Ever since their first manned mission back in October of 2003 the People’s Republic of China, henceforth just China, has been making steady progress in developing their manned space program. As of the writing of this post they have successfully carried out fifteen manned space missions. They have constructed a space station called Tiangong, which they keep permanently manned by routine crew transfer spaceflights. As a part of maintaining Tiangong they have carried out numerous Extra-Vehicular Activities (EVAs). All in all they have step by step acquired all of the skills necessary for living and working in Low Earth Orbit (LOE).

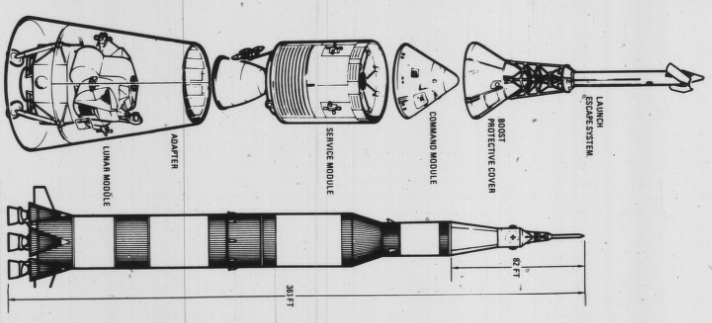

China’s space ambition however extends far beyond LOE, in fact for more than a decade now the Chinese Manned Space Agency (CMSA) has been working steadily towards the announced goal of placing a Taikonaut, their designation for our astronaut, on the Moon by the year 2030. In order to accomplish this task the Chinese need to develop three separate pieces of space hardware, A spacecraft capable of carrying taikonauts from LOE to Lunar orbit and then bringing them back to Earth, a lander spacecraft capable of taking taikonauts from Lunar orbit to the Moon’s surface and then getting then back into Lunar orbit, and finally a big rocket capable of getting the first two spacecraft to Lunar orbit. Of course this is all familiar from the Apollo program with its Command and Service Modules, its Lunar Module and giant Saturn V rocket.

The first of the needed hardware pieces China already has in its Shenzhou spacecraft that has proven itself to be capable of sustaining three taikonauts for periods as long as three weeks. The only modification needed for Shenzhou to be used for a Lunar mission is for its heat shield to be strengthened to withstand the greater heat generated by coming back from the Moon as opposed to just returning from LOE.

