As I described in several earlier posts, see 6July2024 and 22Febuary2025, one of the prime design goals of NASA’s new James Webb space telescope was to be able to study the early Universe, that is the Universe as it appeared just about one billion years or less after the Big Bang. How does that work, you ask? How can any telescope, even one as advanced as James Webb, see into the past?

Well actually all telescopes look into the past. Because the speed of light is finite, about three hundred million meters per second, if you look at the star Sirius for example, at a distance of 8.7 light years you are not seeing Sirius as it is but rather as it was 8.7 years ago because that’s when the light entering your telescope left Sirius. Similarly, if you look at the North Star Polaris, at a distance of about 500 light years you are seeing Polaris as it was 500 years ago. The distance to the Andromeda galaxy is about two and a half million light years so whenever an astronomer looks at Andromeda they are looking two and a half million years into the past.

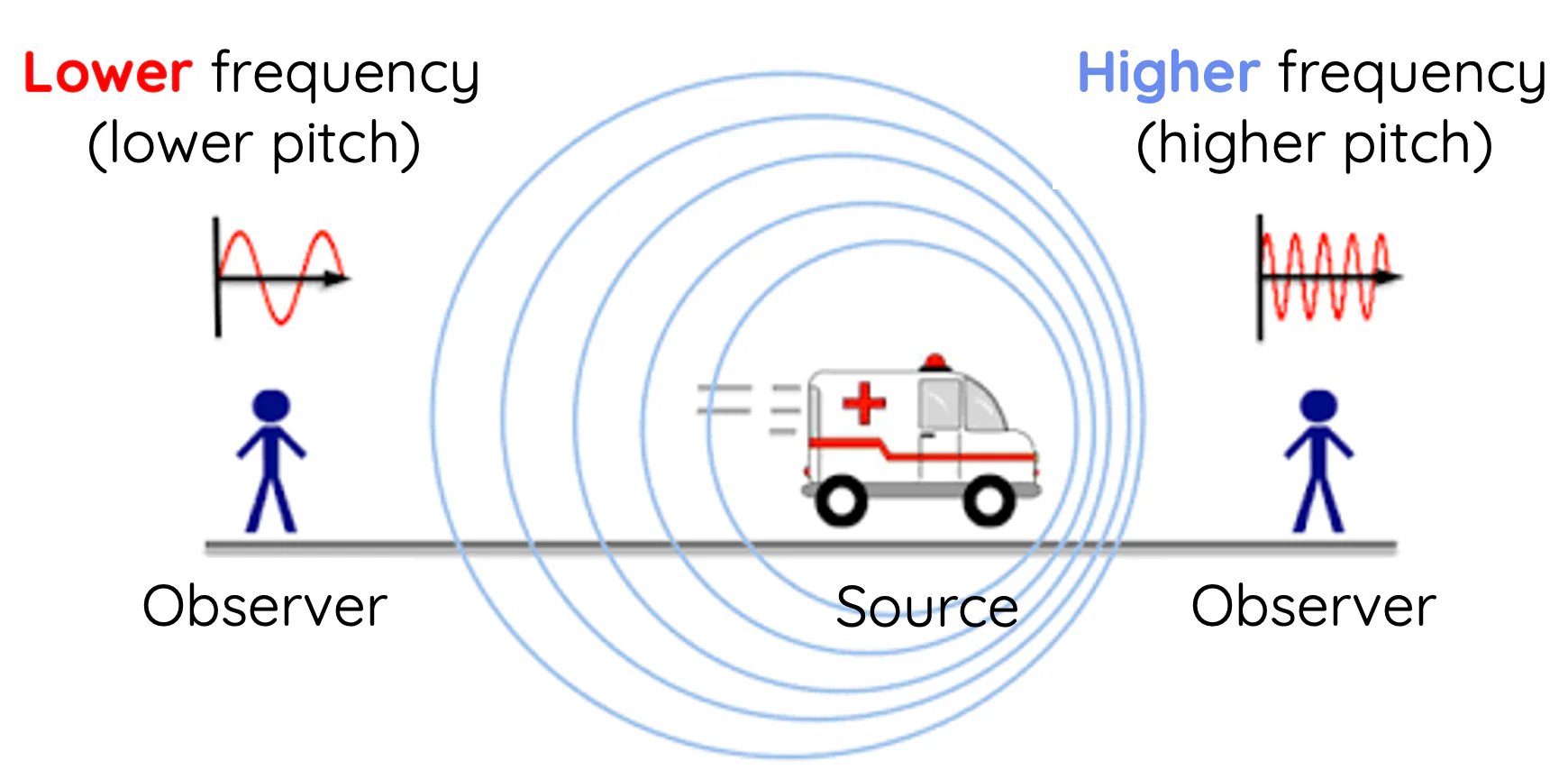

Most galaxies are in fact billions of light years away so astronomers observe them in order to try to understand how the Universe has changed, how the galaxies evolve over billions of years. There’s a catch however, because the entire Universe is expanding, the further away a galaxy is the faster it is moving away from us, and objects that are moving that fast away from us have the light they emit shifted into the infrared due to the Doppler effect.

