Living creatures exhibit a wide variety of lifestyles, some of which to us can seem bewilderingly strange. Take the common pantry moth, also known as the Indian meal moth, biological name Plodia interpunctella. A frequent household pest P interpunctella lays its eggs in packages of flour, cereals and other dry goods. The caterpillar stage of the moth then lives by consuming some of the food in which it was born.

Normally a peaceful vegetarian when left alone, if two caterpillars of P interpunctella happen to come upon each other it can be a fight to the death with the victor literally eating its vanquished foe. And it doesn’t matter even if the two combatants are siblings the instinct to eliminate the competition, and acquire a little protein, just takes over.

Such violent behavior is instinctive, adapted for a normally solitary lifestyle. It can be asked therefore, under what conditions and how long a time would be required to change those instincts? Well, a team of biologists at Rice University in Texas and the University of California at Berkeley wondered about that and set up an experiment to answer those questions. Pantry moths caterpillars it turns out make good lab animals because they’re used to living in containers, their food is cheap and their lifespans are so short you can get a lot of generations in just a few years.

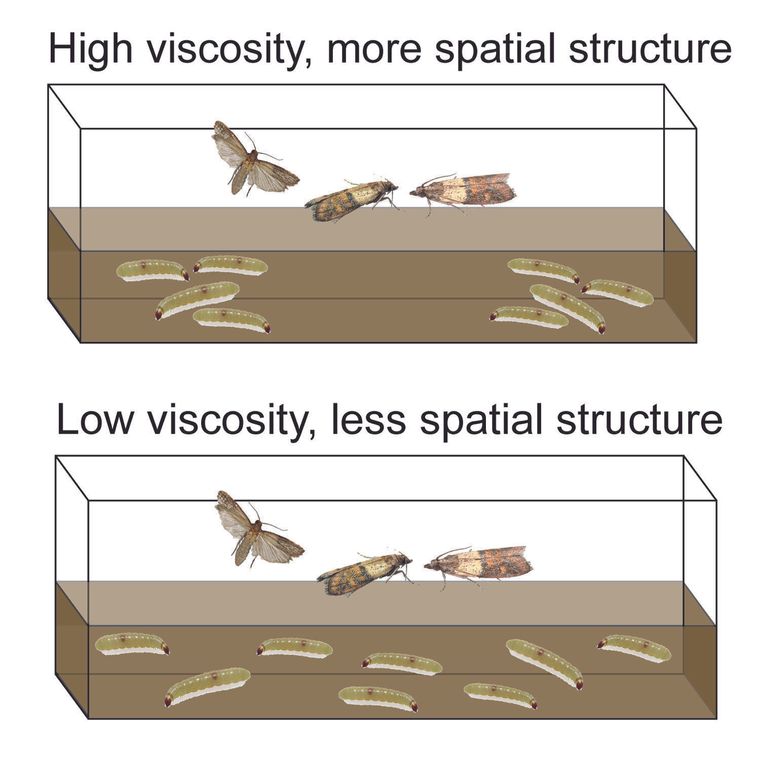

In their experimental setup the researchers wanted to control the dispersion, that is the spatial spread that a brood of caterpillars could attain. They did this by establishing five separate habitats and varying the viscosity of the food in each. The less viscous the food the greater the caterpillars could spread out, the more viscous the food the more often a caterpillar would encounter a sibling.

What the biologists discovered was that over ten generations those caterpillars that were forced to remain in close quarters with their relatives showed a marked decrease in cannibalistic behaviour. According to Volker Rudolf of Rice University and one of the study’s authors. “Families that were highly cannibalistic just didn’t do well in that system. Families that were less cannibalistic had much less mortality and produced more offspring.”

This result provides strong evidence for a theory advanced by Rudolf and co-author Mike Boots of UC Berkeley. Their idea is that when animals, not just pantry moths, interact with each other more the degree of cannibalism declines because the odds of eating your own sibling, who shares half of your genes, increases.

Whether these results can be applied to other species remains to be seen. Also it is worth noting that in the experiment the supply of food was not constrained, everybody had plenty of food to eat. In a situation where resources are severely limited eating a sibling might be the only way for anyone to survive!

However there is a growing amount of evidence that the instinct towards violence can be altered, and over the course of not too many generations. In my post of 11 December 2019 I discussed the work of Doctor Belyayev, a Soviet biologist who conducted selective breeding experiments with foxes. By breeding together those animals that appeared tamer Doctor Belyayev succeeded in only six generations in producing a strain of fox that was as tame as a domestic dog. At the same time Dr. Belyayev mated those foxes that seemed especially violent and again in only six generations produced a strain that was pathologically vicious.

And in my post of 17 June 2020 I reviewed the book ‘The Better Angels of our Nature’ by Harvard Professor of Psychology Steven Pinker. That book considered in great detail the mounting evidence that living in a civilized society is actually making human beings less violent. In a sense all three of these sources point towards the same general theory, that under the correct conditions violent behavior can be greatly reduced if not eliminated from a population within an evolutionarily short period of time.

Of course there is still much more that needs to be learned. But it is becoming clear that we can learn how to control our violent animal behavior, if we can only find the will to do so.