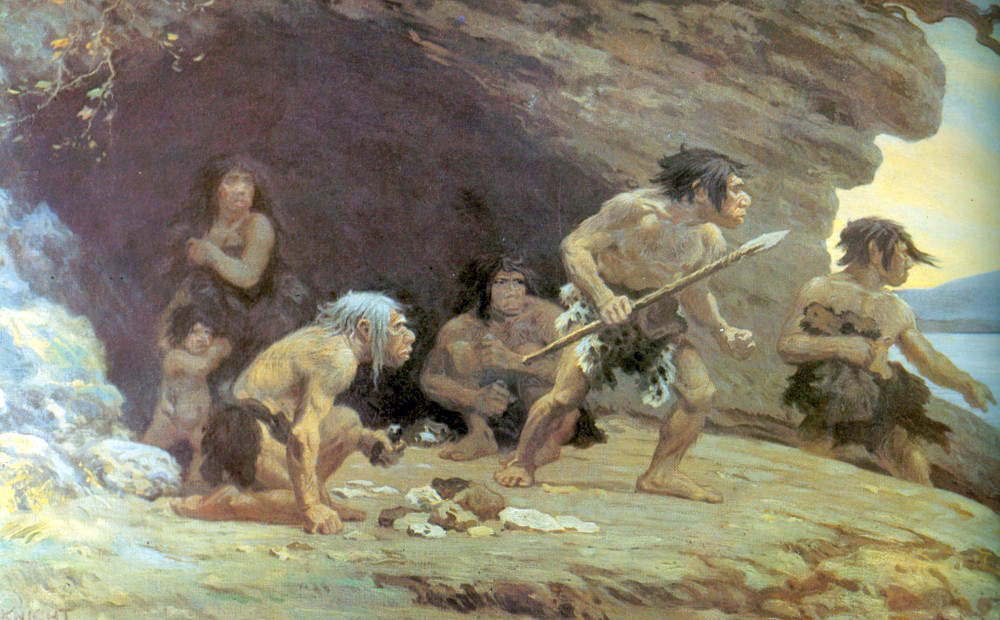

Our Stone Age ancestors, often dismissively referred to as ‘Cave Men’ are usually portrayed in movies and TV as being hardly more intelligent than the animals they hunted, or were hunted by. Little by little however archaeologists are uncovering evidence that Stone Age peoples were capable of flashes of genius in solving the problems they faced despite their lack of resources or tools.

Finding food is of course the biggest problem any animal faces and a large part of the success of our species, Homo sapiens is the wide variety of different kinds of food we eat, and that includes seafood. Think about it, what are we, an ape scarcely out of the jungle trees doing eating not only fish but clams and mussels, squid and even whale meat.

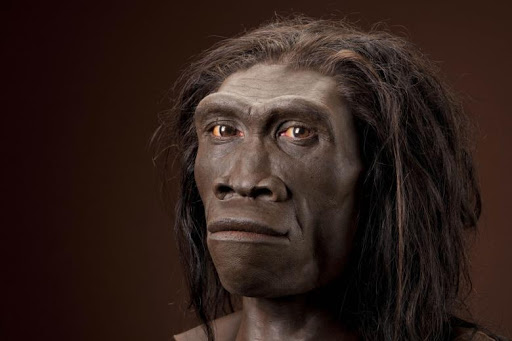

Over the last several decades anthropologists have even developed the hypothesis that it was learning how to make use of the food resources they found along the coast of West Africa that spurred a small population of Homo erectus to become H sapiens. There has even been speculation that the brain boosting fatty acids in the seafood those H erectus ate might have contributed to the growth of the larger brains of their descendants, that’s us.

Nice idea, but there’s new evidence coming from the field that is starting to show that other species of humans were also learning how to feast off of the bounty of the sea. I’m talking about our cousins the Neanderthals in Europe as much as 106,000 years ago.

