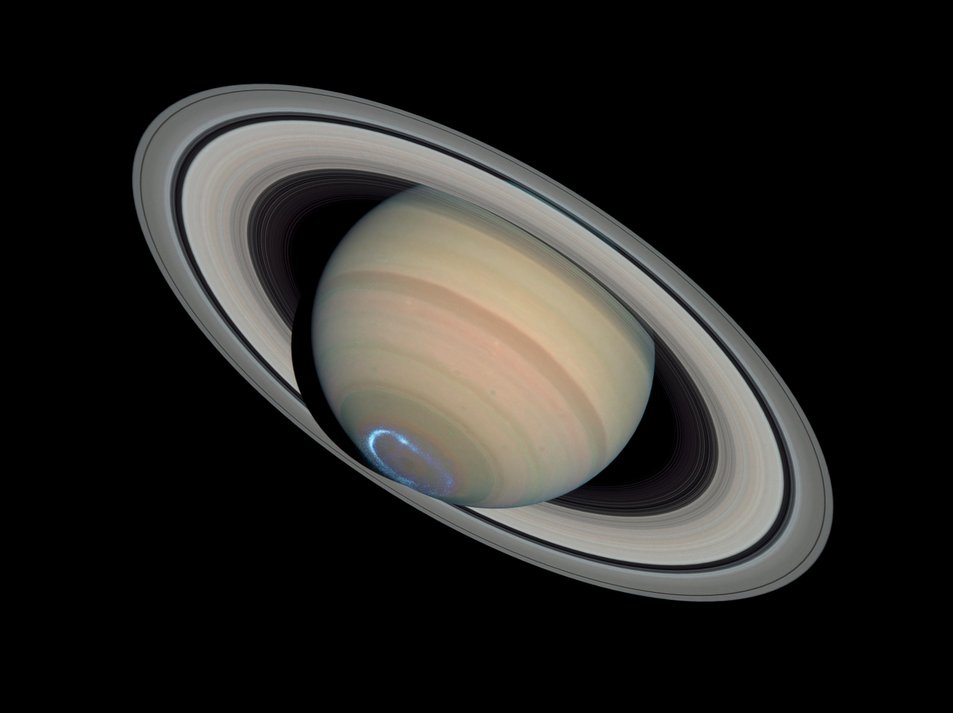

Nowadays we’re all used to seeing beautiful images of astronomical objects, whether from Hubble or now James Webb or from some other observatory. To my mind however, nothing beats seeing the planet Saturn with your own eyes through even a small telescope. Somehow looking through a telescope is different; maybe it’s the movement of the air causing a little shimmer that makes it seem different from an image.

