The argument over Pluto’s status as a full fledged planet or not has been going on now for almost 14 years and there appears to be no end in sight. I grew up without ever questioning Pluto’s designation but admittedly even back in the 1960s Pluto was considered something of an oddball for a planet. Smaller even than Mercury, much smaller than it’s gas giant neighbors Pluto’s orbit even occasionally brought it closer to the Sun than the eighth planet Neptune. Crossing the orbit of another planet seemed like something no self-respecting planet would ever do.

Then, starting in the 1990s a number of other icy bodies with even more unusual orbits were discovered not far beyond Pluto. These objects were grouped together as Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) and the debate over what kind of body Pluto was, a planet or a KBO began.

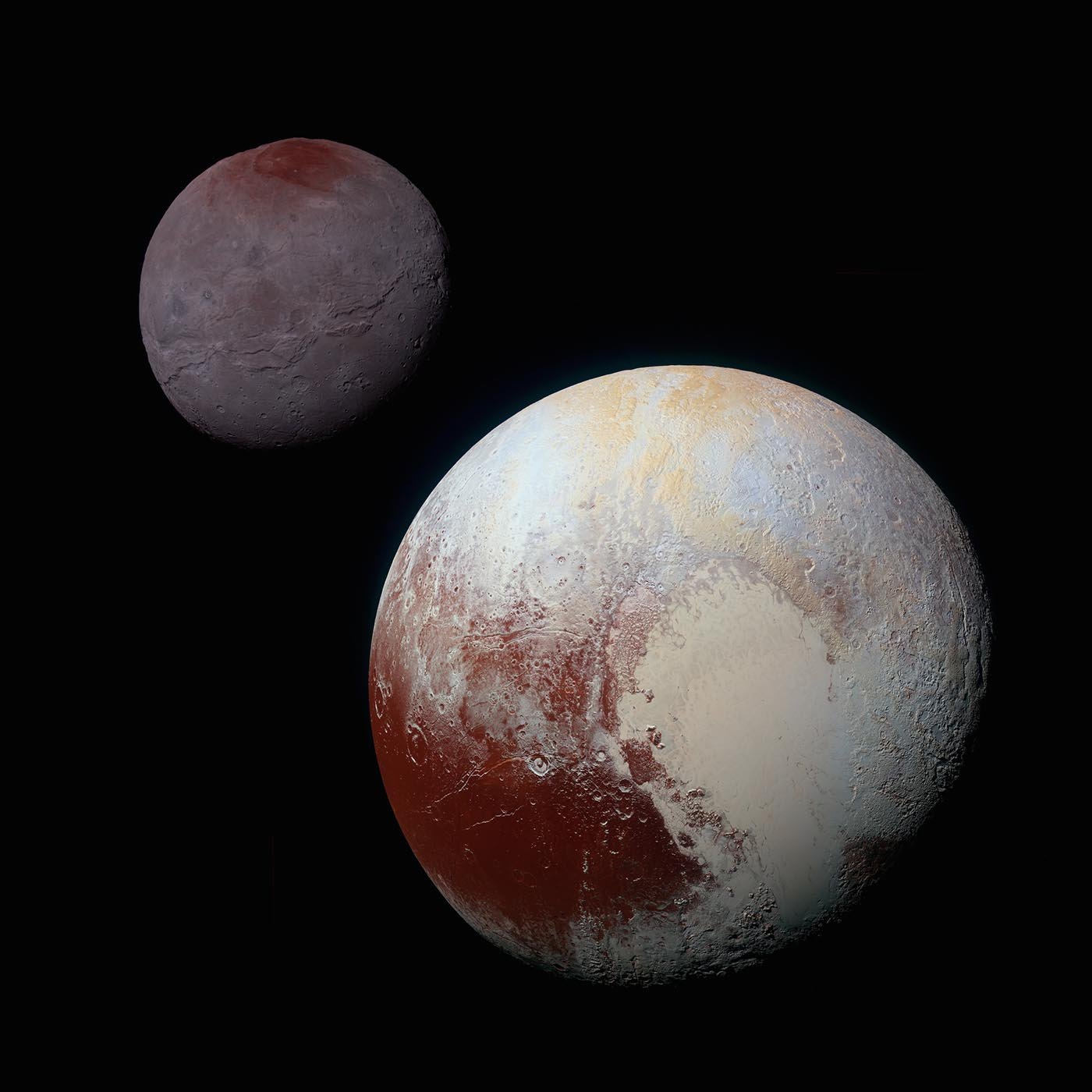

The current definition of a planet basically consists of two criteria. One, a planet must be large enough, massive enough that it’s gravity pulls it into a nice spherical shape. Pluto passes this criterion easily, as does Ceres in the asteroid belt.

