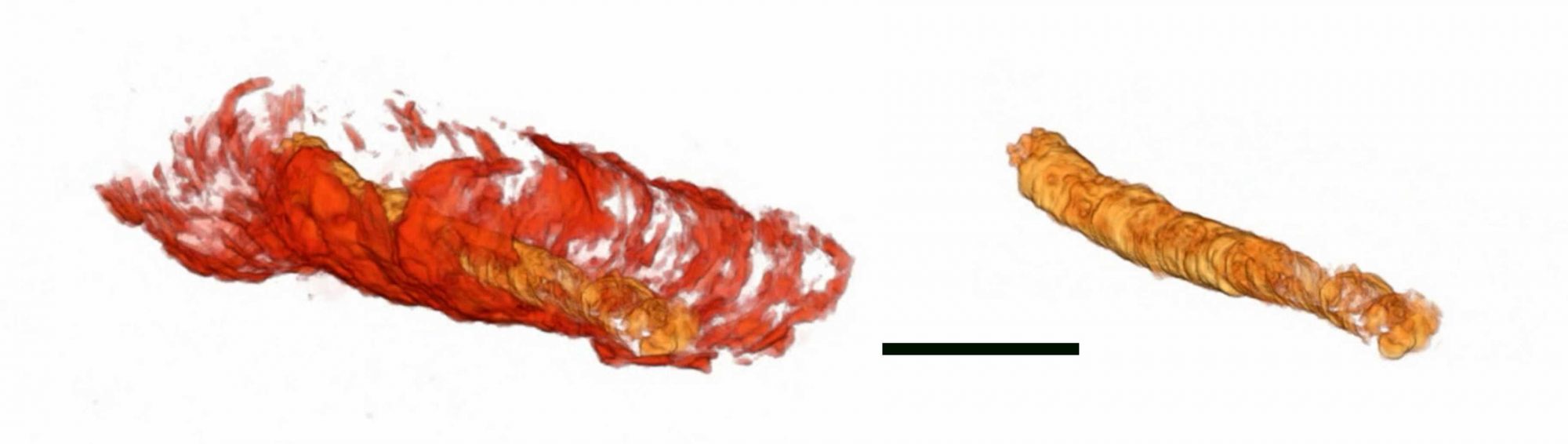

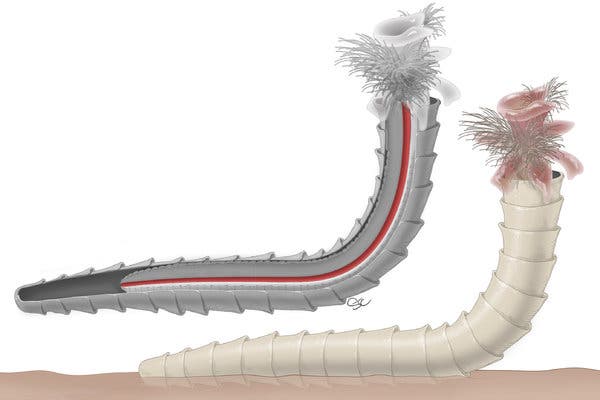

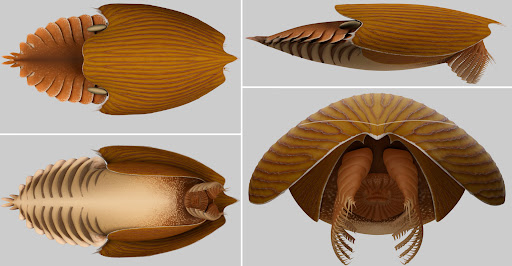

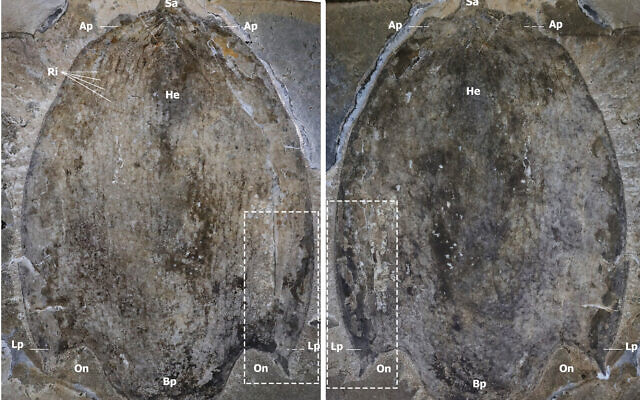

Now another large and equally strange creature has been discovered by paleontologists associated with the Royal Ontario Museum in an outcrop of shale near the Burgess Shale site in British Columbia and of the same age. Given the name Titanokorys gainesi the fossil belongs to a group of arthropods characterized by having a large, three part carapace covering most of their bodies that made them look almost like living heads.

T gainesi in particular had a broad, flat carapace about a half-meter in length along with multifaceted eyes and two spiny claws to grab food and bring it to a mouth shaped like a slice of pineapple. The paleontologists who described T gainesi speculate that the creature may have used its large carapace like a plow to stir up the muddy ocean bottom so that its claws could capture worms and other small animals.

T gainesi is yet another example of how, half a billion years ago evolution was experimenting to find solutions to the problems of how to survive in a hostile world. That same problem is still being faced by the life forms of today’s world but modern animals have the additional difficulty of having to adapt to a rapidly warming planet due to human induced climate change. In order to survive in this new environment Earth’s creatures must do what they have always done, adapt and evolve.

Now a new study by ornithologist Sara Ryding of Deakin University in Australia has described some of the changes that are already taking place in warm-blooded animals. Published in the journal ‘Trends in Ecology and Evolution’ the research details the anatomical changes, ‘shapeshifting’ that have been measured in a large number of bird and mammalian species.

For example several species of Australian parrot have been found to be growing beaks that are 10% larger when compared to preserved specimens from 100 years ago. The same increase in beak size has also been found in North American dark-eyed juncos, a variety of songbird. In both cases the increase in bill size correlates positively with a measured increase in average temperature in the areas populated by the birds.

In mammals such as wood mice and masked shrews a similar 10% increase has been measured in tail length and leg size. All of these adaptations have one thing in common, they provide the animal with a larger surface area to radiate heat and cool their body temperature. Again there is a clear connection for the larger body parts to rising temperatures in the animal’s habitat.

The fact that some species are evolving in response to global warming shouldn’t be taking as a sign that those animals are solving the problem of climate change however. As Doctor Ryding puts it, “shapeshifting does not mean that animals are coping with climate change and that all is ‘fine’. It just means that they are evolving to survive it. But we’re not sure what the other ecological consequences are, or indeed that all species are capable of changing and surviving.”

Paleontologists have recognized at least six separate ‘mass extinctions’ in the fossil record. Some of these extinctions appear to have been caused by asteroid or comets impacting the Earth while others may have been due to massive volcanic eruptions. Right now our planet is experiencing another extinction event and there’s little doubt as to its cause, human beings!