Which is why the design of the James Webb space telescope was centered around its ability to see in the far infrared. That’s also why the telescope had to be positioned more then a million kilometers from Earth because our planet also emits a lot of infrared light, enough to blind Webb’s sensitive instruments. Astronomers can also use James Webb to study other objects closer to home like the gas clouds where stars are born but first and foremost the space telescope was intended to study the Universe at around one billion years after the Big Bang.

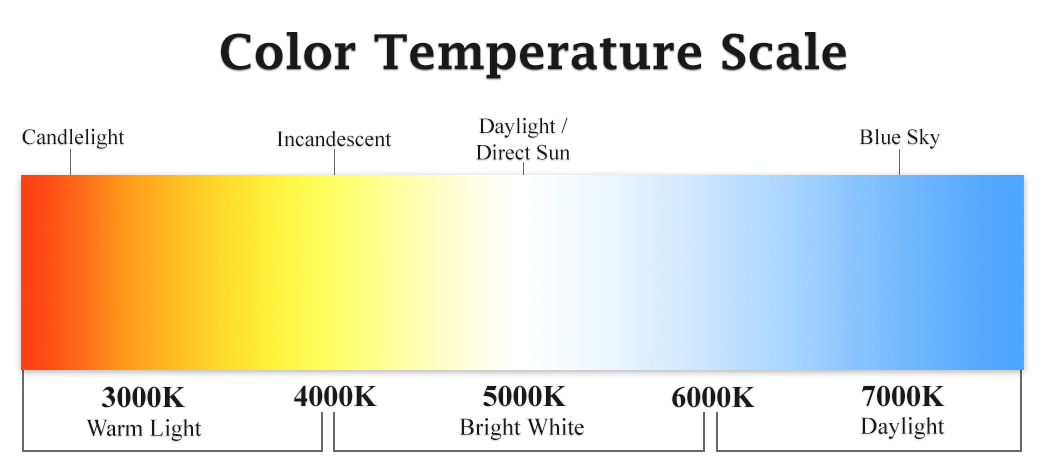

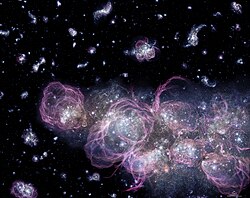

So what did astronomers and cosmologists, physicists who study the Universe as a whole, expect James Webb to find. They had quite a few theories, basically the idea was that about half a million years after the Big Bang the Universe had cooled enough for atoms, mostly hydrogen and helium, to form and when that happened the whole Universe would grow dark because there were no stars yet to emit any light. The theorists expected that gravity would cause the first stars to form around a half billion years after the Big Bang and based on their calculations those first stars would be really big ones, very bright, very blue in colour. A few hundred million years later those first stars would then be clumping together to form the first galaxies.