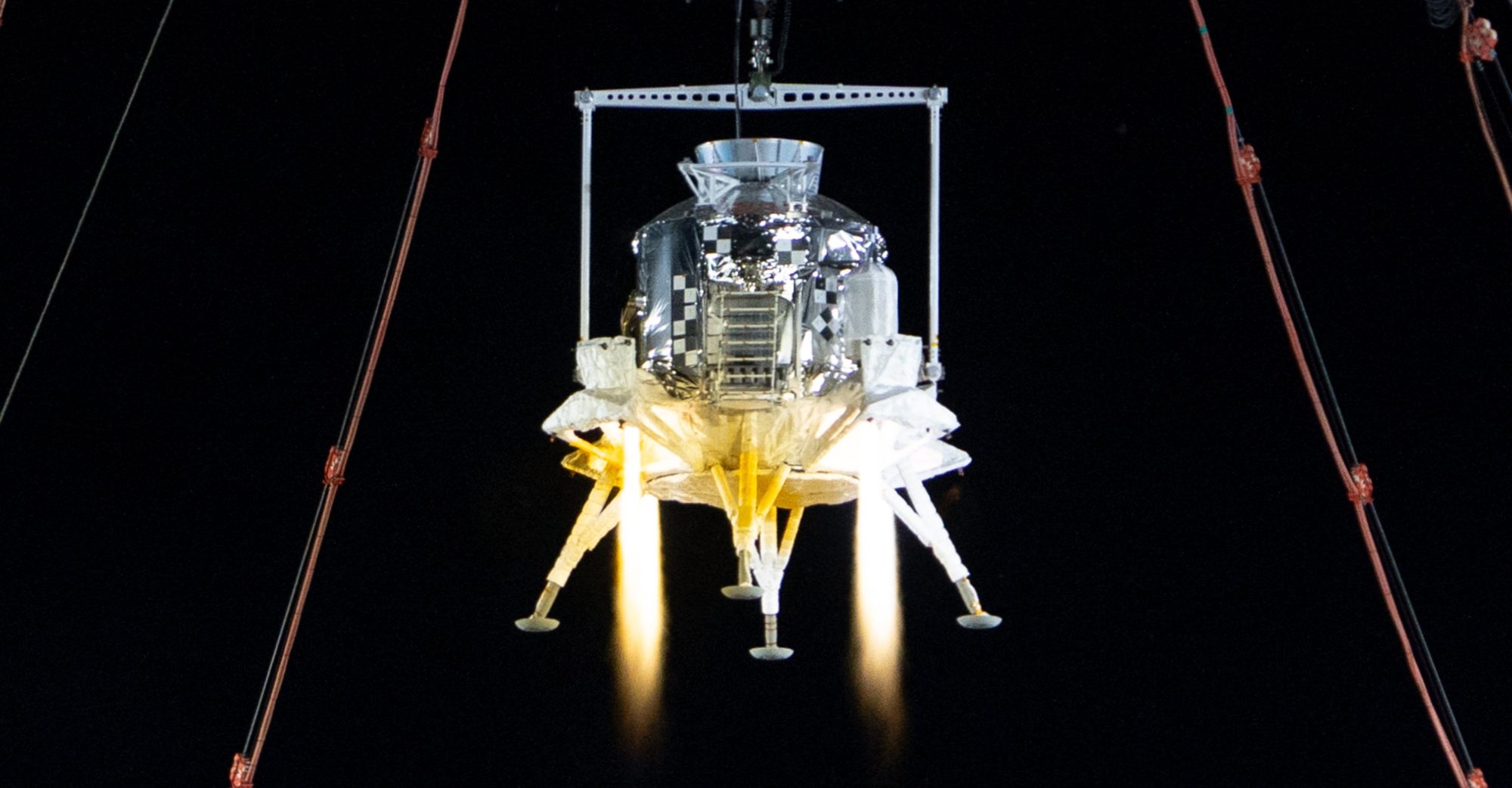

Progress on the remaining two pieces of hardware has again been steady, a word that pretty much sums up China’s space program. In fact two recent tests that have been made public indicate that China is on schedule for their goal of a Lunar landing by 2030. On August 6th CMSA conducted a large-scale test of its Lunar Lander, named the Lanyue, which is Chinese for embrace the Moon. Looking at the image below you can see that the lander module was dangled at the bottom of a large fixture that was itself connected by cabling to scaffolding. This whole setup was in order to replicate the lower gravity of the Lunar surface, only one sixth that of Earth with all of the cabling holding up five sixths of the module’s weight.

During the tests the rocket engines of the lander were ignited and examined for their performance, as were all of the lander’s systems. The successful completion of this series of tests actually puts the CMSA ahead of NASA whose landers for the Artemis program have not yet reached the testing stage.

Then, on the 15th of August the CMSA carried out a static firing of the seven engine ‘core’ of its planned Long March 10 rocket. While the Long March 10 rocket is not designed to have nearly as much thrust as the old Saturn V that took NASA to the Moon the Chinese plan is to use two Long March 10 rockets, one to transport their taikonauts to Lunar orbit and the other to transport the Lanyue lander to Lunar orbit. Once in orbit the two modules will rendezvous and carry out the actual landing.

The test, which lasted for about 30 seconds, demonstrates that the seven YF-100K engines can work together to provide the thrust needed along with other valuable data. Again the test of the engines of its planned Moon rocket is another important milestone in China’s path towards a Lunar landing.

It is worth noting that while the two tests discussed above were made public much of China’s space program is conducted under heavy security, so the costs and any engineering problems that occur remain secret. The two tests were only announced publicly because they were successful, or at least mostly successful. Any problems that might have occurred during the tests were simply not mentioned in the official news reports.

In any case, as China proceeds on its path for manned space exploration, what are other nations doing, or planning to do, in manned space exploration. I’ll skip NASA since most of these posts deal with NASA.

The Russians of course began the space age, shocking the world with their space achievements of launching both the first satellite and the first man into space. What plans do the Russians have for future space exploration? Not much I’m afraid.

