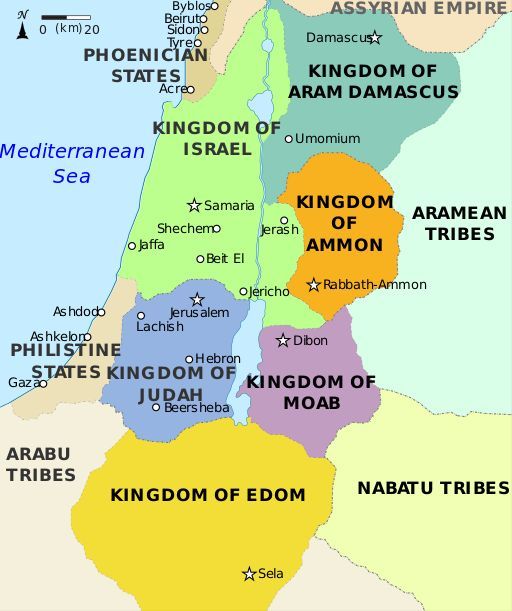

In the earlier sections of the olde testament there are a number of groups of people mentioned who did not survive into later, better historically recorded times and who are therefore something of a historical mystery. The Moabites, Jebusites, Edomites and Ammonites were small tribes who unlike the great empires of Egypt, Assyria and Babylon left little evidence behind of their existence for later historians to study.

For many centuries it was thought that the Hittites were like that, a small nation of people who got swallowed up by the great empires, as the Hebrews almost did, and who disappeared from history. The early 19th century historian Francis William Newman even proclaimed that “…no Hittite king could have compared in power to the king of Judah”. Boy did he get it wrong, in fact the rediscovery of the Hittite kingdom as one of the great powers of the Bronze Age Mediterranean is among the greatest achievements of the science of archaeology.

The first evidence indicating that the Hittites were more important than the bible seemed to indicate was unearthed in Egypt where archaeologists came across numerous inscriptions mentioning the Hittites as an important people. In fact they discovered far more mentions of the Hittites than they did of the Hebrews. The true status of the Hittites really became clear however with the first excavations of the ruins of their capital Hattusa in north central Anatolia, that’s modern Turkey.

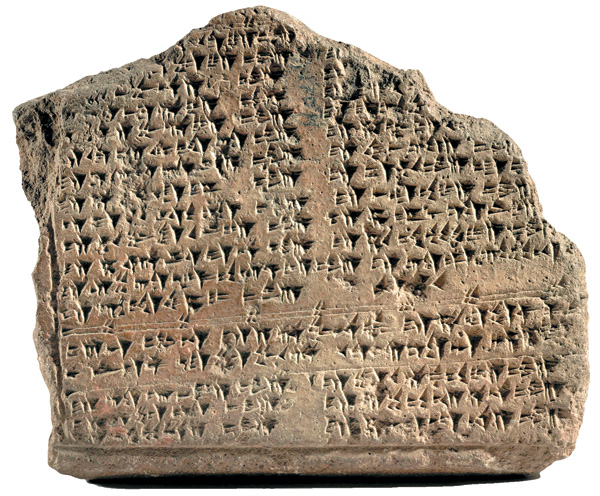

Although the ruins were first discovered in 1884, large-scale excavations of Hattusa only began in 1906 by the archaeologist Hugo Winckler. In addition to determining the full scale of Hattusa, which ranked in size with other great Bronze Age cities like Luxor, Nineveh or Babylon, Winckler also found the royal archives of the Hittite kings, 10,000 clay tablets inscribed in cuneiform but in an unknown language.

In the century since then much has been learned about the Hittite empire, which extended over the central and eastern portions of modern Turkey along with down the coast of modern Syria as far south as Lebanon. It is even thought by some that the city of Troy in what is now western Turkey may have been loosely associated with the Hittite empire.

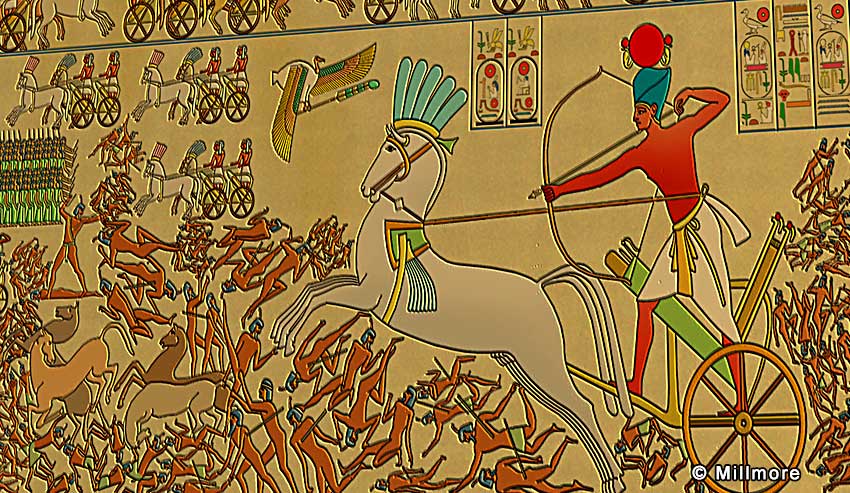

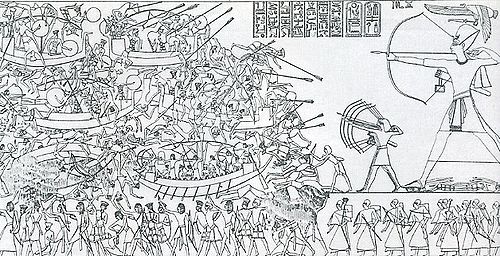

In the time of the Pharaoh Rameses II, 1274 BCE, the Egyptians and the Hitties, under their king Hattusili III fought what may have been the greatest battle of the Bronze Age at Kadesh. The battle was pretty much a draw and five years later the two empires concluded a treaty that lasted more than a hundred years until the collapse of the Hittite empire.