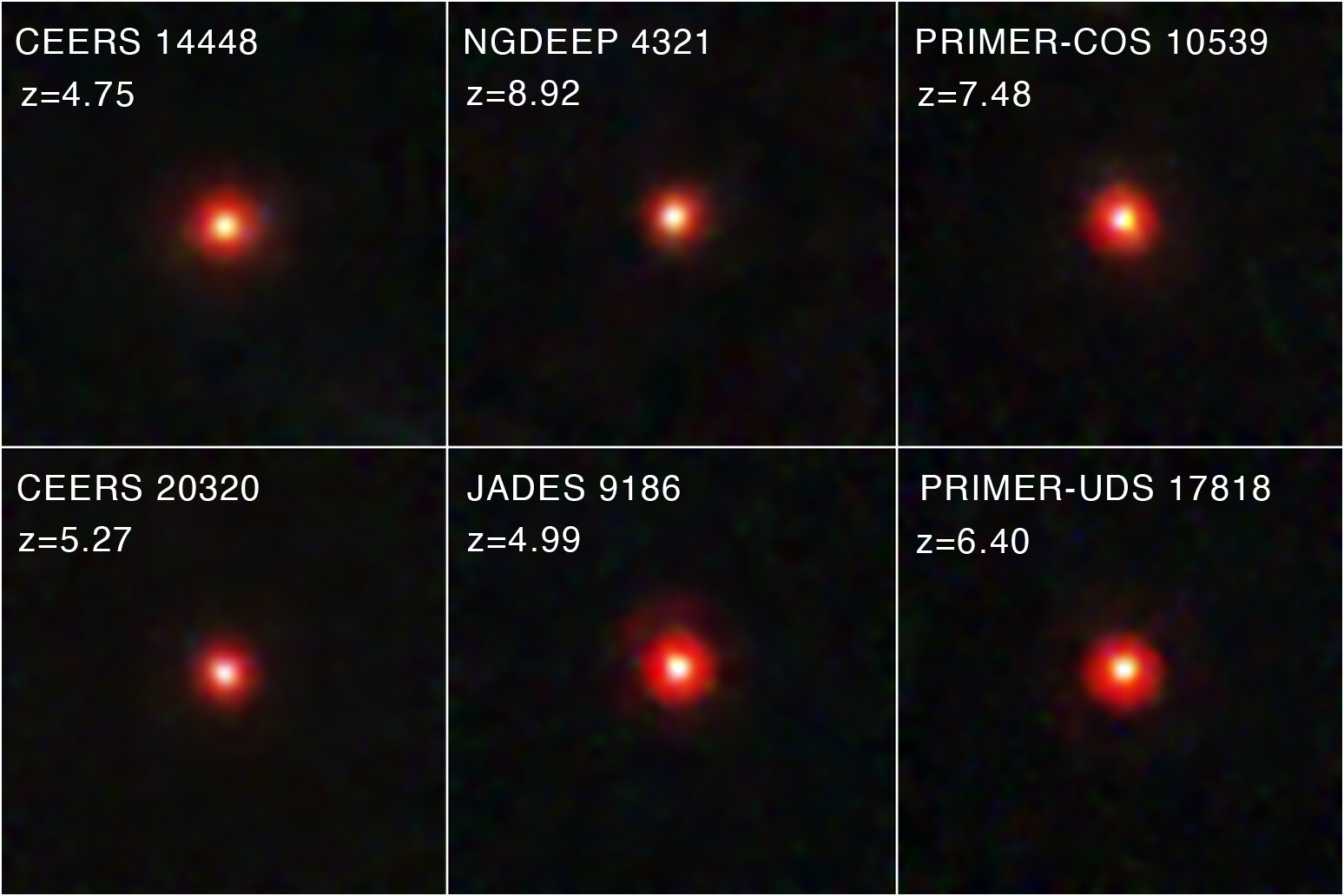

That’s pretty much what astronomers expected James Webb to see, small, simple galaxies containing a few million or so really bright stars. Instead what they got as they studied the first images from James Webb almost three years ago now were a bunch of ‘Little Red Dots’ (LRDs).

Colour means a lot to an astronomer, red stars are actually cool while blue or violet stars are much hotter so the LRDs that Webb imaged were not the big bright stars that astronomers were expecting. At the same time the objects seemed to be too small to be any kind of galaxies. For these reasons, among others the LRDs were initially called ‘Universe Breakers’ because they went against all of our theories about the early universe at that time.

Trying to come up with some kind of model to describe the LRDs astrophysicists first suggested that they were small but well formed galaxies with millions of red stars packed in real tight. The idea of such compact, well organized objects already existing just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang was so outrageous is the reason why astronomers considered them to be Universe Breakers. One thing everybody agreed on was the need for more data; especially we needed the spectrum of a few of these LRDs. The early Universe cosmologists had to wait their turn however, as other programs got their first chance with Webb.

