The BepiColombo robotic probe to Mercury is in many ways the most complex space mission yet attempted. For one thing it is actually three spacecraft in one. Two Mercury orbiters, the Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) designed and built by the European Space Agency (ESA) along with the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO) constructed by the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). These two scientific missions are stacked together on top of a propulsion module called the Mercury Transfer Module (MTM). Simply organizing a mission combining two probes from two space agencies had to be a challenge.

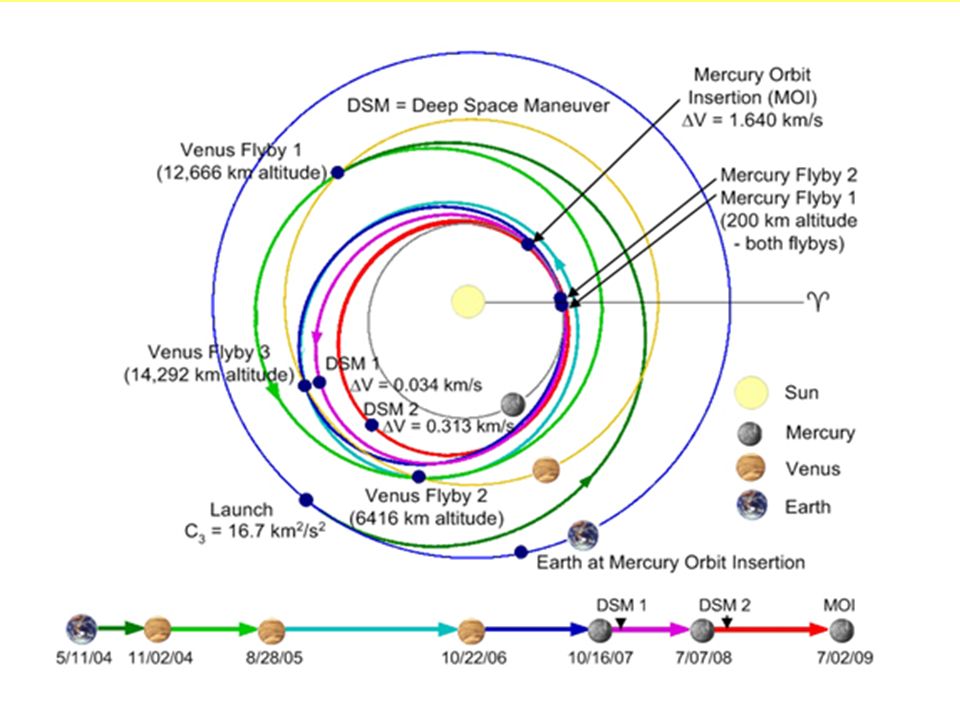

Still, that was child’s play when compared to the task of getting BepiColombo to Mercury. Launched on 20 October 2018 the spacecraft will not enter orbit around Mercury until 5 December 2025. During that long voyage BepiColombo will flyby and receive gravity assists from Earth once, Venus twice and Mercury itself six times. The difficulty of getting to the Sun’s closest planet is the big reason why there have been more unmanned missions to distant Saturn, two Voyagers plus Cassini, than to comparatively nearby Mercury, one Mariner along with the Messenger mission.