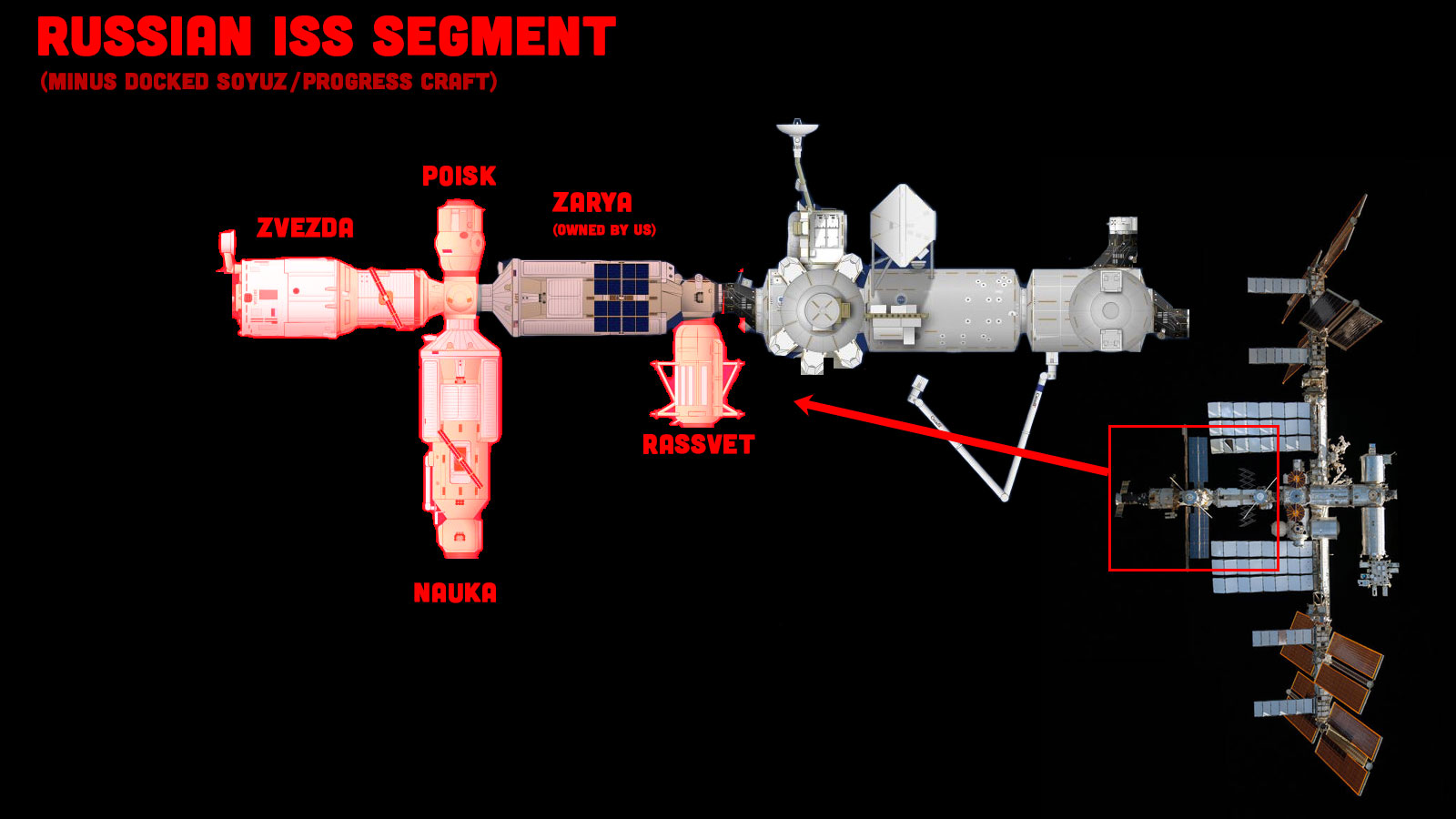

Between the state of Russia’s economy and the costs of their war in Ukraine it appears that Russia has no plans at all aside from taking their half of the International Space Station (ISS) when it is decommissioned in 2030 and trying to build it into a new space station, which they will continue to man with their venerable Soyuz spacecraft. Any plans to go beyond LOE are simply pipe dreams.

The European Space Agency (ESA) has been trying for several decades now to decide whether or not to have its own manned space program or simply tag along with NASA to both the ISS and soon the Moon as it seems Canada and Japan are content to do. There are however several European aerospace corporations that are hoping to tempt the ESA into funding a European Manned Capsule.

A German company named The Exploration Company has developed a cargo-carrying capsule called Nyx. This spacecraft is intended to launch supplies to future space stations but could be modified to carry astronauts. One of the chief selling points of Nyx is that it could be launched into orbit by a number of different rockets.

To demonstrate their capability the Exploration Company recently launched Nyx aboard a Space X Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg air force base. The test didn’t pan out too well however, the capsule did achieve orbit but as it was returning to Earth its parachutes failed to open and the capsule was lost.

Meanwhile a Spanish company named PLD has more ambitious plans, hoping to not only develop a manned capsule Lince that would be capable of carrying four or five passengers into orbit but they are also working on a series of launch vehicles given the name Miura. The first of the series, the Miura 5 is scheduled to make its debut orbital flight next year, 2026.

Finally there is India, which has recently begun to establish itself as a player in the exploration of space as a source of national pride. The world’s most populous nation is calling their manned orbital program Gaganyaan, Hindi for ‘Space craft’ and an unmanned test is scheduled for later this year with a manned mission expected in the first quarter of 2027.

That’s about it, whereas space exploration was once completely dominated by the US and Soviet Union there are now quite a few nations who see space as not only as a way to keep up with the Jones’ but also as a way to develop a technology base inside their country for the sake of their economy.