There have been quite a few dino discoveries the past few weeks. I have four stories to cover so let’s get to it.

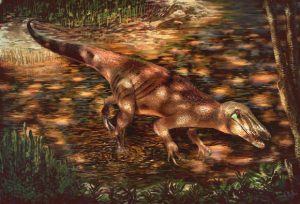

I’ll start with the discovery of a new species of ‘horned dinosaur’ formally known as a Ceratopsian and related to the well-known Triceratops. The new species, see image below, is named Crittendenceratops krzyzanowskii and is based on the re-evaluation of bones that were discovered almost 20 years ago in 73 million year old rocks southeast of Tucson Arizona. A team of researchers from the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science (NMMNH) carried out the re-examination finding “morphological features right away in the material of Crittendenceratops to establish a new species,” according to Sebastian Dalman the team leader.

According to the researchers, C krzyzanowskii was approximately 3-4 meters in length and likely weighted 700-800 kilos. The 73 million year age of Crittendenceratops puts it very close to the end Cretaceous period, making it probably one of the last species of ‘horned dinosaur’ to walk the Earth.

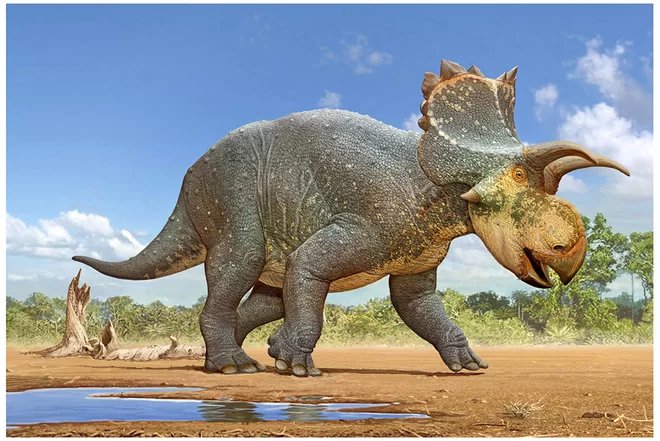

One of the big debates going on presently in the paleontological community concerns exactly when it was that the first feathers developed and how many different types of animals had them. Not too many years ago the very idea of a dinosaur having feathers would have been shocking. Now however it is well established that some dinosaurs worn feathers as insulation to help keep them warm. Perhaps even the mighty T rex himself was covered with a warm layer of fuzzy feathers.

Now an analysis of two fossils may push the origins of feathers back another 70 millions years and spread their occurrence to another entire group of extinct reptiles. A team of paleontologists from Nanjing University in China have found what they believe to be short, fuzzy, thread like structures on specimens of pterosaurs, the bat like flying reptiles that lived at the same time as the dinosaurs, but which were not dinosaurs. The fact that many of these thread like structures, see image below, split at their ends in a fashion similar to the development of feathers leads the researchers, lead by Professor Baoyu Jiang, to conclude that they are in fact the earliest fossil evidence of feathers.

The spread of feathers 70 million years further backward in time and to another entire group of extinct reptiles not only illustrates how wondrous the past history of life truly is, but also how piece by piece we are slowly uncovering it.

The very first dinosaur specimens to be scientifically described came from the United Kingdom. In fact the very word Dinosaur (Terrible Lizard) was coined by the British naturalist Sir Richard Owen. The paleontology of the UK has been studied for so long, and so thoroughly that you might think that there couldn’t be much left to discover. Erosion can often be a paleontologist’s friend however, revealing treasures that were hidden beneath layers of uninteresting rock.

This is what has happened in the Ashdown Formation in the English county of East Sussex. In the sandstone cliffs along the shore 85 dinosaur footprints have been recently discovered. Not only that but the prints are from as many as 13 different species, giving scientists a glimpse into what the quiet English countryside was like 100-140 million years ago. See image of a print below.

The prints include many from well known dinosaurs, the Iguanodon, the Ankylosaurus, a possible Stegosaur as well as several Sauropods and Theropods (Basically that’s all of the dinosaurs you learned about when you were a kid!). Some of the prints are so well preserved that the texture of the animals skin can easily be seen, and therefore studied. See image below. Finds like these give paleontologists a wealth of information about the ecology of the ancient world, showing us how different, and yet how similar the world was so long ago.

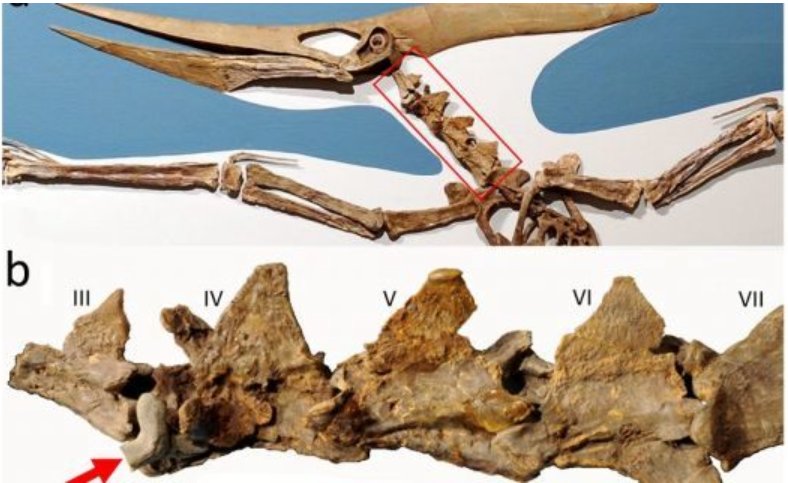

My final story today may not be the most important scientifically but it is almost certainly the most spectacular. At least it has the coolest picture, see image below.

Researchers at the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum have been cleaning and preparing a well-preserved skeleton of a Pteranodon, a large species of those flying reptiles I mentioned above. As the researchers were cleaning the area of the fossil’s neck they noticed something stuck in between two vertebra, a shark’s tooth! See image below.

Now the researchers do not believe that the shark, the tooth identifies it as a species known as Cretoxyrhina mantelli, leapt out of the water in order to attack the Pteranodon in mid flight. Rather they speculate that the flying reptile was floating on the surface of the ocean when the shark ambushed it from below. Even today sharks are known to attack seabirds in this manner, I’ve actually witnessed such an attack myself. So have sharks been feeding for millions of years off of flying animals who are foolish enough think that the ocean is a nice, quiet place to rest for a few minutes? By the way, this fossil Pteranodon was actually discovered back in the 1960s. Another example of how a re-examination can make new finds.

The fossils found by the researchers in California give us a small window into a past event that is both dramatic and fascinating. With each such window we gain a better picture of the history of life on Earth.