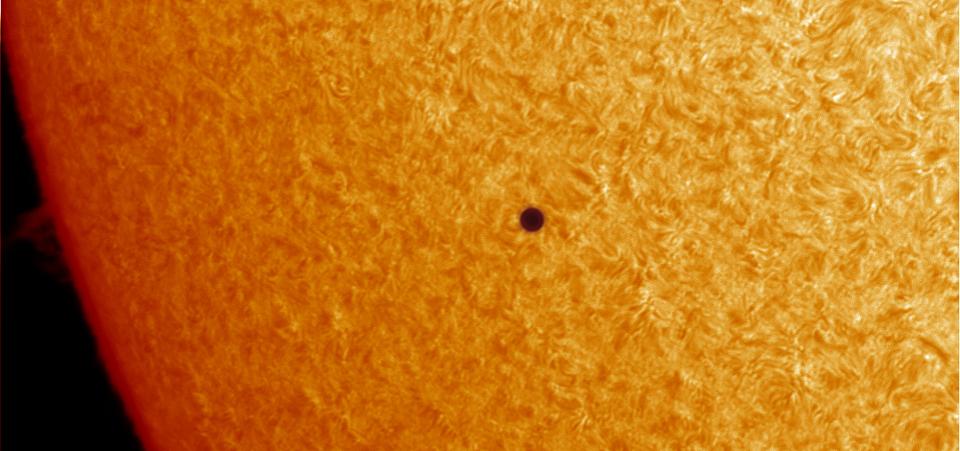

That true, although Mercury is actually only about 20% further away from Earth than Mars is, 90 million kilometers versus 75 million. On the other hand Saturn is fully 17 times further from Earth than Mars is. So why have we sent more spacecraft to Saturn than Mercury?

Speed is one big reason. Orbiting so close to the immense gravity of the Sun Mercury has to possess a very high orbital velocity. In fact if you consider the difference in their orbital velocities, delta vee as astronauts put it, Mercury is only a little ‘closer’ to Earth, 18 km/sec, than Saturn is, 20km/sec. And when you’re sending an unmanned robotic probe to an extraterrestrial body the length of time the journey takes doesn’t matter, which makes speed matter more than distance since that requires more fuel.

Another reason that sending a spacecraft to Mercury is difficult is that the nearby Sun’s gravity is so strong, while Mercury’s is rather weak. This makes finding a stable orbit around Mercury rather difficult, especially an orbit that allows you to investigate all of the areas on the planet you want to observe.