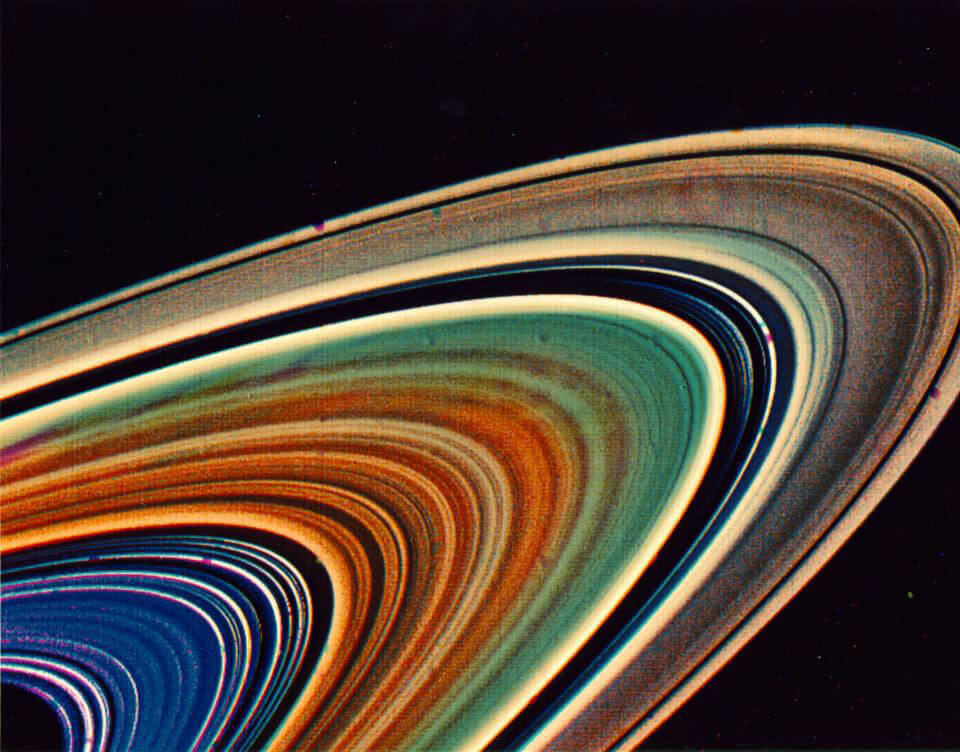

Of course it’s the rings that make Saturn the most beautiful planet to see. They just seem so unreal, fairy like in a sense. And in a telescope they seem to be as solid as the planet they circle, even though in your mind you know that they are actually made up of trillions, hey millions of trillions of small snowballs. Each snowball a separate moon with its own orbit around Saturn.

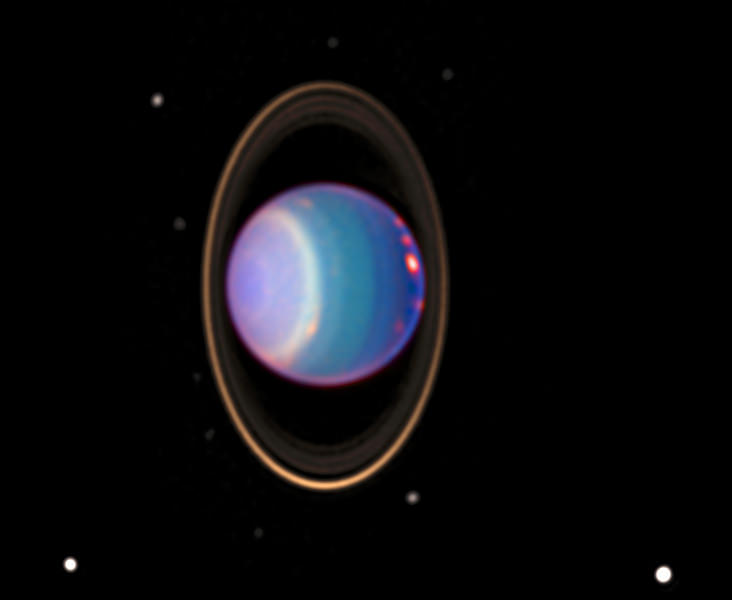

Back before the space age it was thought that only Saturn had rings, you couldn’t see any around any other planet using the telescopes of the 1950s or earlier. Some astronomers claimed to see faint rings around Uranus but it wasn’t until 1977 that observations by James Elliot, Jessica Mink and Edward Dunham convinced the astronomical community that Uranus did indeed have rings. Then in 1979 as the Voyager 1 space probe was flying by Jupiter a couple of its images of the giant planet showed a faint ring system, a discovery that Voyager 2 would confirm a few months later. Finally in 1989 Voyager 2 found that the last of the solar systems gas giants, Neptune also had a set of rings. Since all of the solar systems giant planets are now known to have rings astronomers have begun to wonder if there is some connection, do all gas planets, even those in other solar systems, have rings.

