We humans like to think of ourselves as being special, not just more intelligent than ‘the animals’, but a higher sort of intelligence. In fact we used to insist that anytime an animal showed something resembling conscious thought we’d say that it was really just behaving by ‘instinct’, not intelligence.

That way of thinking has been pretty much tossed into the dustbin of science as naturalists have studied the many different species of animals who use tools, those who can communicate in some pretty sophisticated ways and whose problem solving skills can almost seem to rival ours in some ways. The list of these, intelligent species is quite long and getting longer everyday. Not just dolphins and chimpanzees but also dogs, elephants and squirrels not to mention other animals like ravens, parrots and even octopi. So let’s be honest, animals in general can be quite intelligent, each in their own way!

At least it’s only animals that show intelligence right? Plants don’t have anything like a brain. In fact plants don’t even move unless the wind blows on their leaves so how could you even tell if plants had anything like intelligence.

Actually of course plants do move, a sunflower will follow Sun across the sky each day and if you’ve ever had to keep ivy from twisting its way up a wall or tree trunk you’d know that plants can grow in a manner that displays a great deal of purpose if not intelligence. There is in fact growing evidence that plants are aware of their environment and can react to stimuli in ways that can be described as intelligent.

Take the Venus flytrap for example. Each individual trap has two hair like sensors that ‘tell’ the plant when something is in the trap. However in order to keep the trap from closing on a piece of a leaf or dirt it’s only when an insect triggers both hair sensors that the trap snaps shut. That’s certainly more awareness and intelligence than plants are generally given credit for.

Now consider a few experiments that have been conducted by Doctor Katja Tielbörger of the University of Tübingen in Germany. Working with the plant Creepy Cinquefoil (Potentilla reptans) Dr. Tielbörger used strips of green coloured cellophane to simulate competing plants. In one setup the competing plants were low vegetation that surrounded the Cinquefoil test plant. The Cinquefoil responded by shooting upward in order to get above the competition. In a second test the competing plant was very tall, hanging over the Cinquefoil. The Cinquefoil responded by growing outward to get away from its competition. Finally, the competing plants completely encased the Cinquefoil so that only bits and pieces of light could get through. The Cinquefoil responded by staying small but growing large leaves in order to catch every bit of light possible.

If you think that maybe those experiments only demonstrate that plants have evolved mechanisms that allow them to grow towards the light then consider this second experiment that Dr. Tielbörger performed with a different plant, Mimosa pudica, also known as the sensitive plant. M pudica and its relatives are fern plants that are known for their habit of closing up their leaves during the night. M pudica goes a bit further however because it will also close up its leaves when they are grabbed or even roughly brushed against. This behavior makes M pudica an excellent test subject for experiments in plant reaction to stimuli.

The experiment that Dr. Tielbörger conducted was this; whenever she turned on a bright light near an M pudica plant she would then puncture several of the plant’s leaves with a sharp poker. This damage caused the rest of the plant’s leaves to immediately close up. Doing this continuously for a month Dr. Tielbörger then discovered that the plant’s leaves began to close up as soon as she turned on the light and before she began to injure the leaves. The plant had learned to associate the light with the damage caused by the punctures and reacted in a fashion that can only be considered ‘learned’.

But how can plants learn anything, they don’t have anything like a brain. They don’t even have any kind of a nervous system that would allow them to react to stimuli the way an animal would. Well now a study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has uncovered one mechanism by which plants may be able to communicate different kinds and different levels of stress throughout their bodies.

Biochemists have known for several years that plant cells use the chemical hydrogen peroxide as a signal to induce production of chemicals known as secondary metabolites that help a cell repair damage to its structure. Some of these chemicals can also produce disagreeable flavours that help the plant to fend off predators. The way in which entire plants use hydrogen peroxide to communicate stress levels between cells has been more elusive however.

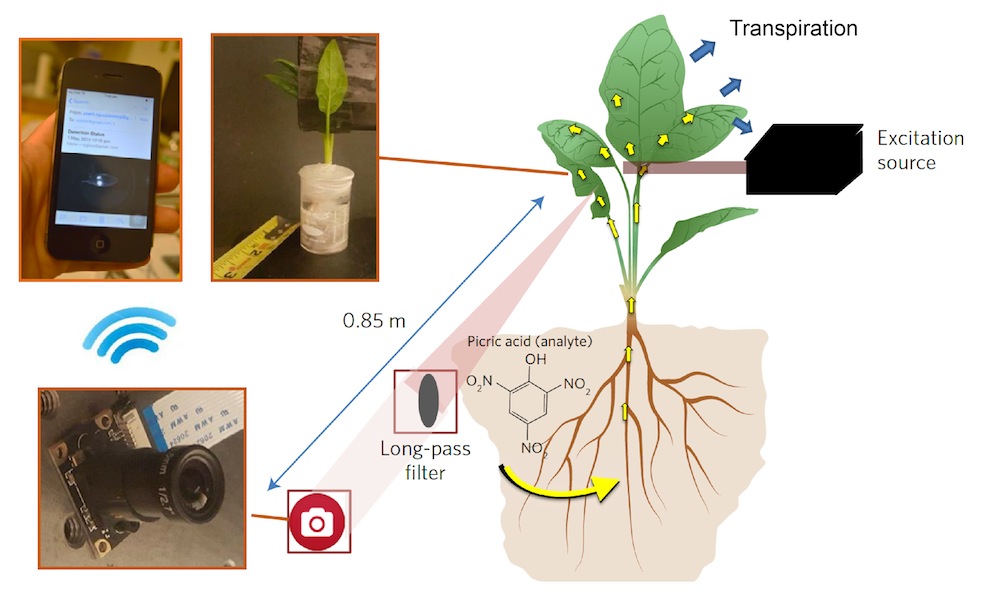

In a paper in the journal Nature Plants senior author Michael Strano, Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT, has detailed how he and his team succeeded in inserting sensors made of carbon-nanotubes into plant leaves and stems into order to detect and measure the flow of hydrogen peroxide throughout the plant.

So far the chemists have used their technique on eight different plant species including spinach, arugula and strawberry and plan to try it on other species going forward. These new sensors could give biologists their first glimpse into the ‘nervous system’ of plants, which could lead to a better understanding of plant intelligence.

Simply put, intelligence is nothing more than an awareness of your environment and reacting to it. When you look at it that way intelligence is pretty much just a part of being alive.