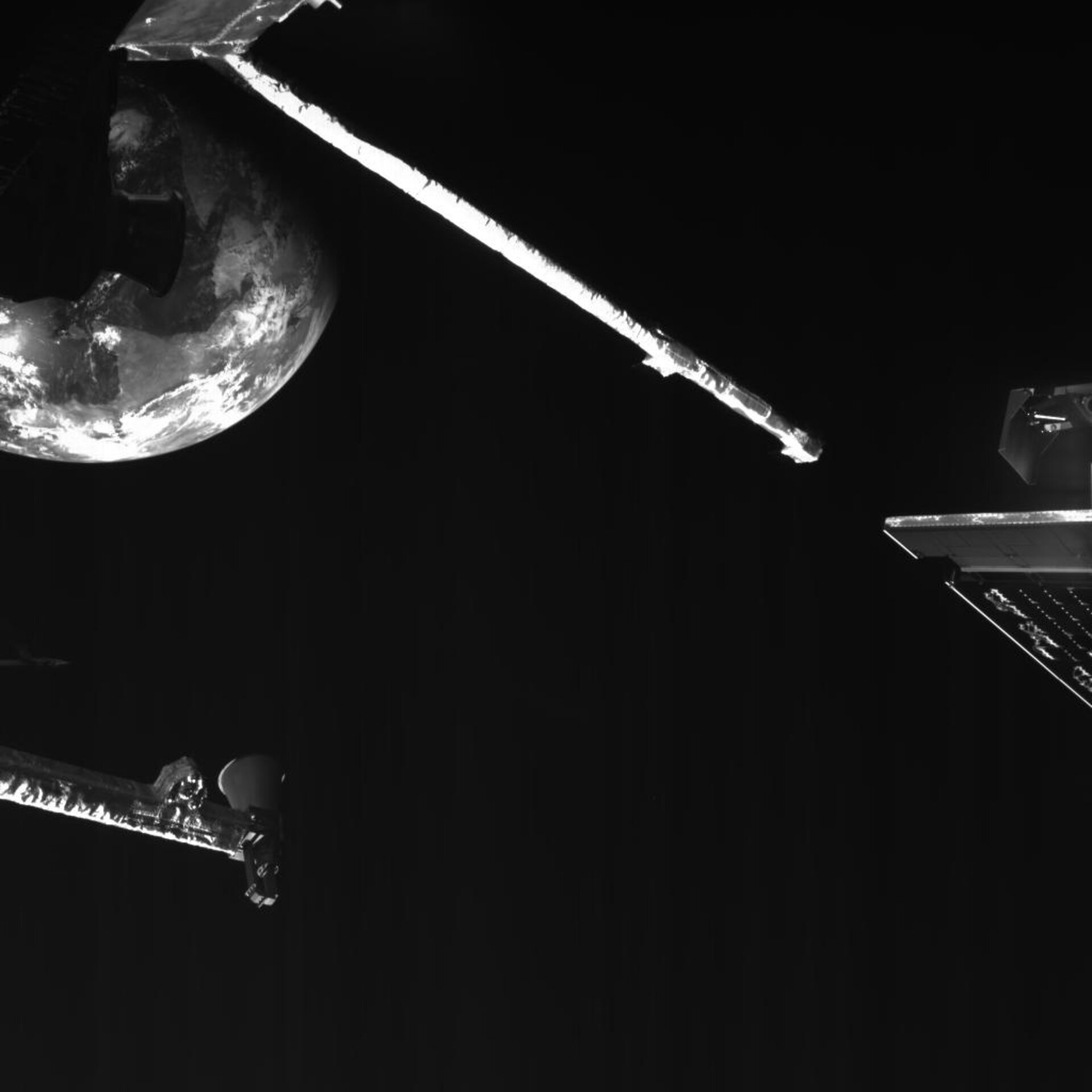

BepiColombo has just completed the first if it’s flybys, saying a last Goodbye to Earth on the 11th of April, see image below. Later this year in October the probe will make the first of two consecutive flybys of Venus. Hey you known, Venus is big and bright in the evening sky right now so if you go outside on a clear night not long after sundown, BepiColombo will be somewhere between you and that big, bright evening star to the west.

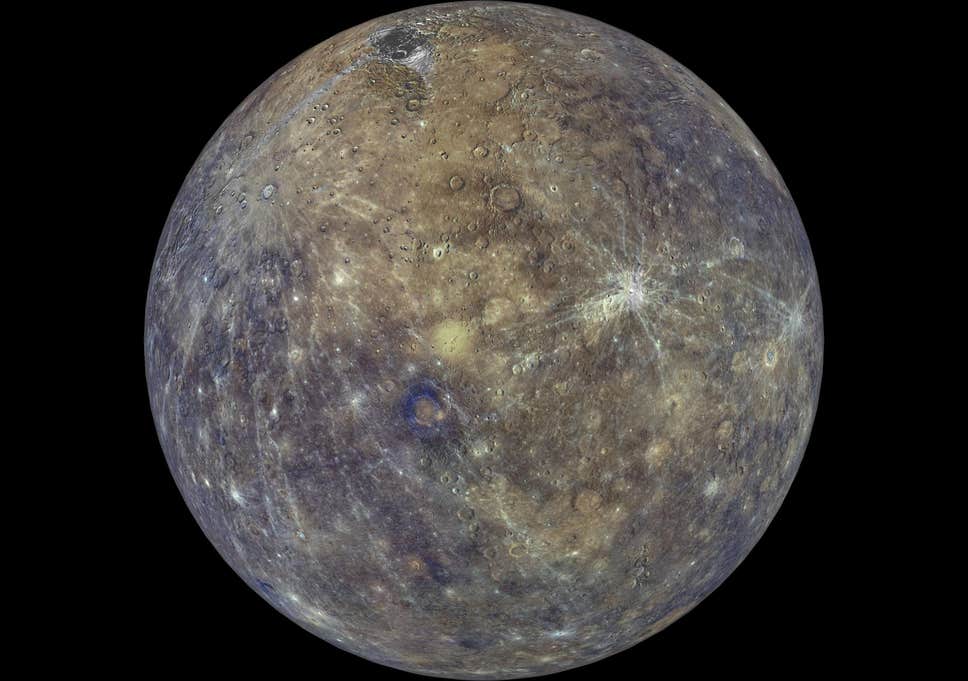

Once the combined spacecraft finally settles into Mercury orbit the two orbiters / instrument packages will separate and begin their studies of Mercury. The ESA’s MPO orbiter is outfitted with an array of cameras and spectrometers along with a radiometer, a laser altimeter magnetometer and accelerometer for the study of Mercury’s composition as well as compiling a more accurate map of the planet’s surface.