The second criterion is that a planet’s gravity must be strong enough to sweep out any other object from its orbital region. This is the test that Pluto and Ceres both fail. Ceres fails because of the other asteroids while Pluto fails because of the other KBOs. That is the official position and I don’t intend to take sides one way or the other. I’ve never liked arguing over definitions. To me Pluto is what it is no matter what we choose to call it.

All of which has nothing to do with today’s actual topic, the continuing search by astronomers for an as yet undiscovered ninth planet, a tenth planet if you insist on Pluto being a planet. So why do astronomers think that there could be another planet out there, and how are they going about looking for it?

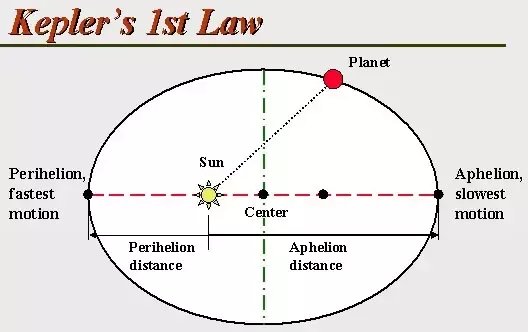

It all has to do with the pulling and tugging that the gravities of the planets have on each other’s orbit around the Sun. Because the Sun’s mass is so huge, about 500 times the mass of all of the planets, moons and everything else in the solar system added together, the orbits of the planets are pretty close to ellipses, just as Kepler’s first law requires.

Nevertheless the pulling of the gravities of the other planets does have an effect that astronomers can measure and compare to their calculations. If any discrepancy is found, even the tiniest will cause astronomers to start searching for the cause.

This happened in the first half of the 19th century when the measurements of the orbit of Uranus, the seventh planet, did not match calculations. It was suggested that another planet beyond Uranus might be the cause and after twenty years of calculations planet number eight, Neptune was found exactly where the math said it would be.

Then the same thing happened to the orbit of Neptune, the planet wasn’t quite moving as the calculations said it should be. So the hunt was on for a ninth planet, which finally led to the discovery of Pluto in 1930. Pluto was so small however that it didn’t seem able to account for all of the discrepancy in Neptune’s orbit. So, for the next five decades astronomers kept looking for a tenth planet beyond even Pluto without success.

Things have gotten a lot more complicated since then, and I’m not talking about whether or not Pluto is a planet. I mean with all of those Kuiper Belt Objects orbiting around out there it’s difficult to calculate just what all is going on. Do the KBOs together account for the problem with Neptune’s orbit or do we still need another planet, or would several more KBOs do the trick? And what about the orbits of the KBOs themselves? Are their orbits matching the calculations or does it seem as if there could be another big body out there affecting their motions? Plotting the orbit for one object in our Solar System is a lot of math, even using a computer. I know, I had to do it back in grad school. Trying to do the same for the over 1500 known KBOs is beyond my programming skills.

Fortunately it’s not beyond the skills of Samantha Lawler, Assistant Professor of Astronomy at the University of Regina in Canada. Using observations and discoveries made by the Outer Solar System Origins Survey Dr. Lawler, no relation, has calculated the orbits of the known KBOs for the purpose of finding where that ninth planet could be hiding. If it exists that is.

A fair amount of Dr. Lawler’s work actually consisted of recognizing observational biases in earlier searches for KBOs. First of all since KBOs are so far from the Sun they hardly move at all against the background of fixed stars. Because of that the regions of the Kuiper belt that lay in the same direction as the Milky Way have been ignored because of the enormous difficulty in distinguishing a small icy body from one of the millions of distant stars in our galaxy. Other biases arose when certain telescopes were employed in searching the Kuiper belt during certain times of the year, again neglecting whole sections of the solar system.

Adjusting for these biases in her simulations Dr. Lawler has shown that KBOs are actually more uniformedly distributed that other surveys had indicated and that the orbits of the known KBOs can be explained without the need for the gravity of a ninth planet to shepherd them.

So it appears that there probably isn’t another planet out there beyond Neptune and Pluto waiting to be discovered after all. Instead there are thousands of small, icy KBOs. Tiny little worlds that never managed to come together to form a single big planet.

Maybe, in some ways that’s even more interesting.