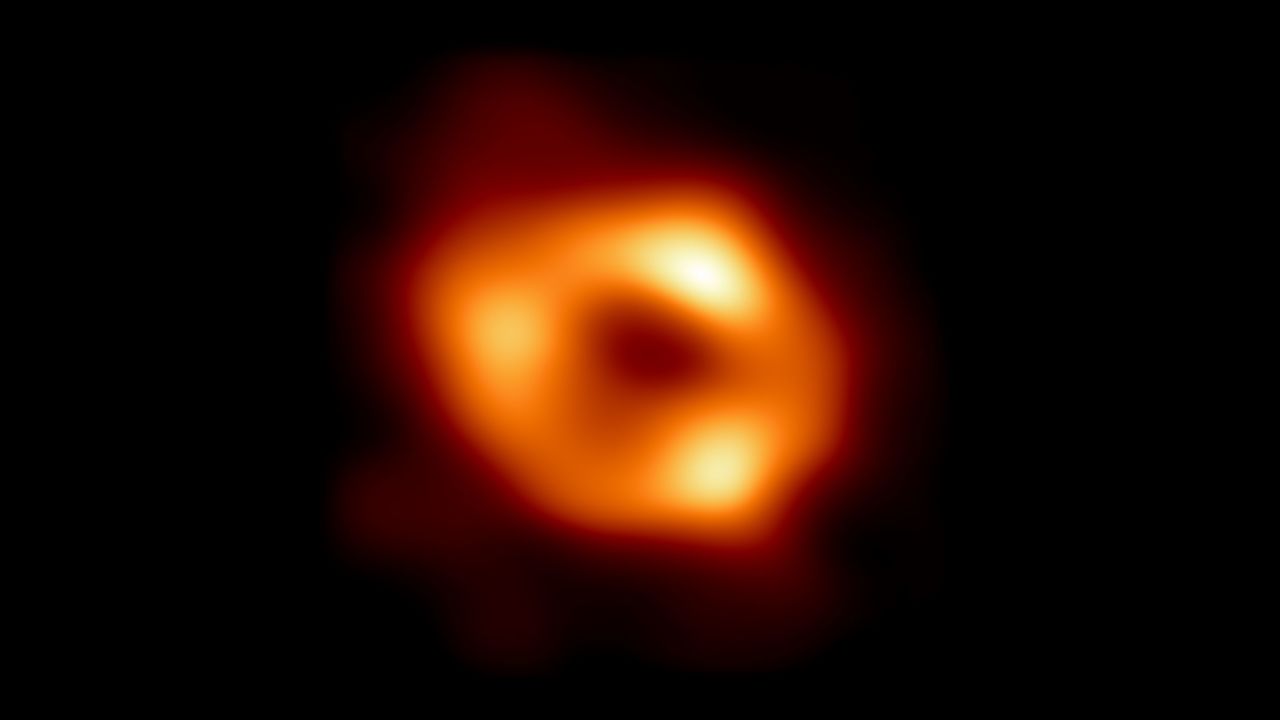

Eventually Webb did return to observing the early Universe and succeeded in obtaining the spectra of some of the LRDs and that better data has caused a shift in thinking about what they could be. The latest model for the LRDs is a black hole that has succeeded in pulling so much material around itself that it looks much like a very large but very cool star.

In a paper from the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics with lead author Anna De Graaff these objects have been named ‘Black Hole Stars’ because even though they get their energy from matter falling into a black hole at their center, their atmospheres closely resemble those of red dwarf stars. The researchers also suggest that the LRDs are in fact the early stages in the development of the Supermassive Black Holes that are now considered to be at the center of every big galaxy.

If that analysis is true, and there’s still a great deal to be learned about the LRDs, then James Webb has given us the answer to a question that has been bouncing around for the last twenty years or so. Which came first, do galaxies form supermassive black holes in their centers or do supermassive black holes form galaxies around them. If LRDs are baby supermassive black holes then before long Webb should find some of them with proto-galaxies around them.

When, and if that happens the astrophysicists will have the data they need to rewrite their theories of how galaxies form. Then we will know more about how our Universe came to look the way it does.