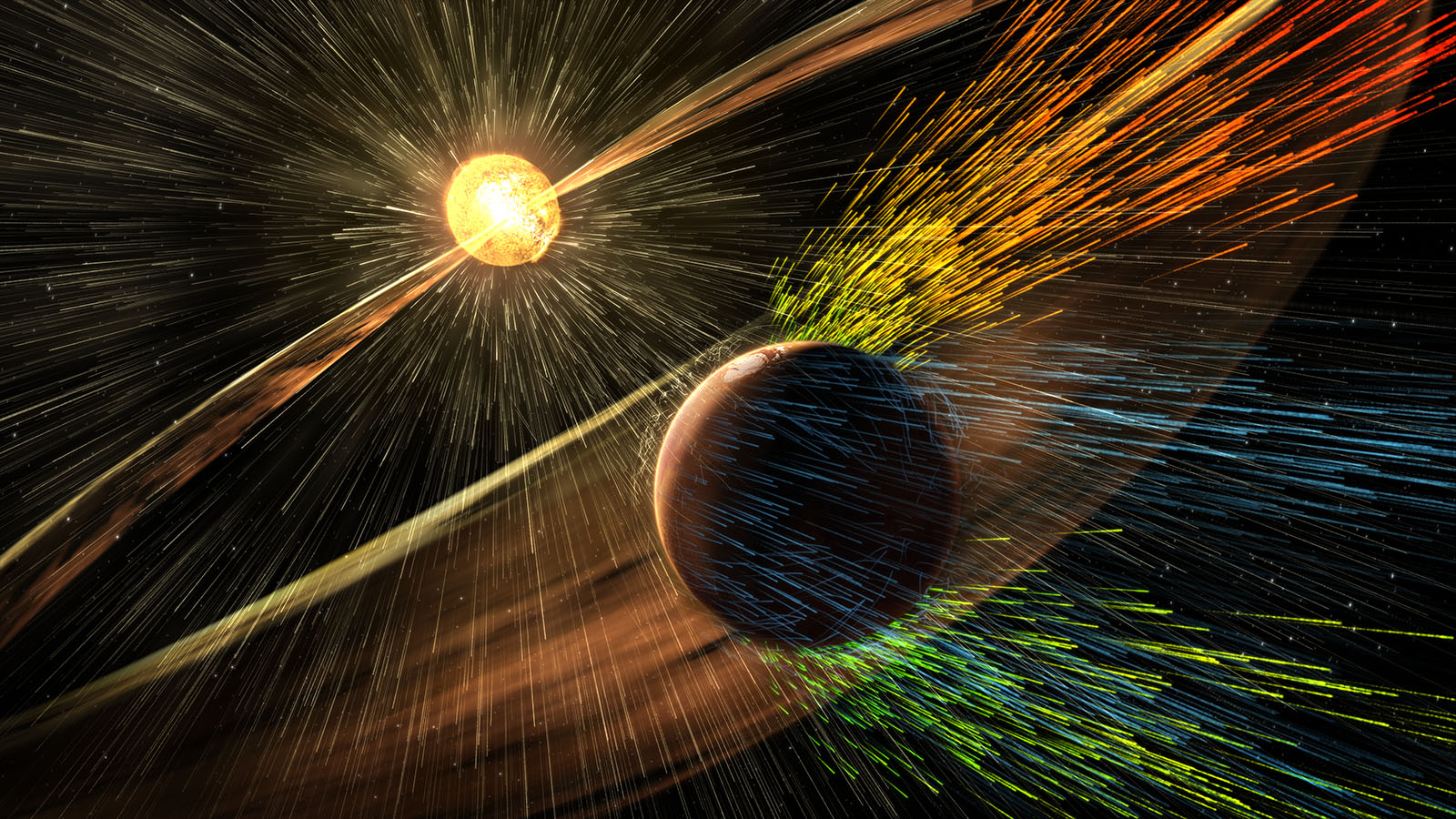

Japan’s MMO probe on the other hand carries instruments designed to study Mercury’s extremely thin atmosphere, the planet’s magnetic field and the way in which they both interact with the power of the Solar wind blowing past the planet. The results of these observations could be especially interesting since they will tell us a great deal about how the evolution of both Mercury and nearby Venus were influenced by the power of the Sun.

The proposed time frame for the scientific portion of BepiColombo’s mission is for one year after orbital insertion but with the possibility of an additional one-year extension for both orbiters. It’s possible that the success of BepiColombo will not only provide much valuable data about the Sun’s closest planet, but an example of how the space agencies of different nations can work together.

If only the politicians of different nations followed that example.