Human beings have a tendency to overlook or even ignore those things that are the most familiar to us. Because we see something all of the time we feel as if we know everything there is to know about it, it just isn’t interesting anymore.

The chicken has been treated that way throughout history. Entire cultures have been built around cattle or sheep or the bison but not the chicken. Even when a small flock was kept just outside the house for the occasional egg or a special meal it was always the bigger livestock that got all of the attention.

Nevertheless, today it is the chicken that has become humanity’s largest supplier of protein. Today there are more domestic chickens being raised for food than any other animal. The chicken is the greatest success story of the technology of industrial food production, and as a living creature the chief victim of that success.

Andrew Lawler’s book ‘Why did the Chicken Cross the World’ is a journalistic investigation into the chicken, from it’s natural state as a wild bird spread across southern and southeastern Asia to being little more than one of the farmer’s wife’s chores to becoming one of the most valuable industrial commodities on the planet.

No one knows when human beings first began to keep the small wild relative of the pheasant but the remains of chickens along with primitive pictograms identified as chickens indicate that our relationship dates back into the Stone Age. The earliest evidence for humans raising and breeding chickens is not for food however, it was for cockfighting.

Indeed much of the first third of ‘Why did the Chicken Cross the World’ deals with cockfighting as both a vehicle for gambling but also as a religious ritual! Andrew Lawler presents his evidence in a clear, enjoyable fashion that I quite frankly envy. Traveling around the world Mr. Lawler visits a selection of people who raise roosters for the pit but whose affection for their fighters is much more than just a source of income.

Moving forward in history Mr. Lawler details how for centuries the chicken competed with ducks and geese, and later the American turkey, for a place in humanity’s farms. It was only in the late 19th and early 20th century that the chicken became the dominant barnyard fowl.

It is the story of how the chicken became the most numerously bred, raised and finally, slaughtered animal that is the main part of ‘Why the Chicken Crossed the World’. Starting about 1850 in England and the US the importation of larger, meatier chickens from Asia began a long term breeding program to produce a chicken that would grow bigger in less time for less feed making chicken more available and less expensive.

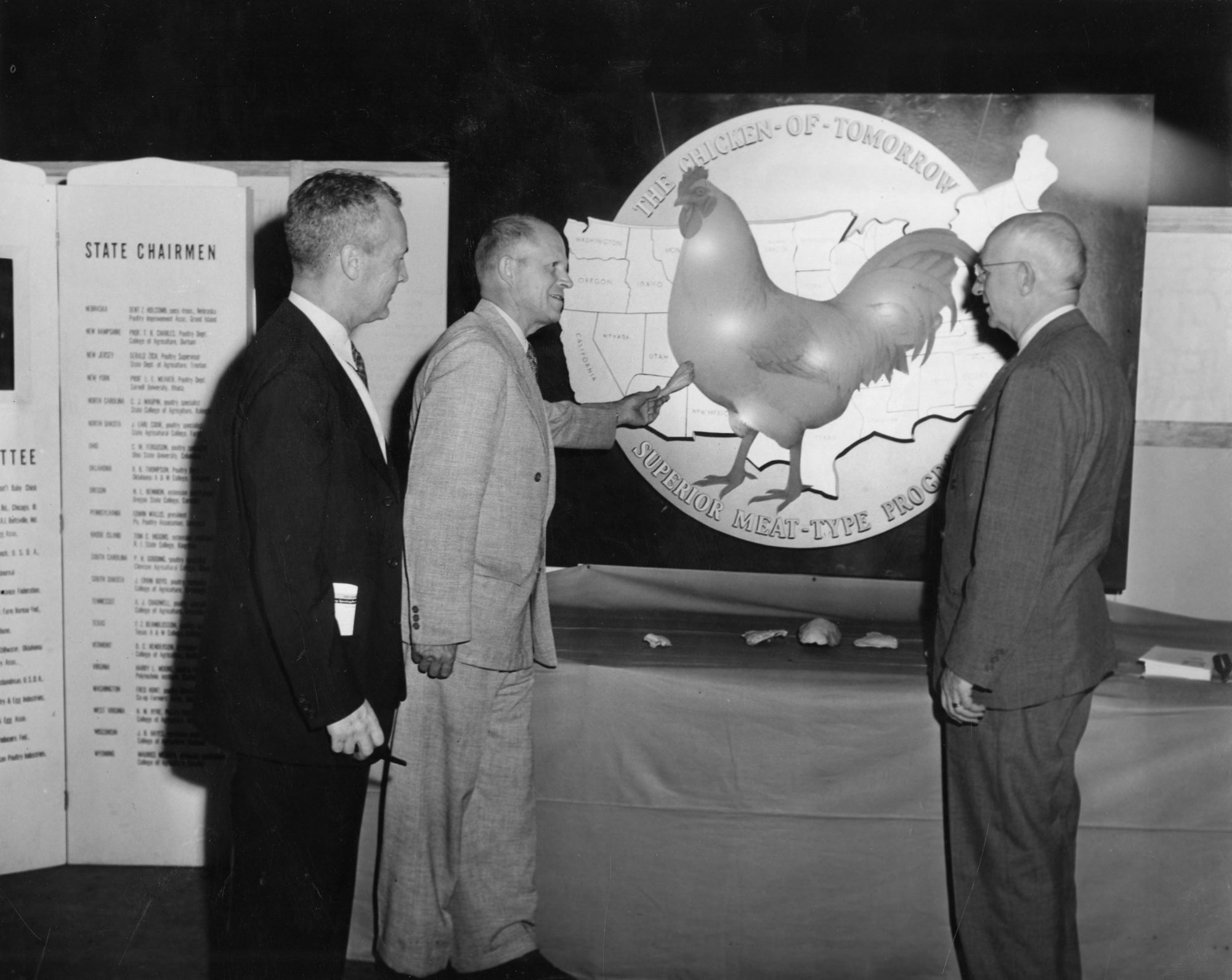

A key moment came in 1948 when the world’s largest retailer, the A&P supermarket chain joined with the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) to sponsor the ‘Chicken of Tomorrow’ contest. The winner of that contest became the sire of an industrial production line of chickens that grow to more than twice the weight of their wild ancestors. In as little as 47 days modern birds are fully grown at a ratio of one kilo of chicken produced for two kilos of feed, a ratio that is nearly 50% better than any other species of meat producing animal.

None of this did the chickens any good. If they are bred for meat they are stuffed by the tens of thousands into industrial sized coops, see image below, where they are fattened up to the point where they can hardly stand. They are allowed to live for less than two months before being slaughtered.

If they are bred for egg production they are squeezed into a tiny ‘battery cage’, see image. They lay an egg a day on average, a process that takes so much calcium out of their systems that their bones are extremely weak. After a year the hen is so exhausted that she is simply used for dog food.

That’s the hens, the roosters, which are not as valuable and harder to keep because of their tendency to fight, are simply separated from the hens after hatching and disposed of in as cheap a method as possible. To the modern food industry the chicken is no longer a living creature but just another commodity to be produced and packaged cheaply and efficiently.

A motif that Mr. Lawler often returns to is that for millennia the chicken as an animal was a familiar animal. Today it is virtually unknown as a living thing; it is just something we eat, a commodity not a fellow creature.

‘Why the Chicken Crossed the World’ is a thoroughly enjoyable book. A mixture of science, technology, history, sociology and politics in which you find yourself learning something on every page and the knowledge sticks with you. And I’m not just saying that because Andrew Lawler and I share our surname. To be best of my knowledge we are totally unrelated, the book is just really good!