With the Covid-19 virus spreading around the world it’s critical that we study the lessons learned from past pandemics if we are to have any hope of minimizing the loss of life than now threatens our society. Since this is as much history as medical science I decided that for this post I would ask my brother Tom, a history teacher at Mastbaum High School here in Philadelphia for his help in telling the story of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918.

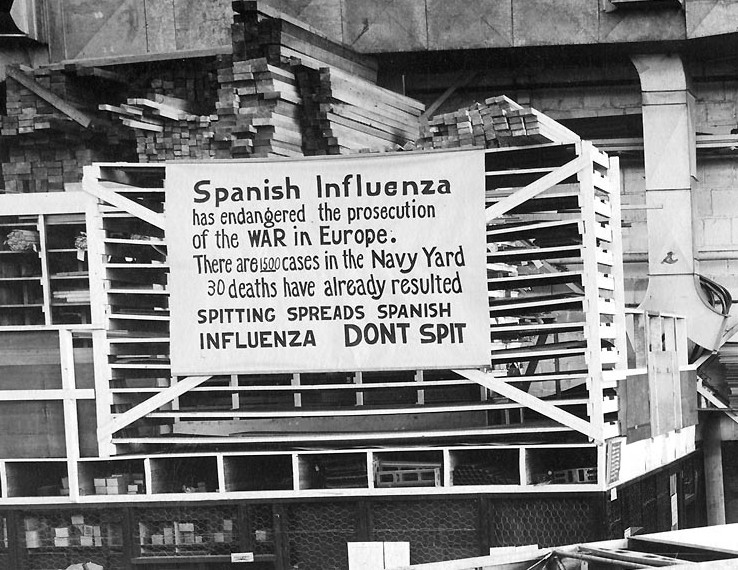

At the beginning of the year 1918 the world was fully engulfed in the First World War. After three years of conflict the continent of Europe had become nothing more than a single large battlefield. Then, in January of that year a new player entered the war, Influenza. Ironically, the influenza pandemic of 1918 has since become known historically as the Spanish flu because, since Spain was a neutral in the World War, they were the only country that would honestly report the large numbers of the sick and dead that were caused by the disease.

To this day scientists are still not precisely certain where the outbreak started. There is evidence that it may have started at a field hospital outside the French lines. Or it could have begun in an US Army training camp in Kansas. No matter where it began by the end of the pandemic an estimated 17 to 50 million people had died worldwide. Now influenza is of course the flu, a disease that we are all familiar with. This particular strain of the flu however was a flu like no other however as it struck down the strong and youthful as well as the old and the very young who are the usual victims of the flu.