When the language of the Hittites was deciphered from the cuneiform tables it was found to be Indo-European in nature, more closely related to Greek or Latin than Aramaic or Hebrew. Historians are of the opinion that the people who became the Hittites entered Anatolia from either the Balkans or Ukraine around 2000 BCE and either conquered of intermingled with a non-Indo-European people known as the Hattians from who the name Hattusa seems to have come.

The Hittite empire came to an end around 1200 BCE as the eastern Mediterranean world was rocked by a series of invasions by ‘Sea Peoples’ who spread destruction from Greece through Mesopotamia down to Egypt. While Assyria and Egypt both endured the barbarian assaults it was the Hittite empire that suffered the most, the capital Hattusa being burned to the ground around 1180 BCE. For a hundred or so years after that there were several smaller, less powerful nations who called themselves Hittites. Those later Hittite kingdoms did not last long however as they were all swallowed up by either the growing Assyrian empire or by the Phrygian people who settled in western and central Anatolia, and who may have been one of the ‘sea peoples’.

Even after 100 years of archaeological research there is still much that we don’t know, or don’t understand about the Hittite people. One place that has epitomized that mystery is the sanctuary of Yazilikaya, a religious shrine with numerous rock carvings just a short distance from the walls of Hattusa. While the site of Yazilikaya, and its many bas-reliefs have been studied for a century now their meaning had eluded archaeologists.

Now a new paper by a diverse group of scientists claims to have solved the riddle of Yazilikaya. The team includes Serkan Demirel of the department of archaeology at Karadeniz Technical University in Trabzon, Turkey, Eberhard Zangger, President of Luwian Studies in Zurich, Switzerland, Rita Gautschy of the department of ancient civilizations at the University of Basel in Switzerland along with E. C. Krupp, the Director of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, California. By the inclusion of an astronomer in a paper about an ancient temple you can probably guess that the researchers maintain that Yazilikaya, in common with many ancient religious sites, was part temple and part astronomical observatory.

In fact the rock art displayed at Yazilikaya represents both the Hittite view of the structure of the cosmos while at the same time functioning as a calendar. Like many cultures the Hittites believed the Universe to be divided into three parts, the heavens, the Earth and the underworld. Well the shrine at Yazilikaya is divided into two chambers, referred to as A and B. On the north wall of chamber A is a rock carving that portrays the northern constellations that never set below the horizon, like the Big and Little dipper along with Cassiopeia. These constellations are accompanied by carvings of the major gods of the Hittite pantheon, the storm god Teššub, his wife Ḫebat and their son Šarruma and together they represent heaven. On the two side walls of chamber A are carvings of fertility and other more Earthly types of god marching in procession toward the greater gods at to the north. They represent the Earth.

The entrance to chamber B is guarded by lion headed daemons and also contains a three-meter tall statue of Nergal, the god of the underworld. Along the wall of chamber B is a carving of twelve gods of the underworld carrying sickles, a common representation for the gathering of the dead.

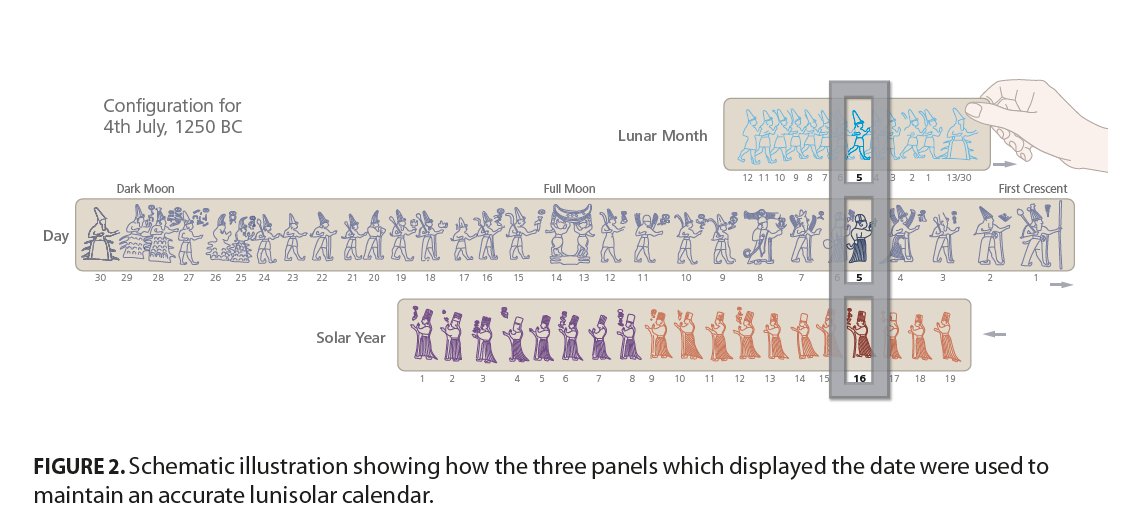

According to the study the sets of carvings, except the northern one, could be used as a calendar keeping track of both the phases of the Moon as well as the days of the year. Such archaeoastronomical alignments and religious observatories in the ancient world are coming to be accepted and studied more and more by archaeologists since the idea was first suggested for Stonehenge back in the 1960s. Many religious ideas and concepts really began as attempts by ancient man to understand the nature and movements of the sky above our heads.

The Hittites were once a powerful, wealthy people whose empire played a leading role in the beginnings of civilization during the Bronze Age. Understanding their culture and religion is necessary if we are to understand how we got to where we are.