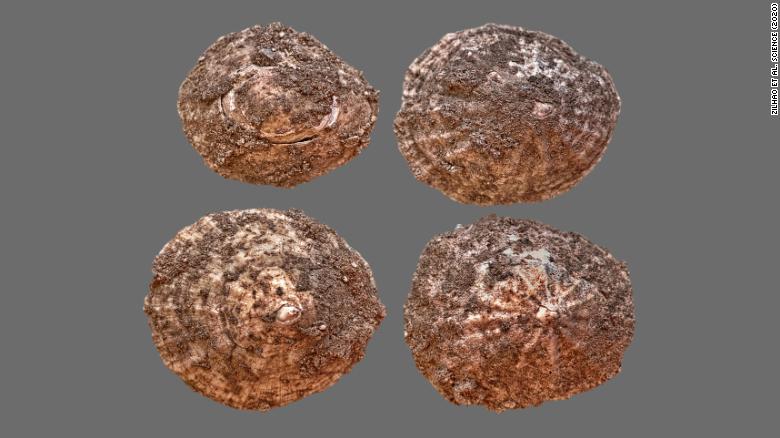

The new evidence comes from a cave site along the southern coast of Portugal at Figueira Brava near the town of Setubal. The interior of the cave has been excavated by a team of archaeologists led by Doctor Joăo Zilhăo from the University of Barcelona in Spain.

Those excavations have unearthed the bones and other indigestible remains of the animals that the Neanderthals were eating. Those remains clearly show that the Neanderthals were not only hunting the local land fauna of deer, goats, ancient cattle and even horses but were also catching and consuming large amounts mussels, crabs and such fish as eels and sharks! Even the bones of sea mammals like seals and dolphins were discovered in the garbage piles left by the Neanderthals. In fact Doctor Zilhăo and his team estimate that just about half of the diet of the inhabitants of Figueira Brava was in fact seafood.

So it seems as if our direct ancestors were not the only humans smart enough to realize the enormous benefits to be gained from dinning off of seafood.

Another recent discovery that also demonstrates the intelligence of Neanderthals is the unearthing of the earliest known piece of string from a site in Abri du Maras in southern France. According to the study co-authored by Marie-Hĕlĕne Moncel, Director of Research of the French Nation Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) the string fragment is dated to between 41,000 and 52,000 years ago. Composed of fibers from the inner bark of a conifer tree the section measures 6.2mm in length by 0.5mm in maximum width.

The string fragment is more than just a few fibers twisted together however. In fact the fragment consists of three separate twisted cords that have been interwoven together, indicating a considerable level of experience in textile production. But more than that the fragment also indicates a considerable knowledge of available natural resources since the fibers come from the inner part of the bark of a tree that, according to botanists, is best obtained during the spring or early summer.

The discovery of this single strand of cord opens up the possibility that Neanderthals may have made extensive use of textiles, perhaps to manufacture bags, nets, ropes, mats or perhaps even cloth? In any case this, oldest piece of string provides further evidence that Neanderthals were anything but brutish animals.

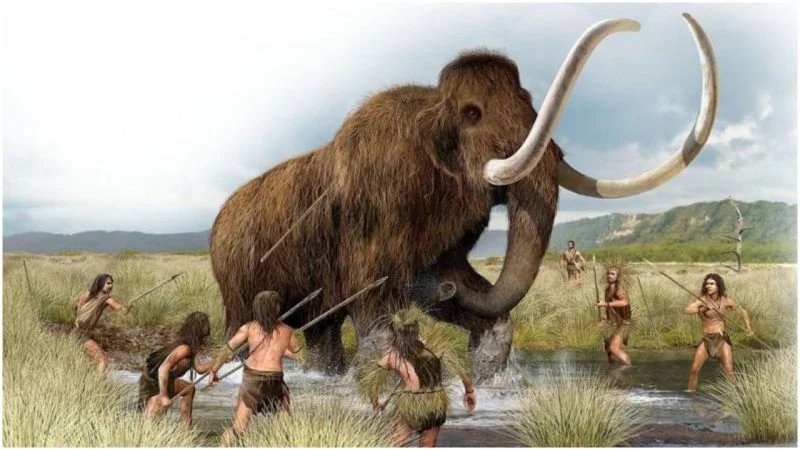

Moving a bit forward in time, to about 25,000 years ago we begin to see the first evidence for actual construction projects by human beings. Some of the most interesting sites come the fertile steppes of Russia south east of Moscow. Here Stone Age hunter-gatherers lived off of one of the largest and most dangerous animals ever pursued by humans, woolly mammoths.

