“All animals are equal,” George Orwell declared in his novel ‘Animal Farm, “But some animals are more equal than others!”

The question of when and how did social inequality arise in human populations has been asked ever since we humans began to live in large societies. Now let me be clear here, I’m talking about social inequality, the kind of inequality where a small but recognizable portion of a human population dominates and forces obedience from the greater part of their society for periods of time longer than a single human lifespan.

We can see the beginnings of this inequality in the social behavior of our closest relatives. In a troop of chimpanzees or gorillas the alpha male and his close companions push the rest of the group around establishing a easily recognizable pecking order. However it is rare for that dominance to be passed directly to the son of the alpha male. Strength, not pedigree is the key to being on top in such primitive societies.

The opinion of most anthropologists is that long term social inequality requires material wealth. Objects such as tools or pottery but most importantly weapons that an alpha male can pass on to his son(s) giving them an advantage over the other members of their tribe. Eventually the ability to pass on the ownership of flocks of domesticated animals or land itself will bring with it the establishment of actual economic classes, rich and poor.

Now Stone Age societies are known to have possessed a degree of material wealth in the form of stone and bone tools and in later periods even pottery. However stone tools and pottery break quite easily and are of little permanent value.

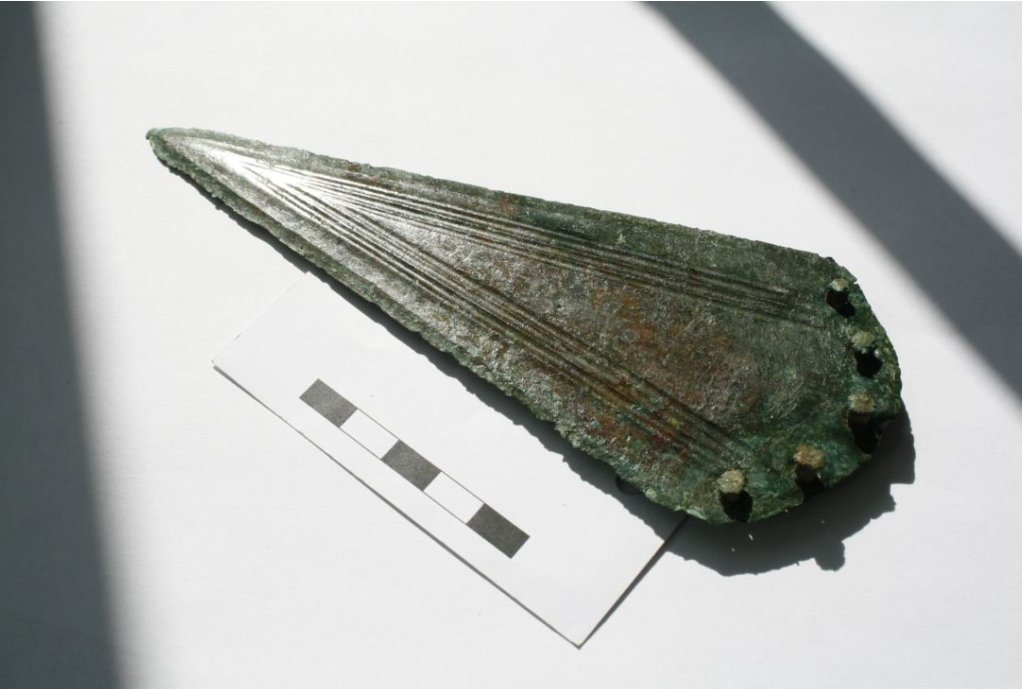

Metal makes all the difference. Metal tools can last for many years with care and a metal weapon will not only keep its edge far longer than a stone one but can even be resharpened when it does become dull! The long-term value of metal objects appears to have been a real game changer in the evolution of human civilization.

Therefore, the argument from anthropologists goes, the first evidence for the development of social inequality should be found in the Bronze ages. The question is therefore; does the evidence of the archeological record support that argument?

There is a wealth of data from the Bronze Age civilizations of the eastern Mediterranean that seems to confirm this hypothesis. The pharoses of Egypt were treated as god-kings who could command tens of thousands of commoners to build their massive pyramid tombs while the Hittite and Mycenaean Greek Kings lived in enormous palaces surrounded by the common folk who laboured for them.

But what about the rest of the world, is there any evidence for the rise of social inequality in the rest of Bronze Age Europe for example? It’s that question that makes the recent study of the Late Neolithic to Early Bronze age site in the Lech Valley in Germany so interesting.

Authored by Alissa Mittnik and Johannes Krause of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History along with Philipp Stockhammer from the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet in Munich, the study makes extensive use of the latest archaeological techniques, radiocarbon dating, DNA analysis and isotope analysis of tooth enamel along with more traditional methods.

The Bronze Age sites in the Lech valley consist of several large homesteads, numerous smaller farms and critically, several cemeteries. Those cemeteries yielded the remains of 104 individuals that were radiocarbon dated to a period between 2800 and 1300 BCE, spanning the late Neolithic to early Bronze Age.

The presence of a wide assortment of grave goods in some of the graves allowed the identification of upper class versus lower class individuals according to criteria employed since the beginning of archeology. For example the presence of bronze daggers or axes in a male grave, or metal jewelry in a female grave would indicate a member of the warrior elite while few or no grave goods is indicative of a servant or serf.

Once a set of remains had been classified as to its social status DNA extracted from teeth or bone was used to determine their family relations. The researchers discovered that the upper class warrior individuals had no family relationships at all to those of the lower class. At the same time they were able to establish father to son sequences within the upper class that could last as long as five generations. Also, isotope analysis of chemicals extracted from the tooth enamel of both the high-class males and all lower class individuals showed that they were all native to the Lech valley.

The surprise of the study however turned out to be the examinations of the high-class female remains. Genetically the high-class women showed no relationship to either the high class or lower class men! In addition when the tooth enamel of the high-class women was chemically examined it was found that they were foreign born, some coming from as far away as modern Czechoslovakia, more than 500 kilometers away. The implication is that these women were brought to the Lech valley to be wives for the high-class men while the daughters of the high class were sent elsewhere to marry.

This cultural tradition of aristocratic families sending their daughters to marry into families at great distances is believed to have served two purposes. First it prevented inbreeding within the upper class while at the same time it helped to establish cultural and even trading links with other communities. While such nuptial customs are well established for the late Bronze and through the Iron Age into the Roman period this study provides the first comprehensive support for the existence of these traditions at the very beginning of the Bronze Age.

With every new excavation, with every new technique developed to examine the finds unearthed the science of Archaeology is discovering more and more about the beginnings of human civilization. This includes the story of when and how human social classes first developed.