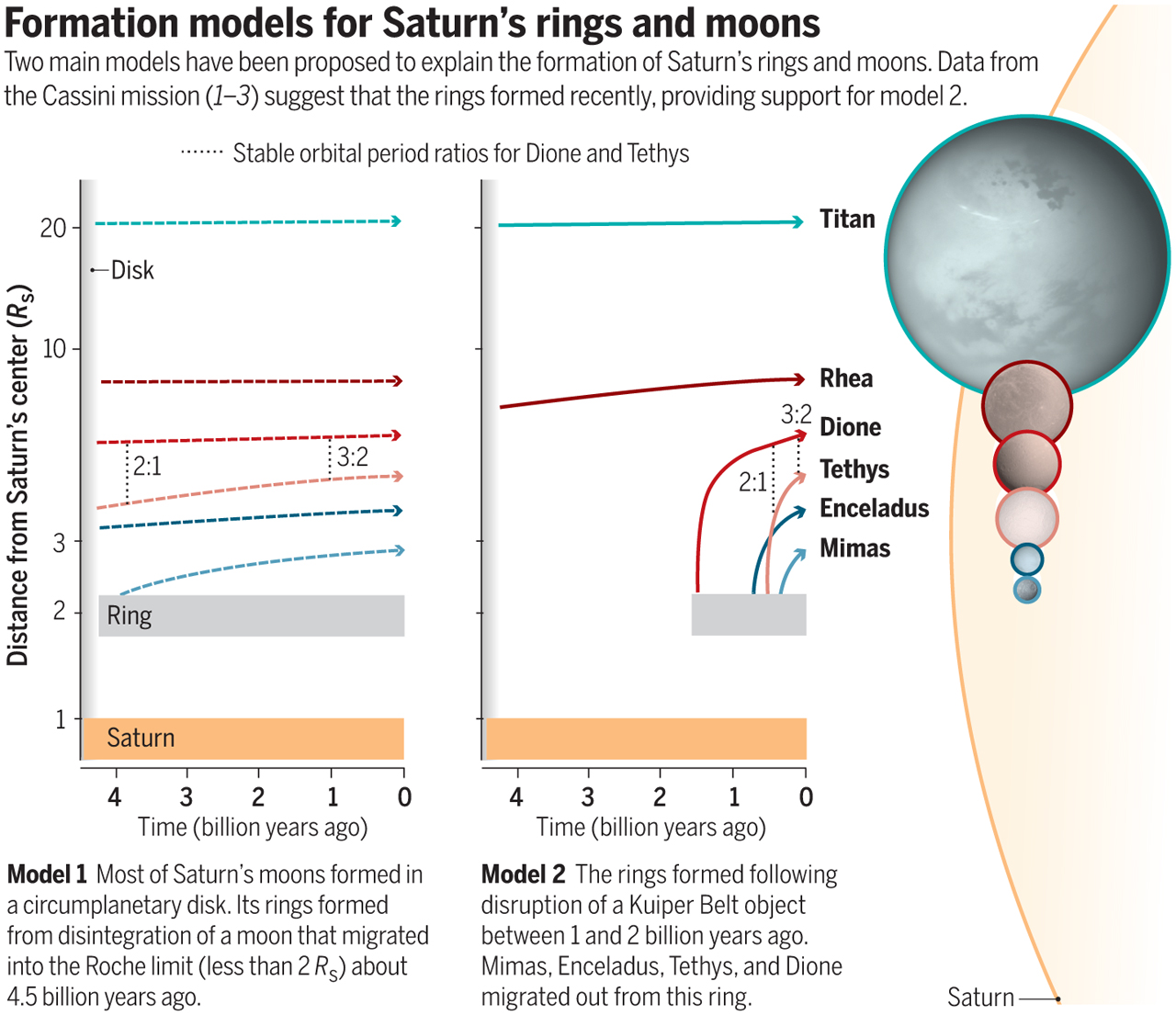

Which of course begs the questions, why do any planets have rings? How do rings form, and how long do they last. Since we’ve never actually seen a ring system forming we really only have theories and educated guesses and astronomers have argued for decades over the details.

