Nowadays most of us carry a camera with us wherever we go. The cheap little digital cameras in our phones can capture images that are often superior to the images taken 50 years ago by professionals using the best equipment of their time. It’s hard to imagine that photography is only a little more than 200 years old and that it was once a very difficult combination of art and science.

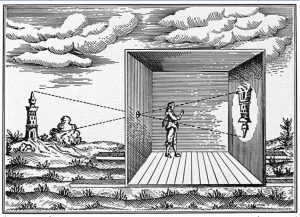

The word camera itself is Latin for room and really applies to the box which light can only enter through a pinhole opening. Such a device is known as a ‘Camera Obscura’ and way back in ancient China it was found that the light coming through the pinhole would project an inverted image on the opposite side of the box. See the image below for a diagram of the operation of a Camera Obscura.

It was in the year 1800 that Thomas Wedgwood attempted to capture the image in a Camera Obscura by means of a sheet of paper that had been soaked with the light sensitive chemical silver-nitrate. Wedgwood did succeed in making a shadowy image however the silver-nitrate was so unstable that the image faded after only a few days.

It was the Frenchman Nice’phore Nie’pce who placed a lens where the pinhole had been and produced the earliest surviving photograph in 1826. Known as ‘The View from the Window at Le Gras’ the image took several days exposure to complete, that’s how much light was needed to alter the silver nitrate. The image of “The View from the Window at Le Gras’ is below.

Obviously photographs that required hours or even days to produce were not going to be a big commercial success. It wasn’t until 1839 when Louis Daguerre discovered a way to make the images formed by using silver halides permanent that photography became more than just a science experiment. Daguerreotypes as they were known were produced in the thousands with many historical and artistic firsts. These include the first photographs of world leaders, see the earliest known photo of Abraham Lincoln below, and the first photograph of a Solar Eclipse, taken on July 28, 1851 and also shown below.

Even Daguerreotypes fade in time however, and today some of the oldest known photographs are so degraded that their images are all but lost. Lost that is, except for the work of researchers at Western University and the National Gallery of Canada. Led by Madalena Kozachuk, a Ph.D. student at Western’s Department of Chemistry the researchers used rapid-scanning micro-X-ray fluorescence to measure the Daguerreotype’s remaining mercury, used in the development of the image after exposure.

By making a point by point measurement, taking eight hours to complete, Kozachuk succeeded in restoring the images. Looking at the side by side comparison below of a Daguerreotype of an unknown woman it is easy to see how well the process works.

There are thousands of Daguerreotypes stored in libraries around the world; the National Gallery of Canada itself has over 2,700. Madalena Kozachuk’s technique allow enable conservators to bring back some of our earliest photographic history.

Think about that the next time you pull out your smartphone and start snapping some selfies!