Ever notice how just a few places on Earth get all of the press coverage when it comes to evidence of ancient civilizations. Egypt of course heads the list closely followed by Greece, Mesopotamia and Central America. Then there are certain specific ancient sites that gather a lot of attention like Stonehenge or China’s terra cotta warriors. Media coverage of archaeology is minimal at best and news directors aren’t going to give precious airtime to a story from some part of the world that the average viewer doesn’t associate with archaeology.

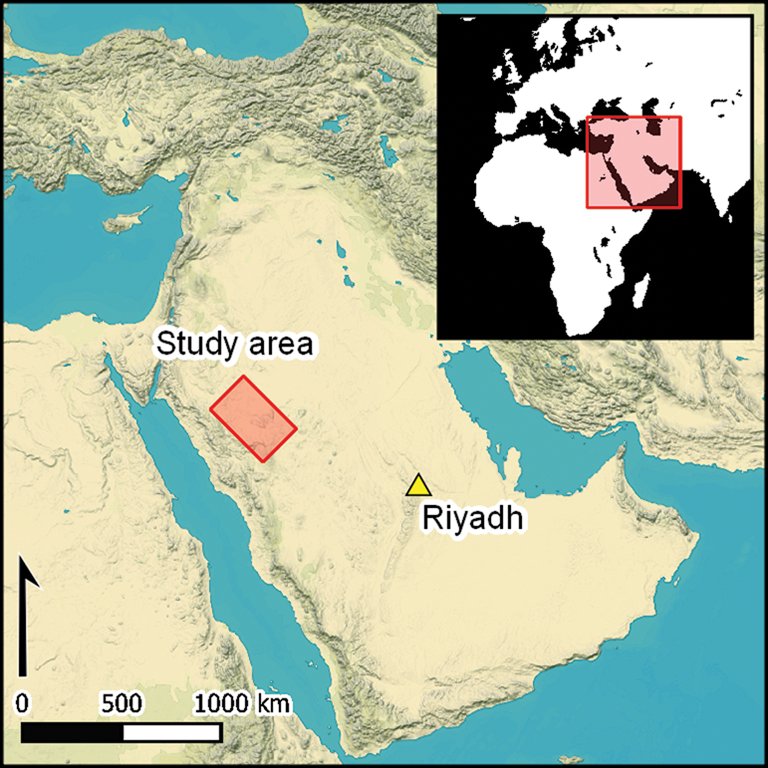

Well I will! This month’s stories come from such far-flung places as Laos, the Arabian Desert and Ireland. (O’k maybe Ireland does have some well-known ancient sites like Newgrange along with a wealth of Stone Circles but this is the first time I’ve ever heard of an archaeological discovery coming from Laos!) Let’s begin with the remains that are considered to be the oldest, the mysterious mustatils of the Arabian Desert.

Mustatil is from the Arabic word for rectangle and they typically consist of a rectangular shaped stone enclosure as small as 20 meters to as long as 600m meters with sandstone walls averaging less than 1.5 meters in height. Over one thousand of these structures are known from the northwest corner of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Excavations of several mustatils have revealed a chamber in the center of the enclosure that contained the bones of cattle and other animals such as sheep, goats and gazelle. Carbon-14 dating of the animal remains have given dates as far back as 5000-5300 BCE, more than 7000 years ago.

The low height of the enclosure walls makes it unlikely that the mustatils were used as corrals and other signs indicate to archaeologists that the structures were used for ritualistic purposes. As such the mustatils may be the first evidence of a cattle cult in the Arabian Peninsula and in fact may represent the earliest known religious structures on Earth. Indeed the number and variety of animal remains at the mustatils are also evidence that thousands of years ago the Arabian Desert was a much more fertile grassland than they presently are.

Mustatils only became known to the scientific community in the 1970s and have still only been superficially studied. However the Saudi Royal Government has begun funding a project to carry out more thorough investigations. Part of those studies will be undertaking by the Aerial Archaeological in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Project (AAKSA) in the hopes of identifying and cataloguing all the mustatils.

By contrast the known archaeological sites of Ireland have already been rather thoroughly surveyed and any major new discoveries now rely on the chance unearthing of previously undiscovered remains. Just such a discovery occurred a month ago in April on the Dingle Peninsula of County Kerry as workmen who were making improvements to a farm unearthed a stone lined burial chamber known as a “cist”. The grave was discovered when the workmen were using a backhoe and overturned a large flat stone used to cap the tomb revealing what lay beneath.

Fortunately the workers immediately notified National Monuments Service and the National Museum. An initial examination indicated that the grave was likely to date from the Bronze Age, around 2500 BCE and best of all, the entire site appears completely untouched.

A small sample of the skeletal remains were removed and sent to a labouratory for carbon-14 dating and an unusual find of an oval shaped polished stone was discovered next to the body. There are also indications of an adjacent sub-chamber at the front of the cist. A full excavation is being planned and should commence soon. This region of Ireland is well known for its ancient burials so it is possible that further discoveries could be only a few meters away beneath the ground.

The stone Jars of the ‘Plain of Jars’ in the country of Laos may be easier to find but they are no less mysterious. In fact let’s be honest the entire country of Laos is pretty mysterious to most people. Aside from once being a part of French Indo-China and then an unwilling participant in the Vietnam War I know little this small land-locked country. So I was quite excited to hear about the archaeological research going on by the University of Melbourne and the Australian National University along with the Laos Department of Heritage in the northern part of the country.

The plain of jars is actually a series of eleven sites where massive containers carved from sandstone are spread haphazardly across the landscape. Site 1, the largest location contains over 400 of these jars many of which are 2 meters across. Rather than being used for storage these jars were used for mortuary purposes where a deceased person would be placed in a jar and exposed to the elements. Carrion birds and other wildlife would consume the flesh and after a month or so, when only the bones remained they would be removed and placed in a more permanent, usually family based internment.

This form of funeral practice was actually very common in ancient societies. The longbarrows in southern England have been found to contain the bones of hundreds of individuals stacked together. There are even cases where the skulls of the dead were placed together in one chamber of the barrow while the other bones were placed in adjacent chambers.

The best theory for how the stone jars of Laos were employed follows much the same idea but there’s a problem. Chemical analysis of the soil beneath several of the jars indicates that they were placed in their current locations somewhere between 730 to 1350 BCE, around 3,000 years ago. However carbon-14 dating of some human remains buried near the jars give a much younger age of 800 to 1400 CE. Is it possible that the stone jars were used over such a long period of time? Or did a second, much later culture make use of the ancient jars that their distant ancestors had originally erected.

At least researchers have managed to identify where the stone for the jars came from. Chemical test have revealed that the stone came from a quarry just 8 km away. However, whether the stones were brought to the plain and then carved or carved first and then brought to the plain is unknown, as is the method used to move the stones, some of which weigh several tonnes.

We humans spread out across the face of the Earth thousands of years ago and so its not surprising that even the most isolated and little known parts of our world can still provide some archaeological mysteries worth studying.