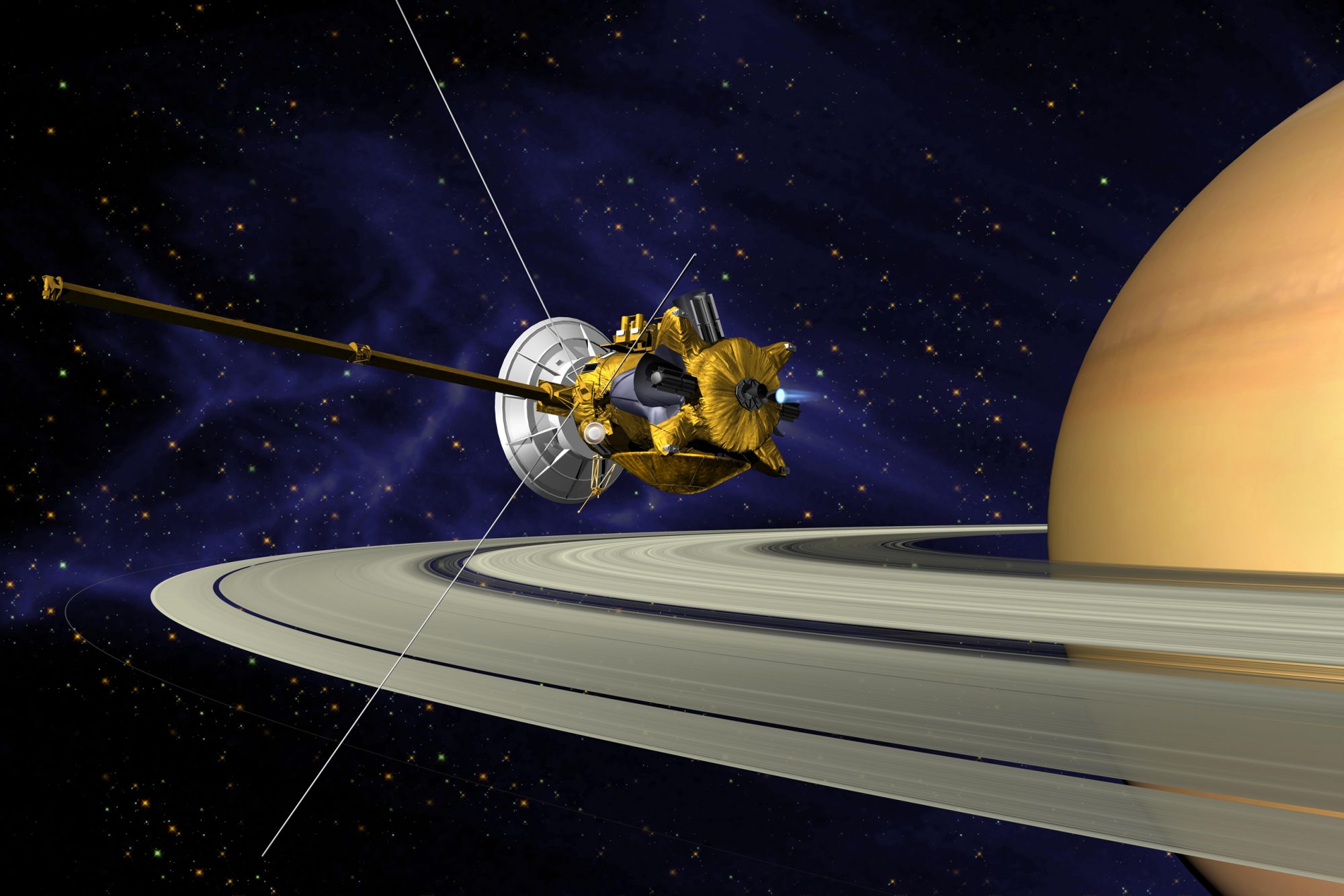

For a big ring system like Saturn’s the leading theory has always been that one of the planet’s moons got too close and was disintegrated by tidal forces generating the trillions of particles making up the rings. As I said that theory has been around for nearly a hundred years but now a new analysis by a team of astrophysicists at MIT is using data collected by the Cassini spacecraft that studied the Saturn system between 200 and 2017.