We know that our ancestors hunted those ice age relatives of elephants because they had the curious habit of building circular walls out of the bones of the mammoths they killed. In a paper published in the journal Antiquity a team led by Alexander Dudin of the Kostenki Museum-Preserve describes the latest, and largest of these mammoth bone structures. Unearthed about 500 kilometers south of Moscow at a site known as Kostenki 11, the ring measures more than 12 meters across and was made from the bones of at least 60 of the huge beasts.

Because the other mammoth bone structures found across Eastern Europe are smaller than the new one at Kostenki scientists had speculated that the circular walls had once possessed roofs and were used as shelters by the people who made them. At 12 meters across however the mammoth bone circle at Kostenki is too large to be easily roofed in, leaving the researchers to think of some other possible usage for the structure.

Whatever purpose the hunter-gatherers may have had when they built the structures like Kostenki the fact that they did so clearly shows that like modern humans they felt the need to adapt their environment to suit their needs by building.

While it’s true that the earliest structures we humans built were probably used as dwelling places there is evidence that by 7000 years ago people were already learning how to build other types of structures as well. Archaeologists in the Czech Republic have recently discovered a well that they assert is the oldest known wooden structure.

In a study co-authored by Jaroslav Peška head of the Archaeological Centre in Olomouc the well is described as being built in a square shape some 80 cm to a side and 140 cm in height. Each corner of the square consisted of a vertical oaken tree trunk that had been grooved on its sides to allow flat wooden planks, also oak, to be inserted between them to make the square’s sides. This degree of woodworking ability particularly impressed the researchers. “The shape of the individual structural elements and tool marks preserved on their surfaces confirm sophisticated carpentry skills,” they wrote.

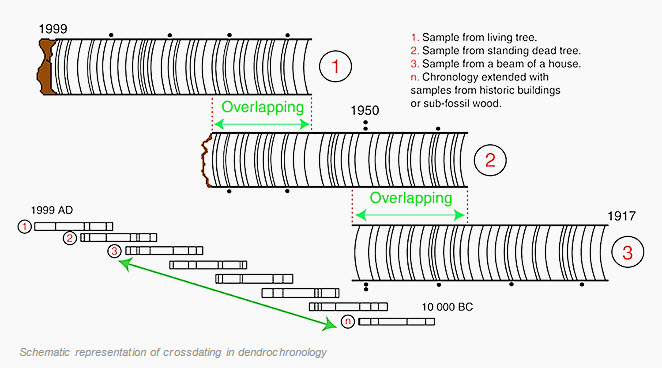

The technique that was used by the archaeologists to date their discovery is known as dendrochronology and is based on an analysis of the tree rings in the well’s wood. Over the past 50 years or so the tree rings in the wood found at many different archaeological sites across Eastern Europe, and from many different time periods, have been matched up, one to another in order to create a exact timeline that can now be used to very precisely date the wood unearthed at any ancient site in Eastern Europe. This same technique has also been developed in other areas of Europe and the different areas of North America and has been used to precisely date many archaeological sites. Using dendrochronology Doctor Peška and his colleagues have succeeded in dating the year that the trees were felled to either 5255 or 5256 BCE.

As different as these three archaeological discoveries are, each in its own way demonstrates that, for all of their primitive tools and crude materials our ancestors nevertheless were able to think up clever solutions to the problems they faced in their daily lives. In fact think about it, if they hadn’t been so bright, we’d still be living in caves ourselves wouldn’t we!