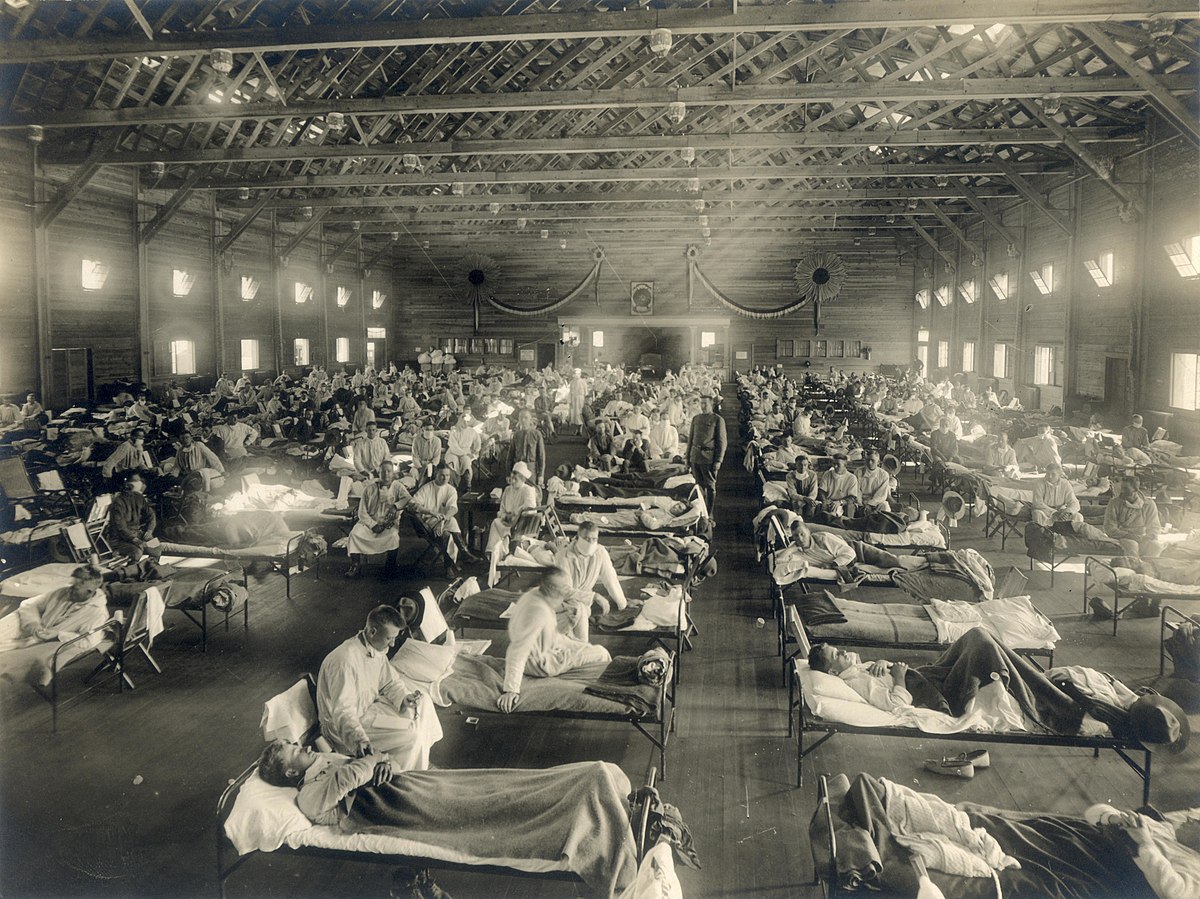

The French field hospital that is considered by many to be the original source of the disease was overcrowded and plagued by sanitation problems. Food for the hospital’s patients came from livestock that were kept behind the hospital, much too close to the large number sick and injured soldiers. Many scientists are of the opinion that the disease began in a flock of chickens that were being kept for food behind the hospital. The bird’s droppings passed the infection to some pigs that were also being kept as food before leaping into human hosts.

Those soldiers who recovered at the field hospital then carried the flu with them back to the trenches when they returned to their units, passing the illness on to their comrades. Before long a few of the sick French soldiers were captured by the Germans, in the process passing the disease on to them. Soldiers on both sides who were given leave then took the infection back to the cities and towns of their countries spreading the disease ever further.

In the United States the first recognized case of the flu was Albert Gitchell, an Army cook at Ft. Riley, Kansas. As a cook Gitchell’s job was to feed the recruits and as he did so he unknowingly passed the disease on to hundreds. Those recruits who completed their training were shipped to Queens New York to wait for a ship to transport them to the battlefields in France. City officials in New York were slow to recognize the danger of so many sick soldiers in their midst and soon the infection was spreading throughout the city and on to the other cities of America.

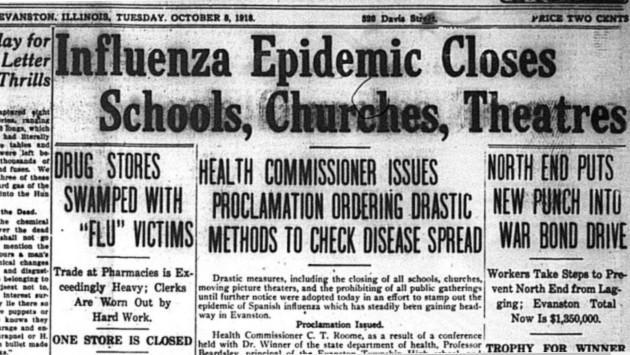

In fact politicians and civil servants throughout the world were slow to react to the pandemic. Partly this was due to their preoccupation with the requirements of conducting the war, especially the need for secrecy. In addition however governments throughout history just never seem to be able to recognize the dangers of a health or environmental crisis until they have grown into a huge disaster.

The politicians in 1918 treated this new flu as if it were hardly different from the flu of other years. They considered it to be no more than a temporary nuisance and felt little urgency in either treating the victims or stopping the spread of the disease. More than anything else governments are concerned about a panic starting amongst their people so they always tend to try to hide really bad news.

Eventually however the growing number of the sick and dead became so large that even the politicians had to take action. In many cities activities that involved large crowds were limited in size or even called off. For a short time church services were held in the outdoors in an attempt to reduce the spread of the virus but it wasn’t long before such gatherings were being cancelled entirely. As the crisis worsened Police began to wear surgical masks in an effort to protect themselves, schools were closed and cities like New York and Boston began to resemble ghost towns as people remained in their homes.

Philadelphia was one city that seemed to have escaped the worse of the epidemic. In the early part of September 1918 there had been a small number of cases of the flu at local hospitals but few deaths.

As a part of the Victory Loan Program to benefit the war effort the city fathers of Philadelphia were planning what they knew would be the biggest parade in the city’s history. The city’s health commissioner had been advised by the health commissioners of New York and Washington to cancel the parade but he owed his job to the local party bosses and so under pressure from the politicians he allowed the parade to go on as scheduled on the 28th of September 1918.

On that day the citizens of Philadelphia lined Broad Street in the thousands, creating an enormous crowd that pressed against each other, the perfect breeding ground for any infectious disease. Within days the flu had spread throughout the city and the death rate soon rose beyond that other the those of Boston or New York.

In contrast the city officials in St. Louis listened to the warnings of their health officials and cancelled their Victory Bond parade. Thanks to the wisdom of their leaders the city of St. Louis escaped the worst of the plague. The chart below dramatically illustrates the consequences of each city’s leaders response to the threat posed by the flu.

The influenza pandemic of 1918 affected every corner of the world and remained a deadly problem until it finally died out around December of 1920. The precise death toll caused by the Spanish Flu will never be known for certain but many scientists believe that it was greater than the number of those who perished in the actual war. In many cities throughout the world the dead were so numerous that they were buried in mass graves.

In the hundred years since 1918 the United States has not witnessed a health emergency anywhere near the scale of the Spanish flu, until now. If we are to fight the Covid-19 pandemic then we are going to have to learn the lessons of the past, a task that so far we are not accomplishing very well. The policies of our governments must be solidly based on medical science, not on hunches or wishful thinking. We must demand that our leaders act with the sole goal of saving as many lives as possible, ignoring all considerations of winning elections or protecting the economy. Covid-19 is going to be a test of not only of how much we’ve learned about fighting infectious diseases, but also about whether or not we have the wisdom to act on the lessons we’ve learned.