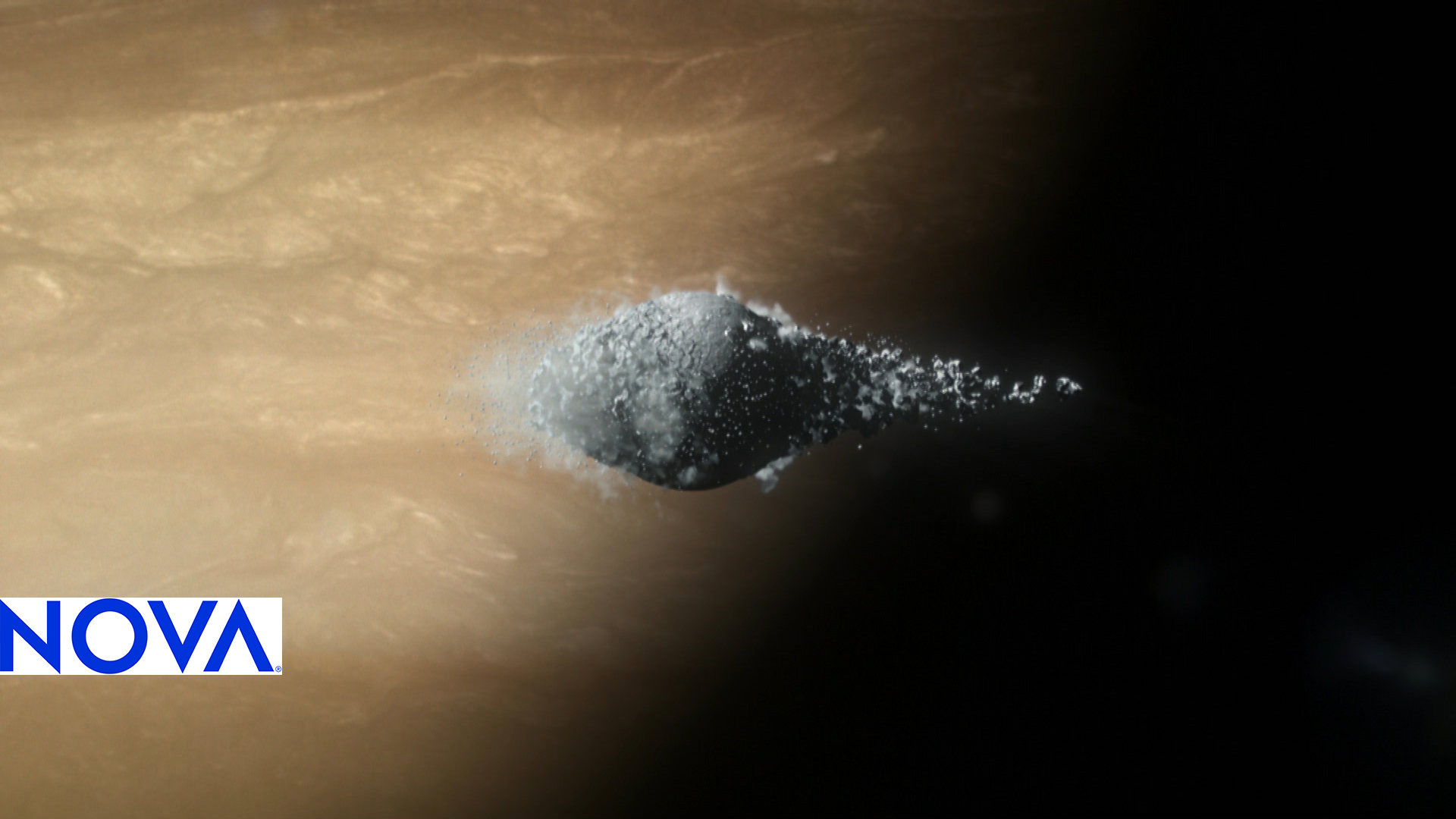

As you may remember, NASA ended the Cassini mission by taking the space probe closer and closer to the giant planet until it finally burned up in Saturn’s atmosphere. By tracking Cassini’s path as it got closer and closer the researchers were able to actually measure the distribution of Saturn’s mass within its body, in other words how much of Saturn’s mass was deep in the planet’s core, how much near the surface etc.

That distribution, technically known as the ‘moment of inertia’ was the missing piece of the puzzle to carry out hundreds of computer simulations of an ancient moon of Saturn, which has been given the name of ‘Chrysalis’ being torn apart by the planet’s gravity to form the rings. According to the simulations Chrysalis was about the size and mass of Saturn’s remaining moon Iapetus, about 700 km in diameter. What happened to Chrysalis is that roughly 160 million years ago the gravity of Saturn’s big moon Titan sent Chrysalis too close to the planet where it broke up. So our best estimate now is that Saturn’s big, beautiful ring system probably formed during the age of the dinosaurs!

The same thing may happen before too long, cosmically speaking with another moon around planet in our solar system. Phobos, the larger, closer moon of Mars is getting ever closer because of tidal forces drawing it towards the planet. It has been estimated that in about 50 million years Phobos will start to break apart giving Mars a ring system of its own.

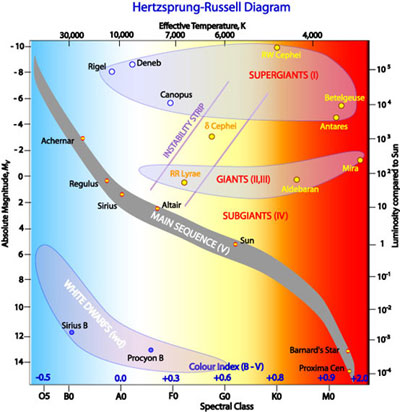

Before I go I would like to mention several news stories that have been circulating about the eventual fate of our own planet Earth. According to the stories, based on a paper published in the Astrophysical Journal, as the Sun uses up its hydrogen fuel its core will shrink and grow hotter until it begins to burn helium as a fuel. As the core gets hotter the outer surface of the Sun will expand turning the Sun into a red giant star like Betelgeuse or Antares. As the Sun’s atmosphere expands it will engulf the planets Mercury and Venus and perhaps even our Earth. the news stories hasten to assure their readers that these events will not occur for another 4-5 billion years.

Well actually that’s all been known since about the 1950s when astrophysicists combined the data from the Hertzprung-Russell diagram with nuclear research to determine the life cycle of stars. That was when the idea that our Sun was a ‘main sequence’ star with a life span of about 10 billion years and was about half way through that span was developed. After the main sequence our Sun will have just about one billion years as a red giant. The question of whether or not the Sun will expand enough to devour the Earth has been debated now for more than 60 years.

What the new study was actually about was what would happen to those planets, Mercury and Venus and maybe Earth, that are engulfed by the Sun as it grows. Once again computer simulations were carried out giving a range of possible fates for those planets but anyway you look at it the planets will certainly be destroyed.

But then nothing lasts forever, even planets.